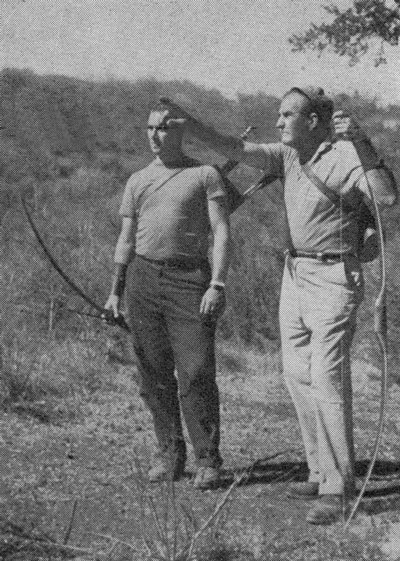

Since the age of six, Bob Swinehart had been daydreaming about bowhunting in Africa. By the time he’d reached adulthood and could make good on that childhood fantasy, he had become personal friends with a mentor who had plenty of experience hunting there—a man named Howard Hill.

“As a youngster,” Swinehart writes, “I never missed a Howard Hill short subject film in the local theater, even if I had to sit through one of those ‘lousy’ love pictures with an older brother or sister. While other kids raved about their baseball heroes, Babe Ruth or Joe DiMaggio, or boxer Joe Louis, I talked up Howard Hill, the world’s greatest archer—then and still.

Swinehart set out on his archery career as soon as he was old enough to “cut off a hickory limb and tie some binder twine to it.” His arrows were long, stiff Pennsylvania meadow weeds that had hard, pointed roots. They flew “amazingly accurately”—at least for short distances.

After college and a stint in the army, Swinehart finally met his hero, Howard Hill. In fact, he not only met him, but had the opportunity to work with him and become personal friends as well.

“From doing shows together with his Africa film TEMBO, living together, hunting together, much bow lore was passed on to me from Howard, and many true tales of Africa—its game and people,” he writes. “It was during the first year of our acquaintance that I knew that I’d definitely be going to Africa to hunt the likes of elephant and rhino—someday, somehow.”

Swinehart was a careful planner and spent considerable time learning all he could about such an undertaking. As he did, he became well aware of its many challenges.

“History records only a handful of archers that have hunted dangerous African game with conventional bows and arrows. The well-known Fred Bear, hunting in Africa several years ago, was unable to kill any of the Big Five, and evidently it was a grueling ordeal. The reports I had up until a couple of months ago were that he never intended to return.” [Author’s note: The “reports” were incorrect. Although Bear’s first safari in 1955 was unproductive, a second trip in 1964 resulted in his taking an elephant, while a lion and cape buffalo were taken on a third safari the following year.]

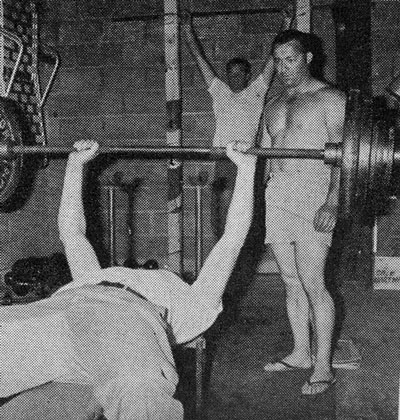

In the months leading up to his departure for the Dark Continent, Swinehart began to get himself in shape for the challenges ahead.

In the months leading up to his departure for the Dark Continent, Swinehart began to get himself in shape for the challenges ahead.

“Physical fitness is a must,” he believed. “No matter how brave or accurate you might be, elephants are not killed with 40 pound bows and light arrows. Conceivably a 65 pound bow could do in an elephant, but I feel the proper weight is 90 and up.”

Aside from the physical strength to handle a stout bow, the writer advises African bowhunters to condition themselves in other ways as well.

“Elephant hunting can be very arduous, covering a great many miles of rough terrain. Unless a prospective bowhunting safarist is constantly in top shape, he’d better begin a gradual training program a year in advance.“ He also mentions conditioning the mind. “I cannot stress the mental aspect enough. If the hunter is not totally prepared mentally and physically for the moment of truth, that frightening feeling of stalking within 20 yards of a monstrous African bull elephant, which can tower twelve feet to the shoulder, one is very likely to go completely to pieces.”

To help him anticipate the unexpected, Swinehart read everything he found on the subject of safari hunting. Two of the books he mentions as the best sources were Safari Today by Robert Lee and John Taylor’s Pondora. In this latter book, he states that the author “explodes a lot of the hogwash and unfounded theories on the behavior of the Big Five.”

During this period of preparation Swinehart also kept in touch with Hill, who, he states, “knows how to bowhunt Africa better than any man alive.” In every letter Hill would caution him not to take unnecessary risks—the downfall of “young guys” who think that because they are agile they are invincible enough to avoid trouble. Some of Hill’s admonishments:

“African trip most dangerous. Be careful.”

”One mistake and the hunt will be over—for keeps.”

“Do Not leave white hunter (back up with a rifle) at ANY TIME, and go off on own—UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.”

“Beasts are deadly and tough, and if they charge can only be stopped cold by a well-placed bullet.”

“I took a few chances and had a good deal of luck.”

“Any animal in Africa can kill you. Remember that!”

Hill believed that the elephant was the most dangerous of the five, referring to Jumbo as a “massive bulk of T,T & T—trunk, tusks or trample.” Swinehart agreed, but speculated that the leopard would be the most difficult to kill with an arrow.

Accompanying him on the trip would be a number of tempered bamboo bows custom made for him in a variety of draw weights. “…birds, rabbits, reptiles and other varmints are easily handled with a regular bow pulling 60 pounds,” he tells us. “For the likes of lion and leopard, or fish (because of heavy solid glass arrow), a 70 pound bow is plenty. Rhino, Cape buffalo or crocs should be shot with something a mite heavier, says Howard, about a 90 pounder. And as for elephant, the more power the better in order to deeply penetrate the lungs. I’ll probably use my 100 or 110.”

Accompanying him on the trip would be a number of tempered bamboo bows custom made for him in a variety of draw weights. “…birds, rabbits, reptiles and other varmints are easily handled with a regular bow pulling 60 pounds,” he tells us. “For the likes of lion and leopard, or fish (because of heavy solid glass arrow), a 70 pound bow is plenty. Rhino, Cape buffalo or crocs should be shot with something a mite heavier, says Howard, about a 90 pounder. And as for elephant, the more power the better in order to deeply penetrate the lungs. I’ll probably use my 100 or 110.”

The special broadheads he had prepared for elephant hunting were patterned after the Howard Hill head (which Hill had used to puncture his pachyderm), and were handmade by a local machinist. For the arrows, Swinehart relied on well-known arrow-maker Carson Kemp, who turned out 17 dozen for the trip.

“Most are Micro-Flight fiberglass,” he tells us. “Glass has several advantages. It doesn’t warp or bend or break easily, and has great adaptability in spine. In a pinch I can easily use the Number 9’s (intended for the 70 pound bow) from either a 60 or 80 pound bow, and the flight is quite satisfactory, particularly at close range.“

The bows in the heavier weights posed a problem. Due to some sightseeing stops along the way, it would be a good two weeks between the time that Swinehart left the States and the beginning of his hunt. During that period he had to come up with a way of keeping his muscles toned and fingers calloused so he could remain in the top shape required to handle the elephant bows. A call to another friend in the archery business, Ben Pearson, solved the problem. The company had a heavyweight takedown fiberglass bow that Swinehart could pack with his personal luggage. The bow could be paired with rubber-tipped arrows for some shooting into pillows in various hotel rooms along the way. Swinehart also planned on doing isometric exercise to keep his muscles toned.

And, of course, there were 40 pounds of pretzels to pack. Having grown up in Pennsylvania pretzel country, Swinehart admitted an addiction to them. Thus prepared, Robert Swinehart would set out for his first safari.

“The visitor who gazes upon an African moon will return,” they say, and so it was with Bob Swinehart. After his initial trip he went on to return seven more times, eventually becoming the first man to take all of Africa’s Big Five with his longbows. He recounts some of his adventures in his book Sagittarius—one of bowhunting’s classics, which, unfortunately, has been out of print for many years.

The so-called “Big Five” are the elephant, Cape buffalo, rhino, lion and leopard. Each presents unique challenges, especially with a bow and arrow. Any of them can kill you in a heartbeat, but Swinehart agreed with his mentor, Hill, that the honor of the “most dangerous” should go not to the King of the Jungle, the lion, but to the elephant.

“Try to visualize a dark mass,” he writes, “12 feet high by 12 feet wide (with ears outspread); two long white tusks protruding like swords, sometimes weighing over 100 pounds each, and feet 24 inches from toe to heel stomping the earth like pile drivers, carrying a body that may exceed 14,000 pounds, smashing trees to the ground as though they were toothpicks. That’s the African giant, a living dynamo!”

He maintains that there is no question that the elephant is the most difficult animal for the archer to bring down, explaining that not only does it have skin an inch and a quarter thick, but it is also the toughest of any beast on the continent. “It resists cutting like pressed cardboard, and dulls a knife within a few strokes,” he tells us. “Driving an arrow through a barrier like this is probably the ultimate test for the archer.”

His guide found a big bull, and after a “stalk”—done at a fast trot which continued for several hours—the opportunity to strike finally came. When he had closed the gap to 22 yards, Swinehart burst from cover in plain view of the pachyderm.

“My sudden appearance so surprised him, he made no attempt to charge—rather put himself into high gear to elude me. But the arrow had been released at his quartering broadside the instant I had bolted into his view. The heavy shaft buried to the feathers.”

Swinehart also collected at least four Cape buffalo with his bow. Ironically, he reports that his closest call with a buff came while he was carrying a gun as he and his guide were collecting meat for their camp. Swinehart was handed a .375 H&H Magnum rifle and instructed to shoot a large mbogo that they had spotted. He made a good shot that dropped the big bovine in its tracks, but as they approached cautiously to within 20 yards it suddenly came back to life and charged. Swinehart fired again, hitting the buff squarely, and as he jumped aside his guide put another round into it. The animal then took a swipe at the Land Rover, nearly knocking several natives out of it before turning around for another go at the two white hunters. It zeroed in on Swinehart again while his guide and a gun-bearer poured fire into it, and finally succumbed to a shot from Swinehart’s weapon, taken with the muzzle nearly touching the animal. Amazingly, Swinehart refers to this heart-pounding incident only as “one” of his closest scrapes.

On the same safari, he killed another buff with his bow at a range of 25 yards. This time the animal reacted as if it had merely been stung by a thorn or an insect, ran a way, and then fell over dead. The contrast between the bow kill and that with a large caliber rifle makes an interesting comparison.

The third member of the Big Five, the rhino, also didn’t present any problems, even though someone likened his attempt to shoot one to “downing a battleship with a bow and arrow.” Although Swinehart downplayed the comparison, he does describe the beast as an “ill-tempered monstrosity of nature.” This seemingly ungainly monstrosity, however, can run at speeds of 35 mph and can turn on a dime, and “should he miss you the first time with the wide sweep of his horn, he won’t the second.” Bagging this massive beast was necessary to complete his Big Five quest, so Swinehart set out with his 90# bamboo longbow and 1200 grain arrows with metal nocks and Hill broadheads.

His first encounter resulted in a charge, but his guide fired a pair of rounds out of his .475 just in front of the animal. Fortunately, the noise and kicked-up dust caused the animal to veer off and keep going.

The following day they came across another rhino, which had remained invisible until they were within 20 yards. Although it hadn’t winded them, it evidently sensed the hunters and trotted off. They continued the stalk, and when they had closed to 18 yards Swinehart released an arrow. At the same instant, however, the rhino turned toward him and the arrow glanced off its chin. Swineheart fired another arrow seconds later, which went through its lungs. After a short hike, the three-ton “battleship” was found to have sunk—stone dead to the ground with a single arrow.

The leopard, Swinehart’s personal nemesis, proved to be the hardest of all to shoot. It required numerous tedious, cramped sessions in a tree blind, and when the shot finally did come, Swinehart had to fire the fatal arrow at nothing more than a silhouette against a nearly dark sky.

The opportunity to bag a lion, the most difficult animal to get a shot at, didn’t come until a fourth safari. After a lot of fruitless searching for a cat in the open, a flock of circling vultures led the party to a lion feeding on a kill in dense cover. They spotted the cat at 35 yards, but it only offered a frontal shot. Swinehart nonetheless took it, and buried the shaft in the lion’s chest. Although the shot was probably mortal, a second arrow taken at 25 yards for insurance finished it just as the lion prepared a last charge.

When he returned home after finally completing his quest, Swinehart’s accomplishment was celebrated in numerous newspapers and magazines, and he was in great demand for public lectures. He even appeared in Ripley’s Believe it or Not as the man who had killed a rhino with a stick bow.

When he returned home after finally completing his quest, Swinehart’s accomplishment was celebrated in numerous newspapers and magazines, and he was in great demand for public lectures. He even appeared in Ripley’s Believe it or Not as the man who had killed a rhino with a stick bow.

Although he was a protégée of Hill, even before his trip to Africa Bob Swinehart had become a respected bowhunter in his own right. Hill wrote of him:

“During my many years of hunting with the bow and arrow, I have covered different parts of the world and have hunted with many archers. Of these bowhunters I am convinced that Bob Swinehart is the best big game hunter I have had the pleasure of being with on the trail and in the bush.

“He not only is an extremely good shot with the bow, but in addition has a great deal of patience, is a fine tracker and possesses great courage… Also for a man his size—weight 170 and height 5 feet 10 inches—his strength is prodigious. He can handle bows pulling over 100 pounds.

“When this young man set out to down Africa’s Big Five with bow and arrow—something he had been dreaming of since a boy—I was confident that he would accomplish the task, providing he did not get himself killed first. My only criticism of him was that he took too many risks.”

Formidable hazaña, notable arte de manejar un arma antigua, que increíblemente tiene una energía apenas igual a la de una bala 38 special, disparada desde un ñato SW10, nos muestra la eficiencia de una flecha del pasado. Se deberían haber conservado más elementos de información al respecto, ya que constituyen un acervo de la Historia del Hombre, realizado por un dotado sin dudas, que nos admira.-