The wide-racked herd bull stood facing me at six yards, moaning, drooling, and mooing like an Angus. A string of slobber nearly reached the ground as he rocked back and forth. I knelt behind a three-foot spruce with my longbow, hoping for a shot opportunity on this last morning of a long season. I’d heard him bugle above in the timber as I was returning to my Jeep to pack up camp and head home. With one last ditch hope, I voice-bugled back at him, mimicking his call, and heard sticks popping as he galloped down the hill. He had pinpointed the source of the call and was searching for the challenging bull.

Plan your shooting windows in the timber. After a few moments this bull lost interest and walked past me at ten yards, presenting a perfect quartering away shot opportunity through the aspens.

I waited patiently with an arrow on the string, hoping he would slowly turn for the kind of quick shot opportunity that can only be made with a traditional bow. Instead, he did the next best thing and began to circle into the trees. As his eyes disappeared behind the first one I quickly drew my takedown longbow and laced an arrow through the boiler room. He lurched ahead for fifteen yards, stopped, then toppled over backward. My morning transformed from a long hike back to the truck while rehearsing shopworn excuses to disbelief and exhilaration.

Elk hunting is a pursuit made for traditional equipment. The terrain in which elk live, the willingness of bulls to come to a call, the tight shooting windows in the timber, and the ability of a traditional hunter to execute quick, accurate shots all combine to make elk the perfect quarry for our style of hunting. By using woodsmanship skills to craft close range shots and maximizing the advantages our equipment offers in these situations, the traditional hunter is presented with thrilling, in-your-face encounters that long-range modern equipment hunters will never experience.

Creating the Shot

The most important element is the crafting of the close opportunity. This often happens on the fly, as an elk is approaching. I start assessing shooting windows and opportunities to draw as soon as I think the elk is coming, and before he appears if I’m cold-calling. Failure to plan ahead for the shot cost me many elk early in my hunting career. I’d realize afterward that I should have shot, but was so caught up in excitement that I didn’t interpret the moment.

The willingness of bull elk to come to a call, and come very close, is what draws so many trad hunters to the challenge.

Many hunters try to stop an elk with a cow call, which sometimes works but often does not. Elk hear cows talking all the time during their daily lives. A better option is a sharp “bark” (with a mouth diaphragm) or, my favorite, a hard grunt made by sucking in air through my throat. They stop instantly, head behind a tree, and shooting windows open. I advise practicing this “stopping” trick when you’re shooting at home so that it’s natural at the moment of truth.

Creating the close shot is a skill unto itself. It helps to find a calling location where the bull must come into bow range to spot the source of the calls. If he gets to an opening and doesn’t see anything, he will generally hang-up and stare for a bit before losing interest and leaving. A portable decoy can help prevent this, but it’s not foolproof. Two hunters working together can be deadly, as the caller can sit behind and to the side of the shooter in a place where the bull must search for him in a thick patch of timber or over a rise or ridge top, while the shooter can hide in a position that offers multiple shooting lanes. Bulls like to follow trails when coming to a call, so the shooter should be a few yards downwind of a trail. The caller can also flash a decoy to draw the bull’s attention. When hunting alone, which I usually do, it’s not unusual to see antlers appear over a rise a few yards away if my plan works. When that happens, I hold still and wait for the bull to walk past or turn to look back behind. I’ve had many shot opportunities inside fifteen yards by doing this.

Ground blinds at waterholes and known crossings are great tools for close-range setups.

Calling techniques are a topic for an entire article, but simply put, you need to sound like elk, not necessarily like a “contest caller.” I’ve heard plenty of bad calling from live elk. If calling cold and nothing answers my locator bugle, I try to sound like a small herd that has moved into the area, maybe a couple of cows and a calf with a small bull. I pop sticks, break branches, drum with a stick on a log on the ground like hooves hitting it, adding cow-calf herd talk, occasional bull squeals, and a benign bugle or two. It’s a totally different strategy from the overhyped challenge type calling, and more natural in the elk woods. I often find a spot thirty to forty yards downwind and move there immediately after completing a calling sequence. I plan this ahead of time to catch silent bulls that may try to sneak in behind me.

Herd bulls will leave their harem and slip in to see who the new bunch is, as will satellite bulls. It may take a half hour, but they come, and many hunters lose patience and leave a calling location too soon. I once followed a big herd bull over the Continental Divide and down into a different drainage nearly a mile away to figure out who was bugling over there. He left his cows and silently walked the whole way, then returned to his cows as they made their way to the bedding timber. He never made a sound the entire time.

This bull “appeared” in the author’s calling-decoying setup at ten yards, bugling and setting off the feedback loops in his hearing aids. He waited for him to walk past, and when his head went behind a tree at seven yards, he quickly drew and shot.

With multiple hunters, a “triangle setup” can be deadly, with one caller on point and the other two off to the side and behind to catch the bull when he circles. All three coordinate calling, and if one stops, it usually means an elk is coming and the other two should continue with herd talk. This method can produce point-blank shooting opportunities if done right.

Ambush setups and ground blinds in saddles, along well-used trails and fence crossings and at waterholes and wallows can be deadly too, so long as the wind is right. Elk rarely follow the same path to reach the saddle or crossing, but the thermals are usually predictable early and late, so these funnels can be great for close-range morning and evening ambushes. Waterhole hunting in much of the West can be very tricky because the wind usually swirls in the afternoon when they come to drink, and they often come in from above. This means that even tree stands are iffy because the elk smell you when the rising thermal hits the slope. I know literally dozens of great waterholes and wallows where I hunt, but only a couple are suitable for sitting without being winded. I envy the folks with waterholes they can hunt all day during the early season.

We often build small ground blinds out of stacked logs and pine boughs in known ambush spots, and use them season after season. When elk are working up a slope or down a ridge, we can hurry to one and jump in, knowing our shooting lanes are clear ahead of time.

Running and gunning on the ground can be very effective, using the terrain to get ahead of a herd or shadow them until the herd bull makes a mistake. Bulls often don’t respond to calling when the herds are on the move, but they will cycle around the perimeter. The broken terrain in elk country allows a hunter to sneak ahead and plan a close-range ambush. The danger is in bumping a stray cow, which can set off a chain reaction and send the entire herd two drainages away.

Equipment

Traditional hunters hotly debate equipment choices for elk, and much of the discussion reaches an almost religious fervor. The internet forums are full of “experts” who have read something somewhere, possibly have killed an elk or two, and absolutely insist that a certain weight bow or arrow is imperative, a certain style of broadhead is the only acceptable one, FOC-this, KE-that, and anyone who doesn’t follow their advice is irresponsible, unethical, whatever. Polite, honest discussions are productive, and we can all learn from each other’s experiences. Disagreement is part of human nature. Hunters have been arguing about equipment for as long as humans have hunted. But when disagreement degenerates into vitriolic insults and bitter character attacks no one benefits, and inexperienced bowhunters with the most to learn are quickly turned off.

The author killed this great bull at twenty-two yards while hiding behind bushes near a waterhole. It was hot and the elk weren’t responding to calls, so he adapted his tactics and found a well-used waterhole with a cedar patch on one side that hid him well.

Rather than rolling around in that wallow, I’ll simply state that my partner, Tom Kelley, and I have killed dozens of elk with reflex/deflex longbows and recurves he built ranging from 52-57# draw weight, with arrow weights 450-500 grains.

Almost all of our sixty-seven archery elk have been taken with 125-grain multi-blade, replaceable blade broadheads on which we’ve stone-sharpened the Trocar-style tips to be cut-on-contact, and have touched up the blades out of the package. We shot aluminum shafts for many years, but switched to weighted small-diameter carbons and have been very pleased with the results. I have friends who have good success with woods, who have the patience to sort and spine them.

Before you jump up out of your chair and exclaim, “No, you MUST use a two-blade cut-on-contact (COC) head, with a 700-grain arrow, with at least 60# of draw weight because I read that on the internet!,” I’ll acknowledge there are advantages and disadvantages to any equipment choice. A two-blade broadhead is best for pure penetration, but can result in less tissue damage and a limited blood trail compared to a multi-edged wound. I’ve shot through an elk scapula with a four-blade head from a recurve on a steep downhill shot, and killed the bull quickly. A heavier arrow carries more momentum, but sacrifices trajectory. In the elk woods where virtually every shot is at an unknown distance, and where depth perception is affected by trees and terrain (and the size of elk), flatter trajectory means greater accuracy and less potential for error. The majority of misses and wounds I hear about from the super-heavy arrow hunters are from high or low shots.

I believe that the most important aspect of a setup, besides the ability to shoot the first arrow accurately at unknown distances under pressure, is having a perfectly tuned arrow to deliver maximum energy, tipped with a razor-sharp broadhead. I’m amazed at how many folks at shoots have poorly tuned or improperly spined arrows that wobble all the way downrange, yet seem to accept such performance as “normal.” A broadhead amplifies this problem. I politely mentioned it to a fellow once at a shoot, and he just shrugged and said, “That’s traditional archery.”

Likewise, when people show me their broadheads, many of the two-blade COC heads are alarmingly dull because the hunter doesn’t know how to properly sharpen them. A wobbly 700-grain arrow tipped with a dull broadhead is a compromised tool, yet many hunters justify it because they have the “proper” arrow weight and head style.

If you are accurate with a heavy arrow and bow combination with no warm-up at unknown distances after hiking three miles at altitude, by all means shoot it. Go with the heaviest bow-arrow combination you can shoot into an 8” pie plate with your first shot every time, and then promise to keep your shots within that range. If you like two-blade broadheads, learn to sharpen them to a razor edge. But remember that we are hunting big deer, not Cape buffalo, and a setup designed to kill a rhinoceros isn’t necessary for quick, clean kills on elk. The combination we’ve settled upon is a balance between maximum accuracy and shot placement at unknown distances, penetration, and killing potential.

Clothing

The author’s elk hat, crafted by his wife, held this bull while the author drew and shot. The elk hat is a great tool where safe and with no gun seasons in progress. Please use caution!

Wool is ready-made for elk hunting. The natural water repellency helps for those brief afternoon rainstorms. It is soft, quiet, and durable, and seems to absorb light rather than reflect it like some of the newer synthetics. Elk hunting in September can bring heat, wind, hail, and snow, all in the same day. It’s important to plan for any and all situations. Base layers of Merino wool beneath a light or heavy wool shirt, with a midweight wool pullover or jacket will get you through most situations. I also have a wool vest for those chilly mornings. A packable rain suit is a must, because an afternoon hailstorm can drop the temperature forty degrees in minutes and saturate everything. Camouflage is the least important element to consider. My favorite wool outer hunting outfit is a neutral gray, and seems to blend into the trees and forest.

Shot Placement

As with any animal, placement is crucial for recovery. Elk are big, with a large vital area. That’s the upside. The downside is that they are extremely tough and can lose a lot of blood before succumbing. A high double lung shot often leaves little or no blood trail. Don’t rely on the “kill zones” shown on 3-D targets, as they are highly misleading. Instead, study elk anatomy from charts available on the Internet and learn to pick a spot near where the top of the heart intersects with the lungs. That gives a good margin for error and results in a quick kill and recovery. I like to hit them straight up the rear of the front leg, through the bunched muscle about a third of the way up.

Expectations

A hunter may only get one chance during a weeklong hunt on public land. I advise friends who are new to elk hunting to consider taking any legal elk, unless highly experienced and hunting in an elk-rich area. Most states offer either-sex bowhunting, and a fat cow makes fine eating.

For us, it’s about close range hunting. Close is very possible when hunting elk, sometimes even “too close.” I’ve honestly had an elk actually sniff my broadhead. I once had a bull running at me quickly after I’d called to him, and was hunkered behind a tiny spruce when I realized I was on his trail. It was apparent that he didn’t plan to stop, so I picked a spot where I would hit vitals as he turned, quickly drew my longbow, touched anchor, and released in one rapid motion. He spun so fast the arrow hit him quartering away. From where I knelt to his front hoof print was a mere nine feet. He died quickly and within sight—another example of a shot opportunity afforded by a quick-drawing traditional bow.

The author’s hunting partner, Tom Kelley, with a nice five point taken from an ambush at sunset using a 53# recurve he built.

Traditional equipment fits elk hunting like a hand in a glove. I don’t consider our shot distance limitations as a handicap at all, compared to the advantages offered by our ability to shoot quickly and accurately at unknown distances without having to fiddle with a rangefinder, pick the right pin, organize the peep and the sight window, check the bubble level, recalibrate since the elk has moved again, finally release an arrow, curse because the wrong pin was used, and start over for a try at a second shot. In the time all that requires, I’m often reaching for my Depperschmidt knife after watching my bull fall over.

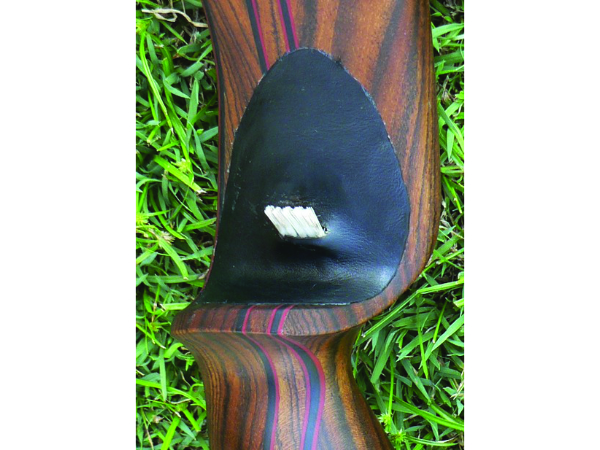

Equipment Notes: The author regularly carries a Kelley longbow on his elk hunts.

The picture of the old Bowhunter looks so much like my father who has passed also to a better place i had to look twice and showed my wife