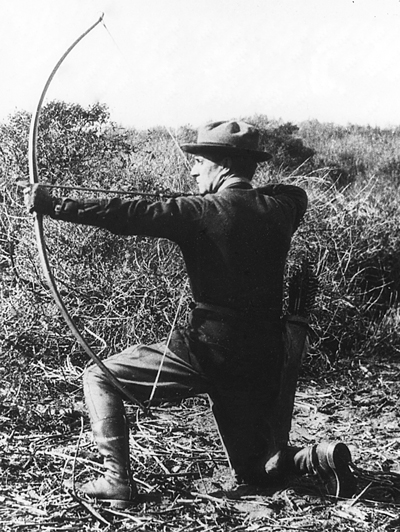

One man clearly stands out when you think back to the advent of modern bowhunting in the United States—Saxton T. Pope. What Maurice Thompson started in the late 1800s, Pope took to the next level in the 1920s.

Saxton Temple Pope was born at Fort Stockton, Texas, on September 4, 1875. His father, Benjamin Franklin Pope, was a surgeon in the army, a career that the younger Pope would follow later in life.

Saxton’s elementary education was acquired haphazardly, since his early years were spent moving from one camp to another as his father’s garrison changed its duty station. His companions were a strange mix of Indians and cowboys, among other characters. Because of his lifestyle, he developed an independent quality that would shape his entire life. He also loved to hunt, fish, swim, and shoot guns. His was a unique childhood.

Even though he spent much of his youth on the move, he eventually graduated in 1899 with honors, receiving a degree in medicine from the University o

“In the joy of hunting is intimately woven the love of the great outdoors.”

Saxton T. Pope, Hunting with the Bow & Arrow, 1923

f California. After his internship, he moved to Watsonville, California, south of San Francisco, to set up his practice and married another doctor, Emma Wightman. The Pope’s raised four children: Saxton Jr., Elizabeth, Virginia, and Willard Lee Pope.

Saxton spent about 12 years in Watsonville before he accepted a job as Instructor of Surgery at the University of California Medical School in 1912. Within a few years, he was promoted to Assistant Professor, and then to Clinical Professor of Surgery. Even though Dr. Pope was active in medical organizations and conducted intensive instruction for hospital units during the war, he still found time to publish over 32 scientific papers.

That same year he met Ishi, who was living next to the Medical School in the Museum. Ishi and Pope became friends, and Pope learned how to make and shoot Indian bows and arrows from Ishi, who called the doctor “Popey.” In return, Pope saw to Ishi’s needs, whether medical or cultural. Many times, Ishi came to the Pope household for dinner and was always a man of good manners, never looking or speaking to Mrs. Pope or any other woman, as that was considered rude in his culture. Years later, Pope’s daughter, Virginia Evans, said that Ishi was quite jovial during his visits to their home. 1

Pope met William “Chief” Compton and Art Young in 1915. The three of them and Ishi soon became friends who spent their days making archery tackle, shooting at the range on the University grounds, and hunting both big and small game as far away as Humboldt County in northern California. Then in 1916, Ishi died from pulmonary tuberculosis. The three remaining archers continued to pursue their love of bowhunting for many more years.

Describing hunting with Ishi, Pope said, “Although Ishi took me on many deer hunts and we had several shots at deer, owing to the distance or the fall of the ground or obstructing trees, we registered nothing better than encouraging misses. He was undoubtedly hampered by the presence of a novice, and unduly hastened by the white man’s lack of time. His early death prevented our ultimate achievement in this matter, so it was only after he had gone to the Happy Hunting Grounds that I, profited by his teachings, killed my first deer with a bow.” 2

Saxton Pope and Art Young spent several years hunting northern California, where they succeeded in taking deer, bear, cougar, and elk. Most notable was their trip into Yellowstone National Park. In the fall of 1919, after receiving a permit to enter Yellowstone in an attempt to secure several bears for the California Academy of Sciences museum with their longbows, the two men started to organize their campaign for the following spring, with Ned Frost of Cody, Wyoming, as their guide, a man known to be the best grizzly hunter in America.

The following May, Pope, Young, and Frost, together with Pope’s brother, G.D. Pope of Detroit, and Pope’s friend, Judge Henry Hulbert, also of Detroit, entered the park on their quest. The bowhunters had shipped ahead their archery equipment consisting of two bows apiece and, “…one hundred and forty-four broad-heads, the finest assembly of bows and arrows since the battle of Crecy.” 3 One of Young’s bows was 85 pounds, the other a proven veteran of many hunts, Old Grizzly, that drew at 75 pounds. Pope had brought two bows, both 75 pounds, including his favorite, Old Horrible, a bow that was sweet to shoot and hit hard, as well as Bear Slayer, a fine-grained but crooked bow that he had used to take the duo’s first black bear in California.

Over the course of the spring the group looked for grizzlies, finding them scarce until the elk moved back into the park and began to calve. Their first encounter ended up with a ragged sow and a fine younger bear. As the days turned into weeks, the group began to dissipate as each member had to return to work and civilization. In the end, Frost packed both Pope and Young to a new camp, stocked them with enough provisions for a few more weeks, and left to guide other hunters in Wyoming.

For a little over a week the two bowhunters had been seeing a magnificent bear they called the Monarch of the Mountain. They decided to set an ambush for the brute in a perch of rocks above a trail the bear had been using. After several nights and close encounters, their opportunity came to fulfill the museum’s request.

The two men headed to their blind about an hour before midnight, with the moon near full. (Of course, at that time there were no laws prohibiting hunting at night.) A few hours later, a beautiful sow and her family made their way up the trail. When they were in range, Pope gave the signal and they loosed their shafts at the cubs, hitting one apiece. At the hits the big sow roared and searched for the cause of the disturbance. She saw the two men and started to charge. At that very moment the big monarch appeared, and now there were five bears in front of the men.

Pope whispered to Young to shoot the big boar, while he sent an arrow deep into the sow as she charged, turning her sideways where she roared, stumbled, and fell within sight. The old monarch was growling and pacing back and forth not more than 65 yards away as Young sent three arrows his way. Pope discharged two at the beast himself. (Recall that modern standards of fair chase regarding sows with cubs and shooting distances had not yet evolved.)

After this exciting encounter they skinned the sow by flashlight and then went and recovered one of the cubs at daybreak. The other cub was not to be found. Retrieving their arrows, they found that one of Art’s arrows was missing. They followed the direction the boar had run and then found blood. After an exhaustive search that took most of the day, they came upon the big bear where he had died and fallen. “There lay the largest grizzly bear in Wyoming…One great arrow had killed him.” 4

Five years later the two men accepted the challenge of hunting Africa with the goal of securing the dreaded African lion by means of their primitive weapons. In February 1925, they set sail, arriving on April 6th. They spent the next four months traveling and hunting across what is now Kenya and Uganda, taking several specimens of African game including wildebeest, eland, waterbuck, kongoni, reedbuck, and Thompson’s gazelle, as well as geese, rabbits, hyrax and guinea hens, securing enough meat to feed the camp for the entire trip.

They also shot several lions, but many had to be finished off at close quarters with a rifle and all of them were taken while being backed up with a rifleman at the ready. This bothered the two bowhunters. “No matter how many lions we shoot with the bow, somebody is always taking the joy out of the jungle by saying, ‘Yes, but you couldn’t do it without being backed up by the big boys with the guns!’ ” 5 But this would change with one lion in particular.

It was August 18th, 1925. Pope and Young had found an old boma, or blind, that had been built a year earlier by their professional hunter, Leslie Simpson. A kongoni was shot and drug all over the country, finally being wired to a tree 15 yards in front of the boma. The first night they stayed in camp, but a lion had come and eaten part of the bait leaving behind a large track. The following evening the two men sat in the blind, thinking of the absurdity of what they were doing, waiting for the lion to return. “Sitting in a clump of thin, rotten thorns, waiting for a lion to come up and mess about you, is an emotional novelty act. You sit there, holding your breath, hoping that he does come, and fingering your arrow heads and bow string, wondering if you have done the right thing in leaving your nice warm bed and crawling into this miserable bunch of little sticks, so close to him.” 6

The sun had set, and a cool breeze blew as they lay back in the sweet jungle grass and waited. But the lion didn’t wait long: a grunt came from the dark outside the boma, but the men could not hear its footsteps. The two bowhunters sat in the back of the boma, trying to arrest their heavy breathing, as the lion made its way to the bait and finally, once it felt the situation safe, began licking and tearing at the kongoni. Art stole a glance from the blind, saw the lion lying broadside, and motioned Pope forward. They studied the beast, braced their bows, nocked arrows, and settled themselves to shoot. With a whispered count, they let their shafts fly.

“There was a grunting roar and in one bound the lion stood before the aperture in our blind, his mane standing erect, glaring at us with green eyes like two X-ray tubes. He was so near I could have touched him with my bow. I saw the shadowed outline of a feathered shaft deep in his side.” 7 The lion took off into the night. They heard him stumble and fall, biting at the shaft protruding from his side. He gave a long, low moan, then it was quiet.

The men stayed in the boma until daylight whereupon they found the lion, very much dead, facing toward them as if to defend himself. Young’s arrow was buried to the feathers, through the chest above the heart. Death was quick. “After being hit, he had not lived 15 seconds. One arrow had killed him…There lay the finest maned lion in Africa killed with the bow and arrow. It was a wonderful sight!” 8 The adventures of Saxton Pope and Art Young in Africa are well documented in Pope’s book, The Adventurous Bowmen. The famed hunter and author Stewart Edward White also relates these stories from a different perspective in his book, Lions in the Path.

Unfortunately, the African safari was to be the last bowhunt Saxton Pope and Art Young would enjoy together. Soon after Pope returned to California, he contracted pneumonia and died in 1926.

Saxton Pope was not only a pioneer in archery and bowhunting, but an excellent writer who has left us two exceptional volumes about his escapades with the bow and arrow, as well as several essays and a complete history of Ishi, the last truly traditional American Indian. All of us who hunt with the bow and arrow owe Saxton Pope a great debt of gratitude, for many consider his famous book Hunting with the Bow and Arrow the bible of present day bowhunting.

Leave A Comment