In the fall of 1994, I received a phone call out of the blue from a man who identified himself as Dick in a rich Texas drawl that reminded me of my own parents, who had deep roots in the Lone Star State. He explained that he was in the area with family and friends hunting upland game, was aware of my own background in bowhunting, and thought I might like to meet his father. Uncertain of the direction in which this conversation might be headed, I politely asked who his father might be.

When he told me that his dad was Bill Negley, I nearly dropped the phone. By coincidence, I had recently read Bill’s Archer in Africa and watched the companion film, Moments of Truth. I enthusiastically accepted the invitation, and the next morning I was hunting pheasants with one of the most remarkable bowhunters I’ve ever met. My Lab even managed to eat the first rooster Bill dropped. Both generations of Negleys went on to become fast friends.

Fast forward to the spring of 2018, when I received—again out of the blue—a package from San Antonio bowhunter Zan Christensen. We had met before at the 2004 PBS Banquet in San Antonio, to which I brought Bill as a guest so this bowhunting icon could receive a few of the plaudits he never sought and seldom received from the bowhunting community. It turned out that Zan, an admirer of Bill, had done a series of interviews with him ten years previously, after which writer Roy Marlow inadvertently “scooped” him with a profile of Bill done for this magazine (see TBM, April/May 2008). Otherwise, Bill’s remarkable story has largely gone untold.

The package from Zan included recordings of those interviews and provided me with additional insights into a bowhunting figure I already thought I knew well. Some great original photographs accompanied these interviews. Not everyone deserves more than one profile in the same magazine, but Bill does, especially after the passage of time. What follows is derived from my own knowledge of Bill, his book and film, and the hard work Zan Christensen devoted to recording Bill’s story straight from the source, for which we can’t thank him enough.

Birth of a Bowhunter

Born in San Antonio in 1914, Bill Negley came from a long line of prominent Texans. (Although formal journalism standards suggest otherwise, I’ll often identify our subject as “Bill” just because that’s what I always called him.) His great, great grandfather, Gen. Edward Burleson, was the first Vice-President of the Republic of Texas, serving under Sam Houston. Bill credits his own father, Richard Negley, with introducing him to hunting at an early age by taking him dove shooting. Bill was always modestly proud of his wing-shooting skills, which I can confirm by personal observation. After obtaining a law degree from the University of Texas, Bill went on to a long, successful career with Standard Oil, over-seeing operations both in the United States and Venezuela, where he became fluent in Spanish.

Born in San Antonio in 1914, Bill Negley came from a long line of prominent Texans. (Although formal journalism standards suggest otherwise, I’ll often identify our subject as “Bill” just because that’s what I always called him.) His great, great grandfather, Gen. Edward Burleson, was the first Vice-President of the Republic of Texas, serving under Sam Houston. Bill credits his own father, Richard Negley, with introducing him to hunting at an early age by taking him dove shooting. Bill was always modestly proud of his wing-shooting skills, which I can confirm by personal observation. After obtaining a law degree from the University of Texas, Bill went on to a long, successful career with Standard Oil, over-seeing operations both in the United States and Venezuela, where he became fluent in Spanish.

Bill’s interest in bowhunting began in the 1950s as a result of a rifle safari in Africa during which fifteen rounds of ammunition left him with fourteen dead antelope of various species and one dead lion, an experience he described as “unfair to the animals and unrewarding to me.” Bear in mind that bowhunting was still a relatively new concept then, with few of the vast learning resources available to novices today. When he learned of a friend who had killed a whitetail with a bow, he became intrigued and bought a 65# recurve from Abercrombie and Fitch in New York City—along with a box of arrows totally mismatched to the bow.

Unsurprisingly, he was unable to hit anything. Finally, Arch Gassman, an experienced local archer, examined his tackle and explained the problem. Bill wound up with a 55# Damon Howatt and some arrows that matched the bow and began to hunt deer.

One Wager, Two Elephants

In 1956, Bill was visiting with other members of the American International Tuna Team in the Bahamas. A teammate named Bill Carpenter had just returned from an African safari during which he had camped near Howard Hill while Hill was filming Tembo. Carpenter expressed skepticism about the idea of killing an elephant with a bow, and before long Carpenter had given Bill ten to one odds against his own $10,000 (in 1956 dollars) that Bill couldn’t do it. Always a sporting man up to a challenge, Bill accepted.

He then went straight to the top of the small American bowhunting community by making a call to Fred Bear, describing his intentions, and soliciting Bear’s help. This resulted in a series of increasingly heavy custom Bear bows, advancing in 10# increments until Bill received a #102 recurve from Bear and started training with it. In early 1957, Bill finally departed for what was then the Belgian Congo by way of London and Nairobi amidst a flurry of generally favorable press coverage. Word of the bet had gotten out, arousing intense public interest. Given the public relations fiasco the “Cecil the Lion” incident recently generated for hunting, it’s hard to realize that just sixty years earlier the world was cheering for an American hunter intent on killing an elephant with a bow. How times change.

Negley’s mission was not without controversy within the bowhunting community however, and some of that controversy persists today. By this time, Tembo had been released and Hill had represented himself as the first man to kill an elephant with a bow. Hill’s photographers, however, did not share Hill’s teetotaling habits and had been frequent after-hours visitors to Bill Carpenter’s African camp, which kept a robust supply of alcohol on hand. They told Carpenter’s party that Hill’s PH (professional hunter) had shot the elephant in the knee before Hill drew his bow, in order to keep it within range of the cameras.

Personally, Bill respected Hill, calling him “undoubtedly the ablest archer and bowhunter the world has ever known” and selecting his classic broadhead design rather than Bear’s to carry on his elephant hunt. However, he believed the story of the rifle shot and felt that this disqualified Hill’s elephant as a bow kill—an attitude toward firearms on bowhunts for dangerous game that would play out even further during his own African hunting career. A certain amount of ill-will eventually developed between Hill and Negley over the matter, and Bill eventually chose different broadheads for his subsequent hunts.

Personally, Bill respected Hill, calling him “undoubtedly the ablest archer and bowhunter the world has ever known” and selecting his classic broadhead design rather than Bear’s to carry on his elephant hunt. However, he believed the story of the rifle shot and felt that this disqualified Hill’s elephant as a bow kill—an attitude toward firearms on bowhunts for dangerous game that would play out even further during his own African hunting career. A certain amount of ill-will eventually developed between Hill and Negley over the matter, and Bill eventually chose different broadheads for his subsequent hunts.

Let me now interject a brief editorial comment prior to any hate mail. Howard Hill fans tend to be extremely devoted to their hero, with good reason. Neither I nor the magazine take any position on the legitimacy of Hill’s elephant above and beyond reporting what Negley and others have had to say about the subject. Those who believe otherwise are free to do so. End of discussion.

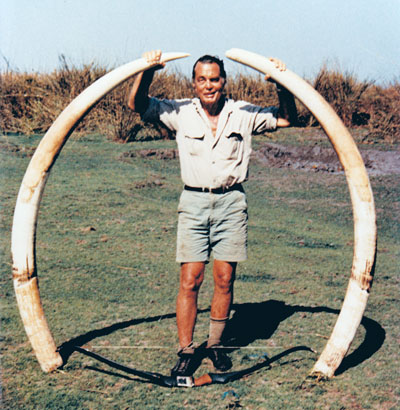

In February 1957, Bill arrived in the Congo with PH Eric Rundgren, his camp crew, photographers co-sponsored by Fred Bear, and a pair of highly capable Native trackers whose skills would prove crucial in the days ahead. Bill had just one goal in mind on that trip: winning his by then well-publicized bet with Bill Carpenter by killing an elephant with his bow and no interference from a firearm. Remarkably, he accomplished this goal not once but twice in two days of hunting. (His license allowed him two elephants—and cost him the grand sum of $250!) Bill ably recounts details of these hunts in Chapter Five of Archer in Africa.

Several points of interest emerge from those accounts. While Bill was a capable and courageous hunter he was not a particularly good archer, and to his credit he was always honest about his shooting. He hit his first elephant too far back, as PH Rundgren was quick to point out repeatedly, to Bill’s irritation. The arrow did a lot of damage despite the poor placement, and Bill was able to finish it off with no firearm assistance. Similar events occurred with the second elephant, which also required several hours and another great performance by the trackers, who always received due credit from Bill for their skill and determination.

In both cases, the problems arose from poor shooting rather than poor performance by his tackle, as Bill openly admits. While he was hunting with Hill broadheads, his shafts came from Fred Bear who understood the importance of heavy arrows on thick-skinned, heavy-boned game like elephants. Bear had supplied Bill with two kinds of shafts, Forgewood and custom aluminum. Both were heavy, although I’ve never determined exact weights. On those two elephants, most shots penetrated up to the fletching.

Bill returned home to considerable fanfare (most of which he tried to avoid), including a few derogatory notes from rabid anti-hunters proving that the “Cecil” uproar isn’t an entirely modern phenomenon. He had won his bet and donated the proceeds to charity. Now he would lay the bow aside for nine years before returning to Africa with an even more challenging ambition: to take all of the continent’s Big Five dangerous game animals (elephant, rhino, Cape buffalo, lion, and leopard) with the bow—and no firearm backup at all.

Big Five

Once again external factors and a competitive nature fueled Bill’s interest in returning to Africa in the 1960s. Bill enjoyed challenges and liked to be the first to accomplish difficult goals, as had been the case with Hill’s disputed elephant. By 1964, Bob Swinehart was one lion and one rhino short of being the first bowhunter to take the Big Five, and his efforts were drawing a lot of attention. Again, Negley wanted to be the first one to the top of the mountain.

Bill had done a lot of thinking by then and had reached the conclusion that you weren’t really bowhunting dangerous game unless you faced the danger without a rifle behind you. He made this plain as he started to plan his delayed return to Africa, and needless to say he had trouble finding a reputable PH who would agree to those terms. With two elephants under his belt already, “all” he needed to complete the mission was a leopard, lion, buffalo, and rhino. Furthermore (Bill never seemed able to resist the impulse to make hard things harder) he decided he wasn’t going to settle for the relatively docile white rhino, which he was familiar with from earlier trips. His would have to be a smaller but much more aggressive and dangerous black rhino, and they were already growing scarce everywhere they once roamed in abundance. (Today, black rhino hunting is completely banned throughout Africa.)

Bill had done a lot of thinking by then and had reached the conclusion that you weren’t really bowhunting dangerous game unless you faced the danger without a rifle behind you. He made this plain as he started to plan his delayed return to Africa, and needless to say he had trouble finding a reputable PH who would agree to those terms. With two elephants under his belt already, “all” he needed to complete the mission was a leopard, lion, buffalo, and rhino. Furthermore (Bill never seemed able to resist the impulse to make hard things harder) he decided he wasn’t going to settle for the relatively docile white rhino, which he was familiar with from earlier trips. His would have to be a smaller but much more aggressive and dangerous black rhino, and they were already growing scarce everywhere they once roamed in abundance. (Today, black rhino hunting is completely banned throughout Africa.)

He finally made contact with PH Jorge Alves de Lima, who hunted in Angola and Mozambique, both still Portuguese colonies at the time. De Lima somewhat reluctantly agreed to Negley’s terms. At age 52, Bill met de Lima in Angola, with a black rhino his main priority. The two of them agreed to keep de Lima’s .468 H&H cased, unloaded, and disassembled in the vehicle, and never within 100 yards of the hunter during a stalk. Once again, a professional photography crew accompanied the expedition (although Negley would eventually be disappointed with the quality of the film).

In early October, they cut a fresh rhino track and began to follow it. Several hours later the trackers spotted the animal bedded down and Bill made a slow, cautious approach to twenty yards before sending a heavy aluminum arrow crashing into its side. As with his first elephant the shot placement was a little far back, although the penetration was solid. Nonetheless, it took the team the rest of the day, two more stalks, and another remarkable performance by the two trackers before Bill could slip in and finish the wounded rhino.

Although he had taken a rhino with his bow and no assistance from a firearm, Bill was openly troubled by his inability to kill the animal cleanly and was also disappointed by the quality of the film. He eventually atoned for these missteps on a subsequent hunt in a neighboring area of Angola, when he stalked within twenty-five yards of another sleeping bull rhino that only lasted thirty seconds after a perfect arrow through the chest.

Physically, the leopard may be the most reasonable bowhunting quarry of any of the Big Five species, but Bill, who didn’t enjoy sitting over bait, never devoted much time to hunting them. He did kill one however, shortly after he took his first Angola rhino. He wasn’t very proud of it though, as it was a small cat and he shot it from the back of the safari vehicle when they encountered it more or less by accident. Although this was a required step on the path to his Big Five, he would never discuss his leopard with me, and he devotes less than a page to the subject in Archer in Africa. Bill later admitted that, “The leopard was so unimpressive that I refuse to publish its photograph.” Indeed, I’ve never seen one.

The dead leopard left Negley facing the Cape buffalo and lion in his quest for the Big Five, and he wasted little time getting after them. The buffalo hunting required them to wade across a river at first light, pick up a promising track, and follow it. While they had no trouble locating fresh tracks, they always led into dense thorn brush where quiet stalking proved extremely difficult. After many frustrating days of spooked buffalo at close range with no shot opportunities, Bill finally spotted two bulls bedded down in a position that offered a favorable stalk. He closed the distance successfully, shot one of the bulls in its bed, and watched it drop. As sometimes happens when bowhunting, when everything goes right it can actually seem easy. Now it was time for a lion.

The dead leopard left Negley facing the Cape buffalo and lion in his quest for the Big Five, and he wasted little time getting after them. The buffalo hunting required them to wade across a river at first light, pick up a promising track, and follow it. While they had no trouble locating fresh tracks, they always led into dense thorn brush where quiet stalking proved extremely difficult. After many frustrating days of spooked buffalo at close range with no shot opportunities, Bill finally spotted two bulls bedded down in a position that offered a favorable stalk. He closed the distance successfully, shot one of the bulls in its bed, and watched it drop. As sometimes happens when bowhunting, when everything goes right it can actually seem easy. Now it was time for a lion.

The team had actually spent some time hunting lions at the beginning of the safari, before Bill killed the rhino. These efforts included an exception to Bill’s usual hunting methods: the presence of a firearm, in this case a shotgun loaded with buckshot. They made this concession because they anticipated being very close to lions, and events validated their concerns. Although they never had to fire the shotgun (and Bill never took a shot with his bow), they had several encounters with two big male lions at terrifyingly close distances, as recounted in detail in Archer in Africa.

After the clean kill on the buffalo, they devoted all their efforts to hunting lions. They abandoned pursuit of the two big males on the grounds that those cats had grown too wary to approach within bow range after all of their previous encounters. On the last day of October, they lured a large lioness in to a bait and Bill shot an arrow completely through its chest. The big cat dropped in sight, much to the eventual delight of the local villagers, who always regarded lions as the most dangerous animals in the area. With that shot, Bill Negley completed his quest for the Big Five.

However, Bill’s natural competitiveness—he himself went so far as to describe it as “vanity”—suffered a blow when he returned to civilization and learned that Bob Swinehart had successfully completed his own Big Five as Negley was headed into the bush. This information confirmed that Bill was not the first to do so after all, but the second. For years, he graciously acknowledged this fact despite the disappointment it caused him. Then a chance 1983 meeting in San Antonio called the whole issue into question again, when Negley ran into a young Portuguese PH named Adelino Pires who reported that he had been a junior hunter in Mozambique with Swinehart when he shot his elephant. According to Pires, Swinehart’s elephant, like Hill’s, had been shot in the knee with a rifle before the bow came into play. By this time Swinehart had died tragically, and Negley never had an opportunity to discuss the matter with him.

Closing Thoughts

Bill Negley did make several return trips to Africa, as well as a venture to the Arctic during which he took a polar bear after a harrowing close-range encounter. Space precludes relating all those adventures here. The best I can do is encourage interested readers to watch Moments of Truth or track down a used copy of Archer in Africa. The book was published in a limited edition by Amwell Press in 1989, and copies have become valued collectors’ items. Used copies are available on-line, but don’t expect any bargains. My personally autographed copy is one of the most treasured items in my extensive collection of books authored and signed by friends.

Despite the elements of adventure, courage, and drama that characterize Bill’s bowhunting accomplishments, it’s clear that he was not a particularly good shot despite a rigorous training schedule that he adhered to strictly. Having worked myself up to a 90# bow prior to a buffalo hunt (before I realized that all that draw weight wasn’t necessary), I can sympathize with the difficulty of shooting a heavy bow accurately under stressful conditions in the field. To Bill’s credit, he never tried to sugar-coat his bad shots or make excuses. On one of his later safaris, he cheerfully admits a clean miss on an elephant at ten yards.

Bill was also generous about sharing credit whenever appropriate, especially with regard to his Native trackers—Duo and Kaveca on his first elephant hunt, and Melasa and Samuondo during his quest for the Big Five. He expresses similar admiration for his first two PHs, Rundgren and de Lima. When he experienced disappointment with his PHs and trackers on subsequent safaris, he was candid about that as well.

After years of friendship, I have nothing but respect for Bill as a gentleman and a bowhunter, and I miss him. However, it should be obvious that we were different people who approached bowhunting in different ways. I’ve never felt the competitiveness that motivated Bill, and I’ve always declined opportunities to get drawn into some of the discussions it aroused even though I have no reason to doubt Bill’s version of events.

There was another side to Bill’s personality that few hunters ever saw. A natural charmer and ladies’ man, Bill was innocently (I hope) enamored of my mom, who regularly participated in our annual bird hunts. Whenever we all gathered for dinner at the end of the day, Bill’s friends would secretly place bets as to how long it would take Bill to remind my mom that he had served as captain of the American International Tuna Team. The snickering often became so loud that it was impossible to eat.

Who killed the first “clean” elephant with a bow, Hill or Negley? Who took the first honest Big Five, Negley or Swinehart? I don’t really know, and I don’t really care. I do know that all three were brave, capable hunters who each broke new ground for bowhunting in his own unique way. That’s good enough for me.

Author’s note: Once again, on behalf of the magazine I wish to thank Zan Christensen for the effort he invested in obtaining information from Bill Negley and sharing it with TBM readers.

An alternative view of the race for the Big Five can be read in Greg Ragan’s article Big Five—The Elephant in the Room

Leave A Comment