Bowfishing has become an increasingly popular sport. Some of us indulge in it during the off-season to keep hands and eyes tuned for big game hunting in the fall, while others see it not as a means to an end but a sport unto itself. Whichever way bowfishing appeals to today’s archer though, there’s plenty of gear out there to help make him successful and no shortage of “how-to” literature to get the beginner up to speed quickly.

This was not always the case. Not long after archers began hunting deer and small game with the bow and arrow, they realized that besides fur and feather, an arrow might have possibilities for bagging finny targets, too.

One of the interesting aspects of early bowfishing is the lack of a “beginning” point, so to speak. The process seems to have developed by trial and error in many parts of the country over about a decade in the 1940s and 1950s. A piece by Sam Dinerstein that appeared in Archery magazine in March, 1948 describes a good example. He begins:

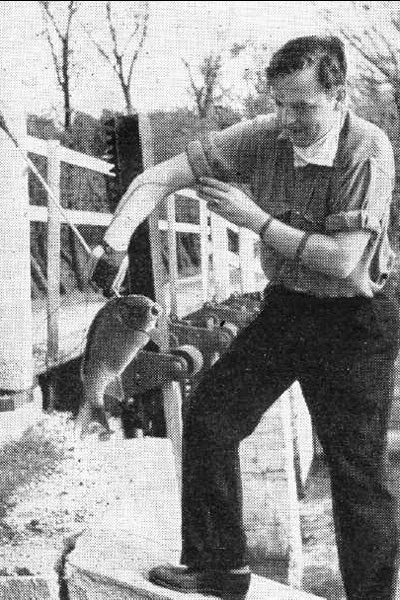

John Fink holding up a carp.

“Our introduction to fishing with a bow and arrow came suddenly and informally one April day. Henry Maager, George Count, Ole Severson, Nate Dinerstein, Red Hurdis and yours truly were constructing the Ouisconsin Bowmen Field Course in Delavan, Wisconsin, and we stopped on the bank of Archer’s Creek to talk to Doc Gregerson who had driven over from Elkhorn to see our new course, when one of the boys noticed that suckers were swimming up the creek. We dropped our tools, grabbed our bows and quivers from our cars and rushed back to the creek.

“The first two fellows to reach the bank let go with broadheads with disastrous results to the arrows. When the rest of us reached the creek they held up their broadheads with the points rolled up like the top of an opened sardine can. The creek is about eighteen inches deep and its bottom consists of a layer of rocks of assorted sizes.”

Since broadheads were obviously not the best choice when shooting into a backstop consisting of stones, a new approach was needed. Next up were roving arrows with non-skid field points.

“For the next half hour we had a wild time,” Dinerstein reported. “The arrow would penetrate a sucker and then come to a stop when it hit a rock, with twenty inches more or less of shaft sticking out above the fish. The arrow promptly toppled over due to its weight throwing the sucker on its side.”

Since nobody had thought about using line at that point, retrieval of the arrow (and sometimes a fish) presented a problem. In one instance a fish was shot in such a way that the arrow wedged between a couple of rocks midstream. Sam records that the archer “took a running jump and landed in the icy water up to his knees with a mighty splash” whereupon he managed to retrieve his arrow and the fish.

The crew members must have been pretty good shots (or had a lot of arrows with them), since the writer goes on to say: “In half an hour we cleaned out the entire run of suckers. Since it was early in the spring in ice cold water, the suckers were edible. Red and Ole strung up the fish through their gills on willow twigs and took them home for a fish fry.”

After this impromptu baptism into what, for them at least, was a totally new sport, the bowfishing bug evidently bit the group hard. With the suckers gone, they turned their attention to carp, which were abundant in nearby Lake Delavan. The lake’s soft bottom meant no more shattered shafts or bent points, but a miss meant that the arrow would stick in the muddy bottom, never to be seen again.

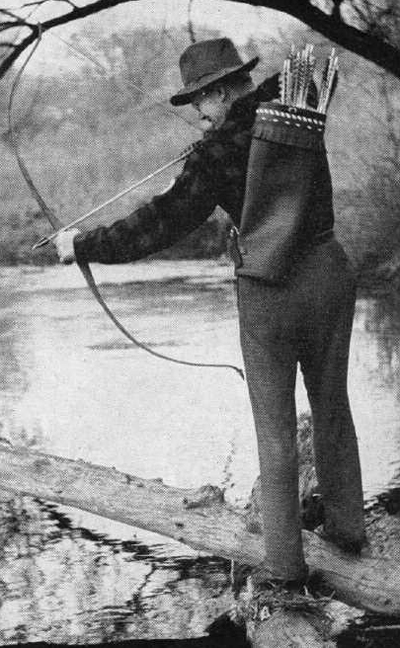

Ole Severson aims at a sucker in Archers’ Creek.

Unfortunately, a hit usually resulted in a lost arrow too, because the big, barbel-mouthed bottom feeder would swim off carrying the shaft with it. Still, the stricken carp were not wasted because after they died they became food for turtles. “In fact,” Sam recalls, “as we returned day after day after finishing work for an hour of bow fishing, the snapping turtles learned to congregate just beyond shooting range waiting for wounded fish.”

Evidently the guys now started running short on ammunition, which finally prompted them to start thinking about attaching a line to the arrow shafts. Since bowfishing reels weren’t available, they merely coiled the line on the ground near the shooter. The next day, carp killers Ben Warmey and John Fink tried the method out.

“After several shots a hit was registered on a carp which proceeded to get away as fast as possible, pulling out the arrow. Several more hits demonstrated that a roving arrow would not hold, and also that the line would tangle as it uncoiled from the ground. The line was

then stretched straight over the arrow rest and behind the archer for about thirty feet. When the arrow was shot the line was caught before it ran out completely. This was tricky and resulted in a lost arrow.”

More R & D was obviously needed to improve their fishing set-up, so back to the drawing board they went. First, they looked at their arrow points, eventually making “two-bladed fish heads” and fitting them to their shafts. The author doesn’t give us any details as to

what they might have looked like, but it’s probably safe to assume that they resembled conventional broadheads. They also made a first attempt at a primitive line-holder, but neither it nor the special heads gave the desired results when a couple of the boys put them to the test a few days later:

“The reel fouled up and proved entirely unsatisfactory. Although we had about fifty shots we hit only five carp and managed to land only two of them. We discovered that when a hit is made near the edge of the body, a two-bladed arrow tended to cut a gash clear to the edge releasing the arrow. Also the record of clean misses was out of line with the hits we had secured when we used roving arrows.”

To get to the bottom of this latest problem, the author stationed himself on a bridge while Nate shot at a weed directly underneath him. The reason for the misses then became apparent.

“When the two bladed arrow head hit the water it would deflect from the line of flight by as much as eighty degrees and the direction of the deflection varied with every shot depending upon the way the flat of the head hit the water,” Dinerstein reported. “A few shots went straight, but very few. We tried out a Bod-Kin and the arrow flew straight.”

Refinements in the tackle continued that evening at the Bowfishing Gear Development Lab. Several of the archers fitted Bod-Kins onto their arrow shafts and filed the backs back into barbs. Then they drilled holes through the ferrules for tying on the line.

A simple bowfishing reel.

“At this point one of the boys had a brainstorm which resulted in the simple reel shown on the drawing. It was made from a thirteen inch length of 3/8th copper tubing. This was bent into the shape shown in the accompanying sketch and the ends were flattened out by squeezing in a vice. The reel was fastened to the upper limb of the bow.”

The next day after work several of the inventors went down to the lake to try out their new equipment and found that the changes were a vast improvement over the old tackle.

“I don’t remember who was the first to land a carp, but when the arrow hit, the fish seemed to go crazy. He broke water and put up a stiff fight, but the Bod-Kin held and he was soon brought to shore.”

However encouraging the success though, a couple of remaining problems still needed some attention. When old silver-scales got up a head of steam after being skewered and plowed through a weed bed like a runaway truck, the cedar shaft almost always broke. Fletching was another shortcoming. Once an arrow was shot, the feathers loaded up with water. The feathers also acted as a brake, limiting the arrow’s penetration.

The novice bow-fishermen solved the first dilemma by switching from a wood arrow to a 5/16-inch aluminum shaft “about eight inches longer than normal.” The troublesome feathers proved unnecessary after they found that the heavier arrow would fly true for up to 40 feet with no fletching whatsoever.

Only one refinement remained to be worked out, and that was in the line. Linen became too heavy when wet, so they switched to nylon fly line. With that last problem solved, their tackle had all finally come together—arrow, line, head, and reel—and the crew got down to some serious fish harvesting. Sam enthusiastically described the newfound thrills of bowfishing as follows:

“The arrow disappears under the water and the slack in the line sort of floats in the air for a moment. Then it suddenly darts to one side. Well, no one has to tell you that you connected. The carp breaks water whereupon it is possible to see the shaft embedded in the hump of the back. Right now is the time to grab the line and play Mr. Fish. Anyone who tried to horse them in, that means yank on the line with brute strength, is going to learn to be gentle or get a new line.

“No, sir, the fun is with the light line and careful handling. We did plenty of business that day and many days since then. We would usually wind up with fifteen or twenty pounds of fish to give away to the people who ate carp.”

Besides Sam Dinerstein’s account, other articles on bowfishing also began to pop up in archery magazines around that time, and in reading them it becomes evident that the wheel was reinvented numerous times by many other archers. The trial and error approach of those early enthusiasts on the cutting edge of the new sport called “bowfishing” was typical of archery at a time when bowmen were still developing the equipment and techniques for hunting all types of game.

What a great read!..Very historical..necessity is definitely the mother of invention ..more please!