Bowhunting to me has always been, in its truest form, a reason to dive into the natural world. I feel the act of hiking through the mountains comes with greater satisfaction when the purpose of the hunt is at the root of the adventure. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy other forms of engaging with the mountains be it backpacking or running throughout the summer months. But I am convinced that no activity other than the historical pursuit of predator and prey provides a true understanding of the woods.

In ritualistic fashion, each September since my years as a young man I have taken to the woods with bow in hand with the intention of pursuing elk. Or perhaps to my earlier point, in pursuit of early mornings looking over vast aspen-covered hills and craggy canyons, long days walking, consciously making each foot fall in silence, and the comfort of a down bag as darkness folds over the wilderness.

Camp in a bear’s paradise.

For those who have not yet experienced the last of our nation’s untouched wilderness, the concept of satisfaction in the journey may be difficult to understand. While the enjoyment of success in taking an elk with stick and string and the bounty it provides to our family is undeniable, the challenge of the pursuit offers a pathway into areas we are typically encouraged to avoid with “stay the trail” initiatives and the webbed roadways providing a pseudo-experience of nature. In the absence of human pressure, these are the areas closest to their natural state.

This past September I found myself among tangles of oak and intertwined quakies searching for a dry spot along the bed of a small creek. We had packed in a short distance to drop our gear that afternoon and, with little daylight left, determined our best option was to settle in and plan out the days ahead. Although I have managed to find my way into the elk woods every September since finding my passion as a bowhunter, this year was slightly different. I was lucky to be sharing the last few weeks of the season with two great friends when typically, I find myself in this pursuit alone. Danny and Chad are not only two good friends, these two individuals I would class with any of the most consistent hunters I know. Neither one has specialized in a specific species, although it could be argued when looking through their history of success that elk are at the top of the list. They have a knack for moving through the woods without disrupting the scene around them. Their knowledge and understanding of animal behavior and dynamics has matured with this ability to observe the world in its natural state. Due to conflicting responsibilities, hunts, and life in general, we found ourselves looking down the last 10 days of Colorado’s season without having spent a day in the woods in pursuit of elk.

Planning the trip, we went to sorting gear, packing food, and studying maps of an unknown area we had seemingly thrown a dart at given some basic knowledge in an attempt to find the sanctuary. The elk were inevitably pressured to find a home to escape human presence throughout the long season. As we talked through our plans, we found ourselves giddy with excitement. Any social pressure from our daily lives was long gone; it’s funny how the sound of a creek and dusty aspens can have that effect on one’s being.

The author peering into a north facing section of timber. (Dan Clum photo)

With the growing popularity of western hunting and the unrestricted sale of hunting licenses in the state, any hopes of locating virgin country should be wiped from the mind. Aldo Leopold noted that while nature may exist only in isolated areas, there is no guarantee it will be found in its pristine state. Aside from his naturalist philosophy, I believe there is much to be learned in his words for the pursuit of a late archery season Colorado elk; otherwise, do not expect to give the call of what may resemble a lost cow to have the attention of every love-sick bull on the mountain. I often wonder what Leopold and other early naturalists would think if they observed the state of today’s wild country. On one hand, it is incredible that in today’s world we can still take to the hills to see a semblance of what the country looked like hundreds of years prior. On the other hand, it can be disheartening to see the increasing traffic and consequences that come with it. In any case, the cards had been dealt for our late season hunt and we were in for a challenge.

Our first morning started with a fresh cup of instant coffee and warm oats. Through a series of moans and grunts, we determined our first course of action was to beat the brush to the top of a ridge roughly a mile out. We worked our way up a cut in the hillside, conveniently steep enough that erosion limited much of the oak growth. Pushing upward in the silence of the early morning, we finally summited the head of the ridge and settled into a seat we each kicked into the pine duff. We figured there wasn’t much of a point in pushing through the next set of brush prior to daylight. There was little chance of moving quietly through the dense and brittle dry underbrush. The common theme of the area we had chosen was thick. Visibility was limited to five feet unless overlooking a boulder field, which happened to be sporadically placed throughout the dense, jungle-like forest. Every description made this area inhospitable to anyone bipedal, yet it was perfectly suited for the elk’s seclusion.

Danny Clum, contemplating the lack of responsive elk.

As the sun began to warm the eastern horizon, our theory was confirmed with a break in the silence as a strained bugle rang out from the canopy below. Immediately confirming the wind, in silence the three of us moved across the ridge, finding a cut filtering down to a bench of aspens and ferns. To avoid unnecessarily alarming the herd, we moved without calling, and positioned ourselves on the same topo line with the lead cow. The early morning wind had stayed consistent; the elk continued to go about their routine trading vocalizations and audibly splashing in a nearby wallow. This is that time as a traditional bowhunter where you understand the complexity of the pursuit in comparison to more modern trades. A mere 50 yards away through thick underbrush, we might as well have been miles from an opportunity. However, in trade of a loosed arrow, we were engrossed in the sounds of September. The bull glunked and hoofs turned over rocks as they milled through the forest, at times well within range had the oak leaves fallen.

With the sun continuing to rise overhead, the sounds slowly faded over the crest delineating the timbered canyon below from our current position on the lush bench. As a seasoned couple of hunters, we understood the benefits of patience. Patience as contrasted to overzealous confidence, chasing the herd into their beds. In a low density, high pressure unit, we understood the benefit of restraint. Backing off to a local watering hole for the afternoon, we anticipated as the conservative move, hoping that the high sun would lead the bull back to a mud bath before evening. As it goes, hunting is not a science. While my analytical brain would prefer a logical solution to each hurdle we encounter in the woods, the pure fact that this is not the case is what brings excitement to the pursuit. The lack of predictability had led to a sunburned forehead, aching back, and only a few squirrels courting one another at the water’s edge.

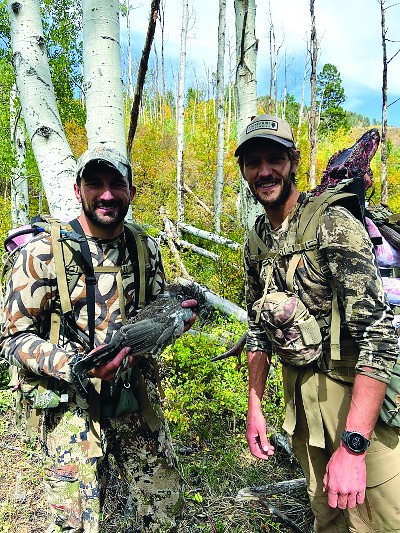

Dan Clum (left), arrowed this camp meat on the way back to the tents.

With the day fading to darkness and us retreating off the mountainside, the elk took to their chorus. The bugles reverberated off the walls below as the bull gathered his harem in seeking the nightly festivities. The cows chirped as they herded their young through the weaved maze of oak. As a whole, the group moved in unison upward, yet a few hours late. Although we had not crossed paths within the range of my bow, it was hard to leave our first full day in the woods with anything but a positive outlook for the days to come. The mere fact we had located a vocal group of elk in the absence of other humans seemed unlikely. Our remaining nine days to be spent on the mountain parlayed a forgone conclusion.

Now this would be the point in the story where one might think we amble on about the peaceful darkness or sounds of crickets carrying through the night. The reality of the situation is somewhat comical to relive. Given the thick underbrush and lack of flat terrain, we had forced ourselves to camp on a small set of game trails happening to intersect between the two tents. The previous night while gathering water, I had come face-to-face with a small bear on one of these two trails. Observing the sign in our surroundings, this encounter was no coincidence. The ground was littered with bear droppings as if we were camped in a cattle pasture and every low hanging service berry limb was stripped clean. Scattered stumps were overturned in search of protein to supplement their berry rich diet. This was one of the “beariest” thickets I had come across in my time walking through the forest. While I am not particularly uneasy around black bears, I have been taught to have a certain respect for the critters. As such, the first few nights camped along the stream were more restless than perhaps those spent in a high alpine basin. Yet the uneasiness was ultimately unwarranted as one might guess. Any animals walking the night were surely keen enough to avoid the presence of a couple stinky hunters rolled into their down bags.

In the days following that first encounter with the herd, we worked as a team to suss out the solution to the unusually thick cover and steep terrain. The animals were cagy and unlikely to respond to aggressive calling. The oak was dense, thwarting any reasonable chance of a stalk. The wind was unpredictable as the sun warmed the hillsides and the uneven terrain took the currents where it wanted.

We were striking out at each turn, losing to the nuances of the woods. Now several days into our shortened season, we sat deflated, trading conversation on a log positioned uphill of a likely mid-day water source. Even the pea-brained grouse had outsmarted us, flushing in front of a cow that had just worked her way down nearly to the water’s edge inevitably presenting a shot. Persistence has historically paid in success; a comedy of errors when the hunter consistently is within striking distance will open to an opportunity, yet in this go around the coin recurrently landed heads down. The unwillingness to accept the odds resulted in a conversation to push over to an adjacent saddle in hopes of aligning the prominent wind direction with the thermal flow, setting up in what was presumably a transition area between daytime bedding and water. In an effort to maximize our cover, Danny and Chad elected to stay on the east side of the ridge while I moved up and into the adjacent westerly canyon.

The author and his oak brush bull.

The natural escalator of dinner plate talus led me up a steep chute to the desired saddle ahead. With midday heat beating my brow, beads of sweat rolled down my neck to puddle above the lumbar pad of the heavy pack. As I pulled my knees toward my chest, I envisioned the elk finding refuge under the north face of the ridge along the fingers of dark timber. For good reason, they knew this area as a place to find sanctuary from the outside pressure of Colorado’s archery season. Who else would be out here, miles from any established trail, bushwhacking through something resembling an arid version of a humid, tropical jungle, and now frying like an egg while climbing this talus slope?

My thoughts drifted to the reward likely ahead, a new water source above an established bedding area where I would find a respite for the remainder of the hot afternoon awaiting the evening activity…if only. The anticipated water source was nothing but an underground spring, flowering some green grass and willows to deceive a far looking eye. While the defeat was ever present, I had not let my instinct as a hunter wane. Recognizing the increasing elk sign en route to the assumed watering hole, I mimicked a lost cow, occasionally sending a light mew into the timber and strategically popping sticks while quietly easing through the shadows.

Packing meat and prepping for a long haul out.

As I sat in contemplation while my initial plan was deflated, the keen sense of a hunter was instinctual. With the slightest “pop” from the thicket below, my eyes rolled to the left to find the tips of a curious bystander’s head gear cresting the near horizon. Presumably, the imitative noises of a lone cow peaked his interest, rustling him from a midday bed to investigate a potential mate. Allowing him to continue his search, I quickly nocked an arrow, came to my knees, and sent the softest call into the aspens where his rump was last seen. His response, immediate, cracked my ears as he whirled and picked up a trot. I followed his hooves under the canopy, anticipating his approach. His head now in view, the pearls of his eyes were visible as he rolled his head back, releasing his angst. In a matter of a moment, I trailed his rolling shoulder muscle and loosed the arrow. Over the course of minutes, I was taken on an amusement ride of emotion, only understood by those who have experienced it. The hours and days, the persistence, the beauty of the woods all crescendo at the moment of interaction where the bow is bent to full draw. The following hours to be spent riding the high of adrenaline in preparation for a long and dark walk back toward civilization.

I will continue engaging in a multitude of outdoor activities, immersing myself into the wild, searching for the closest form of a true wilderness. Yet for me the closest interaction with these wild places cannot be replaced with an experience other than the interaction of hunter and hunted. As hunters, we learn to understand our surroundings beyond any superficial proficiency. This understanding provides an unprecedented appreciation of the wild and the wild animals that call it home.

Equipment Notes

On his elk hunt David Hoff shot a 64” Wengerd Ibex, and Day Six arrows, tipped with Cutthroat broadheads.

Leave A Comment