It’s my goal to become as familiar as possible with the lives of the flora and fauna in my eco-region. There is an excess of 3,500 plants in the California Floristic Province, so it is unlikely I will know them all in my lifetime. Likewise, the kingdom Fungi holds a great diversity and abundance of species, and while I strive to learn one new edible mushroom per year, I am constantly walking past mushrooms I cannot name. However, there are only so many mammals in my region. I have seen all the mammal species here larger than a short-tailed weasel, and I have seen a representative species of the smaller Genera. I am familiar with the sign they leave on the landscape, their interactions with the biotic and abiotic environment, and their behavior. I am comfortable in the forests around my home, and this intimacy with large mammals extends to all locales where I have resided. Which is why I was so excited to hunt collared peccaries in southern Arizona, because here was a large mammal that I was completely unfamiliar with.

A micro view of an agave lechuguilla (small lettuce) feeding area. Javelina are often seen eating and romping in patches of this plant.

Heather and I traveled south for some winter solar exposure, dry air, and archery javelina hunting on a member group hunt hosted by Rick Wildermuth of the Professional Bowhunters Society (PBS). PBS members host these hunts as a means for like-minded archers to gather around a campfire, share stories, and bowhunt together. Rick has been graciously hosting the Arizona javelina and deer hunt for eight years. Javelina hunting has been a dream of mine for a few years, so I jumped at the opportunity to chase these tropical ungulates and share in a PBS camp. The other PBS members in camp included Ron Grist, Kevin Hall, and Matt Wilson.

We pulled into camp as the sun set, and on the surface the desert always seems devoid of life. A cursory glance over the landscape appears bleak and waterless, yet a detailed look reveals traces of life etched in the sands everywhere. Amidst a land of rock and thorny brush, wildlife abounds. But what do javelina eat, do they need free water, or can they acquire it from the moisture in their food, where do they sleep, and how do they traverse across the hills? These were the questions I held as our hunt unfolded, and the peccaries were keen to answer.

The trail we followed our first day led us to an amazing discovery. Javelina had eaten into the center of a desert agave plant, feasting on the moist flesh. Deer had detected this source of moisture and were also consuming the agave’s meaty heart. The two groups of animals had fed so deeply into the agave that I could reach my arm elbow deep into its depth. For a deer or javelina to currently eat out of that pit, they would have to submerge their entire head past their ears into the plant! We found the behavior fascinating.

A micro view of an agave lechuguilla (small lettuce) feeding area. Javelina are often seen eating and romping in patches of this plant.

Tracks of a squadron of peccaries we followed on the third day of the hunt showed us how they consume prickly pear pads, with a seemingly careless attitude toward the spines. Another trail on the fifth day led us to a lechuguilla field where javelina were tearing up the leaves and eating the base of the plant into the roots. On the seventh day we saw digging sign for a root that was either from mesquite shrubs or pancake prickly pear; we were unable to figure out which root the plant belonged to. But their diet was becoming illuminated, and we began to perceive the landscape from the perspective of our quarry.

Their choice of bed sites was equally as interesting. Peccaries are really a tropical species, and the northern limit of their range is mostly dictated by cold weather. Nighttime temperatures were hovering in the 20s the first half of our hunt, and javelina behavior reflected their lack of underfur or fat. Morning bedding locations were positioned perfectly to receive the warming rays of the sunrise, tucked up tightly against some Spanish bayonet clumps and facing southeast. Later in the hunt, and during the middle of the day when temperatures warmed up, they chose to rest in the shade of mesquite shrubs. These types of beds were easy to see, but when they crawled into a bed in the dense bear grass a guy would be hard pressed to know if he stepped on one.

Interacting with the collared peccaries was even more exciting than learning about their lives from reading sign. My first encounter occurred right at sundown on the first day and ended briefly. Aside from a few confrontational “woofs’’ as I walked up on the one I had shot, the hunt was over quickly. Heather, on the other hand, had some incredibly close observations.

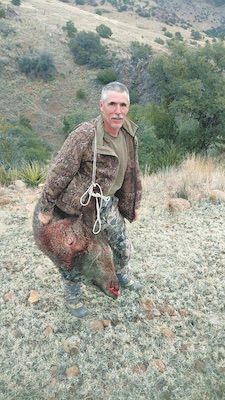

Rick Wildermuth, the host of this hunt, with a javelina he took with his longbow. Rick graciously hosted this PBS Arizona deer and javelina hunt for eight years now.

After trailing a squadron, spotting them feeding, and circling around downwind, we stalked into recurve range. I stayed put 30 yards from the group and watched Heather maneuver into the middle of them. We then experienced our first, long intermingling among foraging javelina, and could hear the low, rhythmic feeding grunt. It had a hollow sound and was uttered every second as if on a metronome. The grunt implies contentment, and, like the soft talk of cow elk, lets the rest of the group know that everything is alright. Furthermore, when researching literature of collared peccaries back home, I found that the feeding grunt also allows javelina to maintain social distancing to prevent subordinate animals from intruding on the personal space of a more dominant animal. When one’s space was invaded, a scuffle could occur, and Heather witnessed two javelina sparring with open mouths due to an intrusion.

She watched a sow nursing young from a handful of yards away. When the wind switched, the sow alerted the group to our presence; the sow stood guard until most of the squadron had started their escape, but one animal turned to face Heather and opened its mouth wide exposing the long canines. The message was clear, we were being told not to pursue. Having already spooked that squadron twice, we nicely obliged to the request and headed back to camp for the night. Over the course of the hunt, Heather loosed three arrows, but all were clean misses. I considered that a success, as they were her first arrows fired at big-game animals during her first year of bowhunting.

Tracking proved a great method for locating a group to stalk. Of the four days we cut fresh sign, there was only one that we couldn’t locate the animals. Even over rocky ground where tracks were impossible to see, their feeding sign was plentiful enough to stay on the trail. A challenging aspect to trailing them was the abundance of older sign. Javelina have small home ranges, and they circle back over their own trails creating a confusing mess of old and fresh spoor, especially in feeding areas. However, their small home range also proved beneficial, because when we did cross fresh tracks we knew they were not too far away. And when we couldn’t locate a peccary, there were plenty of quail, rabbits, and hare to keep us busy.

I continued to learn about collared peccaries, reading a synopsis of their natural history when we were home. They are uniquely American; the fossil record indicates their presence on the American continent for at least 30 million years. While their outward appearance suggests a similarity to old-world swine, their form and behavior is the result of convergent evolution. The two groups of animals (wild hogs, Sus scrofa, and javelina, Pecari tajacu) are as different as deer and sheep. The collared peccary has evolved its own version of a multi-chambered stomach, which equals ruminants in its ability to extract nutrients from vegetable matter. And they possess a unique scent gland located on the top of their back slightly anterior to their hips.

The author’s wife, Heather, practicing before her hunt.

This gland is the source of colloquialisms like skunk pig, and the rumors of their inedibility. Removing the gland is a simple affair when skinning an animal. The hide pulls free from the gland, and you can grasp the fatty tissue to carve it from the carcass easily. If care is taken to avoid spreading oils from the gland onto the meat, then the rumors of their poor taste are completely false.

We consumed most of the animal I shot while in camp, and the meat was delicious. We ate chopped heart, tenderloins, and shoulder roasts sautéed in a cast iron skillet. We grilled backstraps over locally sourced mesquite coals. Even the liver was mild and pleasant, seared in a pan of onion and fat. At home we simmered the head and pulled the meat off to make posole, a Mexican dish that traditionally uses pig heads. The food was incredible.

I’d like to thank Rick for graciously hosting this hunt and inviting us along. The scenery was majestic, camaraderie entertaining, sunshine enlivening, and game abundant. What more could we ask for from a hunting adventure? Well, there is one more thing: I became acquainted with a fellow animal who shares this world with us. The life experience as a collared peccary became a bit more clarified, and one more thread of connection between the natural world and me was tied.

Preston is a Senior Tracker, and author of Tracking the American Black Bear. He works as a biologist with the Yurok Tribe and resides with his wife in north-coastal California. Now that Heather’s parents have retired to Arizona, Preston and Heather plan on taking advantage of family visits to camp and hunt during the winter months.

References: Behavior of North American Mammals, Mark Elbroch & Kurt Rinehart.

Equipment Notes: Heather was shooting a Bear Kodiak Magnum recurve, Easton Gamegetter arrows, and STOS broadheads. Preston was shooting an Osage orange selfbow, Douglas fir Surewood arrow shafts, and 200 grain double bevel Grizzly broadheads.

Knifeless Skinning

Brain-tanning the hide has become an interest of mine as I continue to learn methods of utilizing the most from an animal. However, after skinning dozens of animals, when I started to tan my own hides I had to re-learn the proper method of skinning. Previously, I had used my knife to slice the hide free from flesh, and while I was careful to not cut into the hide I would make a few mistakes and put a couple extra holes in the hide. Moreover, the use of a knife almost always results in score marks on the skin, which become a problem later during the stretching and drying phase of home-tanning. With inspiration and instruction from Demetri Voelker and Jay Sliwa, as well as videos by Woniya Thibeault on her YouTube channel Buckskin Revolution, I learned how to use my fists and elbows to pry a hide from a carcass with very little use of a knife.

After the initial incisions down each leg, up the middle, and around the neck you shouldn’t need your knife except for possibly freeing the hide from the brisket. Use your fingers, fists, and elbows as wedges to separate the hide and flesh. It helps to have the animal hanging, if possible, to create leverage. This method of skinning allows you to detach the skin from the “twitch muscle” (as Woniya calls it), that thin membrane of flesh under the hide, which results in a clean skin requiring little to no fleshing afterwards.

I have now employed this technique on a couple of deer and elk, and this javelina. I am amazed how a bit of effort up front saves a lot of time later, and results in a better quality end product. My friend Don Thomas advises skinning javelina with a partner. One person can pull and handle the skin, while their partner separates it from the muscle. In this fashion, the hand that touches the hide never touches the meat.

- The author using his fist to wedge between the skin and twitch muscles.

- A hide skinned this way results in a clean skinning that requires no fleshing.

Leave A Comment