“Early on, bowhunting to most of us simply meant a ‘walk in the woods’ in search of a game animal.”

Glenn St. Charles

Bows on the Little Delta, 1997

There have been many archers through time who have helped promote the sport of archery and worked to help show bowhunting as a healthy, viable hunting method and management tool for wildlife. However, there is one man whose tireless, continuing efforts have brought bowhunting out of the backwoods and into the main offices of fish and game departments all across the United States. Without a doubt, his ideas and life’s work is why we have the privilege to enjoy the liberal bowhunting seasons we enjoy today. That man is Glenn St. Charles, the last of the true bowhunting pioneers in North America.

Glenn St. Charles was born in Seattle, Washington, on December 15, 1911, to Phillip Joseph (PJ) St. Charles and Coral Barbara St. Charles, née Rouse. Phillip was a timber cruiser. He had moved his family from Alpena, Michigan, to Seattle believing the vast amount of untouched forest land in the Northwest would allow him enough work to best support his family. The Cascade Range, just east of Seattle, provided unlimited work for such a profession, and the family settled into their new home quite comfortably.

A decade later, in 1921, Phillip moved his family to Spokane, Washington, where ten-year-old Glenn was allowed to spend time with his father and his brother, Ray, while they worked in the Kanisku National Forest in northern Idaho. Time spent in timber cruising camps allowed Glenn to learn about the ways of nature, both flora and fauna. While he learned of logging, he also learned to hunt and fish. His job while the men were out working was to wash dishes, cut wood and keep “…a back burner crock of sourdough happy, bubbling, and burping by feeding it potato peelings.”

In 1924, the family moved back to the Seattle area, making residence in the suburb of Fauntleroy where the elder St. Charles changed careers from timber cruising to real estate. It was here, in 1926, that Glenn had his first contact with the bow and arrow. Along the shore of Puget Sound, housewives would toss their garbage off the seawall, attracting local sand sharks. Glenn and his young cronies had bows made of hazelnut, strung taut with meat wrapping twine, and arrows of willow shoots upon which were fixed sharpened nails. With these crude weapons the boys spent hours stalking the sharks, occasionally scoring a hit.

Glenn with a Rocky Mountain goat he killed while hunting in Tweedsmuir Park in 1955.

At the same time Glenn was getting interested in the Boy Scouts. In his Boy Scout’s manual, he read about the yew tree and how its wood would make a good bow. Since the Seattle area is near some of the finest Pacific yew one could find, he promptly set out and harvested some branches from a tree near his home, made his first yew bow, and earned his merit badge in archery.

Through his association with the Boy Scouts, Glenn was able to purchase a seasoned Tennessee cedar stave and proceeded to build a bow from it with nothing more than a spokeshave and rasp. Soon more of the Scouts became interested in what Glenn was doing and more staves were ordered, bows built, and Glenn spent the next two years teaching archery at Camp Parsons, the Boy Scout summer camp on the Olympic Peninsula. These two years would cement the love of archery in the young St. Charles, a love that has consumed his entire life.

After graduating from high school in 1930, Glenn and three of his buddies took a Model T Ford to Wyoming where they spent each of the next few summers working for the parents of one of his friends, Sandy Stewart, building the Kilbourne Dude Ranch. Glenn married Marjorie Ernestine Kneisel of Sheridan, Wyoming, and the two of them moved back to Seattle where Glenn, along with his new bride, renewed his interest in archery.

1942 found Glenn working for Coates Electric Company in Seattle, a company that was building submarine parts for the U.S. Navy. He was still dabbling in his archery, but the war effort kept everyone busy. Then in 1948, his wife Marjorie passed away leaving Glenn alone to raise their nine-year-old daughter, Linda.

After the war Glenn quit Coates Electric and went into the archery business full time. He opened his shop on Airport Way in Seattle where he met Margaret Lorraine Remick and married her. Together they worked in the shop, many nights staying up until 2:00 a.m. filling orders. Glenn had been talking with Fred Bear and soon became a Bear Archery dealer. Then in 1949, he and Margaret sold their place in Seattle and purchased five acres of wooded land south of town where they built a two-story building that would serve as their home and archery shop. It was remote, and quite crude. “We didn’t even have a toilet here. We had to go out in the woods, you know. Margaret likes to tell the story about the time some fancifully dressed lady got out of a car out here on the highway and ran into here and wanted to use the bathroom. Margaret told her we didn’t have one.

“ ‘Well, what do you use?’ she said.

“ ‘Well, we use the woods.’

“The lady asked, ‘Could you tell me where the woods are?’

“You could sit out here on the highway for an hour before another car would come by. It was out in the country back then.”

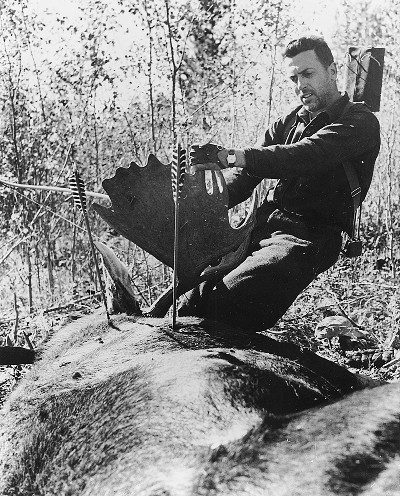

Glenn took this Canada moose while bowhunting in Tweedsmuir Park in British Columbia, 1954.

Glenn and Margaret continued to build Northwest Archery into one of the largest archery shops on the West coast. In the 1940s he learned a new process of laminating wood and fiberglass to make bows that worked much better than self-wood yew bows. In 1952, he designed his finest shooting recurve, the Thunderbird, in both 63” and 67” lengths. The Thunderbird had working recurve limbs, as opposed to the static limbs on all the other bows on the market and was an instant success. But Glenn became concerned about getting too deep into bow building, and eventually made the decision to stop production after 400 bows. He showed two of them to Fred Bear in 1953, but Fred wasn’t too impressed since he was already producing two static recurve bows—the Grizzly and the Kodiak. Interestingly, in 1954 Bear Archery introduced their first working recurve bow, the Kodiak II.

Glenn had been talking with Fred Bear for several years over the phone. They had a lot in common. Both of them were writing about bowhunting and bows and arrows. Fred was getting yew from Glenn and Glenn was getting Osage from Fred. It was a back-and-forth thing. But they never met until 1953 in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, at the NFAA Field Tournament. They discussed a lot of things, but the main gist was Bear’s interests in the Northwest and the bowhunting possibilities Glenn could set up for him. Since Glenn was starting to expand his business as well, he was interested in being represented back east. The two men agreed to expand their business ties and Glenn became Bear Archery’s West Coast Warehouse.

Glenn designed his own broadhead that he named the Mickey Finn. It was a 2-blade design with an 11/32” ferrule and weighed a hefty 175 grains. Released to the market in 1953, it gained a reputation of being a hard hitting and extremely strong broadhead. But, as Glenn had done with his earlier Thunderbird recurve, he stopped production and the head dropped from wide-spread use. Today, it is an extremely rare broadhead and can be found only in collections.

Ever since the era of Saxton Pope and Art Young, bowhunters had been struggling to gain national recognition in the outdoors community. They had to prove that their method of hunting was, “…truly a manly, efficient way of hunting.” The going had been slow and labored, and many individuals played important roles. Bowhunting became recognized as a legal hunting method in Wisconsin in 1931, thanks in large part to the efforts of Roy Case, Aldo Leopold, and Carl Hubert. Then, in 1934, a Wisconsin bowhunting-only season was established. Within a few years other states followed: Minnesota, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois, eventually leading to several western states establishing bowhunting seasons as well. But bowhunting was still not widely accepted.

In 1957 Glenn and Keith Clemmons ventured north into the Little Delta region of Alaska looking for unique bowhunting opportunities. Here Glenn admires a fine Barren Ground caribou he took there.

In 1940, the National Field Archery Association established the Art Young Big Game Award System. It was at this time that Glenn became active in the NFAA and together with bowyer Kore Duryee of Seattle the two men went to the Washington State Game Commission to help preserve the young bowhunting seasons and expand new ones. The results of this meeting determined the direction of bowhunting across the entire nation. As Glenn recalls:

“I accompanied Duryee to a two-day Washington State Game Commission meeting in the spring of 1941. The Commission was in the process of setting the season dates and we had gone to present our proposals on behalf of the bowhunters. Washington had enjoyed three previous bowhunting seasons and we believed an annual archery season would continue. However, for no apparent reason, the Commission suddenly decided to do away with bowhunting. Of course, we were shocked and went away disappointed. After talking it over, we decided to return the next day and try again. We were successful, but the humiliation of this second effort left me with a determination to commit myself to changing the bowhunter image.”

The result was a push by Glenn and a few others to bring bowhunting into the spotlight of the game departments and show them that bowhunting was indeed a viable tool for harvesting big game and aiding in wildlife management. Glenn was the Vice President of the NFAA in 1956. His role was that of Big Game Chairman. He had been upset for many years with the role bowhunters played and how they were being treated “…like trash…laughed at, called doe killers…[we] were ridiculed.”

Glenn was aware of the Boone & Crockett Club and what they had accomplished for gun hunting. There was a fellow named Connors who was in the NFAA and was also a member of the Boone & Crockett Club. He mentioned to Glenn how the organization had helped the sport of hunting, and Glenn thought the same concepts could be used to help bowhunting. So, he contacted the president of the Boone & Crockett Club and asked him how they started their Club. From that moment the seed was planted….

John Young, the NFAA secretary, gathered all the information for Glenn, and by 1957 they had the program outlined. They presented the idea of game scoring to the directors of the NFAA. In the meantime, Glenn went hunting on the Little Delta with Keith Clemmons and told him about his idea of a scoring system for bowhunters. When Glenn returned from the hunt, the NFAA still hadn’t addressed the idea. “They were too involved with how far shooting stakes should be, how they should be marked, the size of the targets and so on. They weren’t receptive to the idea.”

Seven months after Glenn had presented the idea, the NFAA board finally approved it. So, in January of 1958, they launched the program. All hell broke loose! Mail suddenly began to pour into Glenn’s office. People finally felt they had a place to hang their hat, something to prove. It was so overwhelming Glenn started to charge .50¢ to enter an animal in the records. From this point on it was all on Glenn. He and his local committee ran the records program by themselves. “I had a hold of something I couldn’t let go of…like an electric wire…so hot that I couldn’t move, couldn’t do anything…I didn’t have any time without help.”

As soon as the program was up and running Fred Bear wanted to have a trophy display in Michigan in 1958, that same year. So, Glenn and his small committee figured out which animals were the new World Records and shipped all the information back to Michigan, contacted everyone who was involved, and put the show on.

When Glenn returned from Michigan the NFAA agreed that the records program should be a separate group, so for the next two years Glenn and his committee trained new measurers and entered animals into the records.

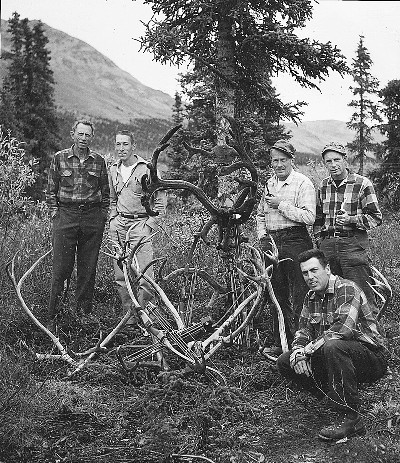

In 1959, Glenn returned for his third—and final—trip to the Little Delta. Left to right: Fred Bear, Dick Bolding, Bob Kelly, Russ Wright, and Glenn, kneeling.

In 1960, another Awards Banquet was held in Grayling, Michigan, where about 35 bowhunters gathered to discuss the future of the awards program. It was agreed that this new program needed its own identity—it needed to be its own organization. The group decided to name this organization in honor of the late Saxton Pope and Arthur Young. Since all the existing records to date had been compiled under the NFAA, Glenn approached the Executive Committee and expressed the desires of the newly formed Pope & Young group. After much debate, the NFAA agreed to release all the records. Six months later, on January 27, 1961, the newly formed Pope & Young Club was born.

The Club continued to evolve under St. Charles’ leadership and by 1963 there were 30 Regular members and 80 Associate members. The total number of animals entered into the records was 361. The Club was moving in the direction Glenn had foreseen, and on June 5, 1963, the Club incorporated.

In 1966, the Club’s bylaws were approved and adopted allowing the first elections to take place. On November 20, 1967, Glenn St. Charles was elected as the Club’s first president. His leadership had taken the Club from just an idea into a growing entity, one that would be used to prove to the nation’s fish and game departments that bowhunters were not just doe killers but were capable of harvesting mature big game ethically. It opened the door for all bowhunters, and in a few years almost every state in the nation would follow suit and develop archery seasons.

The compound craze hit around the mid to late 1960s, but it never took hold until Tom Jennings got involved and honed the device into a real shooting machine. The compound bow had come of age and archers everywhere were making the change from their traditional bows to this new device that allowed the user the ability to add lots of accouterments. And even though most archers began to embrace this new device, many questioned its effect on the outdoor ethic and what was happening to the traditional aspect of bowhunting. By the late 1980s, there was a strong movement back toward the traditional ways, and Glenn and his family were once again harvesting yew from the coastal mountains to meet the demand for longbows made from this sweet shooting wood. They also imported Osage orange from the Midwest to make selfbows. “We are going full circle back to the basics of the old reliable yew and Osage that relate to rawhide, sinew, glue, beeswax, and the smell of cedar and burnt feathers.”

One of Glenn’s most important contributions, in addition to his formation of the Pope & Young Club, was the Northwest Archery/Pope & Young Museum in Seattle, Washington. The museum was created more by accident than by any determined pursuit. Throughout his life, Glenn acquired everything he could that had to do with the history of archery. He eventually ran out of room and one day loaded up a truckload of old magazines and was headed to the dump. His son, Joe, saw the truckload of magazines and decided they should hold on to them a little bit longer. He was concerned about it, reflecting on all the information in those magazines. He persuaded his father that they should build an addition to the house and archery shop to hold and display all this archery history.

While contemplating the costs and feasibility of adding on the existing building, Joe had been conversing with Dr. Grayson, who had some of Saxton Pope’s bows that he had bought several years earlier. Dr. Grayson was getting up in years and was concerned about it. He drove up to Seattle one day to see what Joe was doing about all this archery history. Joe told him about his idea to build a museum where all the history could be placed on public display. Well, Dr. Grayson liked the idea and offered to sell all his Saxton Pope collection to St. Charles for the exact same price he had paid for it many years before. The problem was the St. Charles family couldn’t afford the price tag of $2,500. Glenn told his hunting partner, Bill Jardine, about his dilemma and Bill whipped out his checkbook and wrote Glenn a check for the entire amount, then drove down and picked up the collection himself. When Bill returned with the collection, Glenn opened up a box of arrows that belonged to Saxton Pope and in there were several arrows made by Ishi. This was the start of the museum.

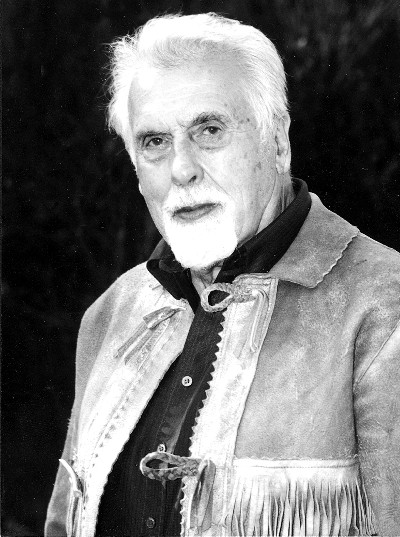

Glenn St. Charles in his renown smoked moose hide coat.

The museum was sold to the Pope and Young Club and moved to Chatfield, Minnesota. That building has since been sold and a new home for the museum is underway at this writing. But for many, many years this wonderful museum had tens of thousands of visitors, from all over the world, come through its doors in Seattle. This collection of bowhunting history is the most extensive to be found anywhere and was made possible by the dreams of Glenn and his son Joe.

Over the course of his archery career—a span of some sixty plus years—Glenn managed to hunt all across America and Canada, taking several exceptional animals and sharing his love of the outdoors through his writings and lectures. His first book, Billets to Bows, is a masterpiece in the art of taking raw yew and turning it into a finely crafted bow. It is the written version of his excellent video of the same name, which shows the same process in a wonderfully choreographed film.

In 1997, Glenn released his much-anticipated biography, Bows on The Little Delta. This book covers the entire story of Glenn’s life, both personal and archery related, and is richly illustrated.

Glenn passed away September 19, 2010 at the age of 98. He was a tireless promoter of bowhunting and its traditional values, a path that has been his whole life, and is the last of what I term The Old Guard. He, and his cronies, were the true pioneers of bowhunting in America. For the most part, everything we, as bowhunters today, experience has been done before by these great men. And Glenn St. Charles is the last of these bowhunting greats.

Leave A Comment