Should I or shouldn’t I? The question kept tumbling through my head. For the last five months I had been hosting a colleague and fellow biologist from Beijing, Dr. Jiliang Xu and it was now almost time for his return to China. Jiliang is a game bird biologist and teaches wildlife management courses at a Chinese university, but had virtually no exposure to hunting, let alone bowhunting for big game. I was concerned about inviting him to our elk camp because I did not know if he would enjoy the adventure or in some fashion be offended by our attempts to harvest game animals, especially with rather primitive traditional archery equipment. Jiliang had spent a fair bit of time in the field with me trapping everything from sage-grouse to pelicans and I knew he was no lightweight when it came to the outdoors. Still, he lived in the middle of one of the world’s largest cities and hunting is not a pastime embraced in general by Chinese culture. His English was far, far better than my Chinese (I can say hello and thank you) but things did tend to get lost in translation. In no way did I want to put my Chinese guest in an uncomfortable spot. So, should I or shouldn’t I extend an invitation to elk camp? The thought of an unintentional faux pas made me nervous.

After a great deal of deliberation, I decided that since he was a wildlife professional, he should be at least given the opportunity to experience hunting. I talked it over with Hub Quade, my elk hunting partner, to make sure he had no objections. Hub seemed to think it was a very good idea so I asked Jiliang if he would like to spend three days at our elk camp, and become acquainted with both bowhunting and bird hunting. He accepted without any hesitation.

I picked Jiliang up at his apartment on a warm September morning and we set off on the two hour trip to elk camp. On the drive, I tried to explain our approach to big game hunting, including the difference between compound bows and traditional archery tackle and my preference for keeping things simple. Shortly after his arrival in the U.S., Jiliang had attended an archery tournament with me, so he had some knowledge of recurves and longbows, but appeared very vague on how someone might actually get close enough to a real live animal and harvest it with that kind of equipment. He also had been around my bird dogs, but had no idea how they found and pointed birds. This was going to be an interesting trip!

I picked Jiliang up at his apartment on a warm September morning and we set off on the two hour trip to elk camp. On the drive, I tried to explain our approach to big game hunting, including the difference between compound bows and traditional archery tackle and my preference for keeping things simple. Shortly after his arrival in the U.S., Jiliang had attended an archery tournament with me, so he had some knowledge of recurves and longbows, but appeared very vague on how someone might actually get close enough to a real live animal and harvest it with that kind of equipment. He also had been around my bird dogs, but had no idea how they found and pointed birds. This was going to be an interesting trip!

We arrived mid-afternoon, early enough to stow our gear and get in an evening hunt. I explained the general approach to hunting with a stick bow to Jiliang, outfitted him with a camo shirt, and we headed out in search of deer and elk. We had gone no more than 100 yards when I noticed my companion’s approach to hunting was exactly the same as his approach to conducting field research. He just assumed we had to get from point A to point B in the most efficient manner possible, so he put his head down and marched up the hill. A couple of times I stopped him and explained the importance of going slow, being quiet, and looking around. Remember the language issue. The second time I stopped him I pointed out a doe mule deer that he had walked right by without seeing.

Jiliang was a fast learner and about 10 minutes after passing the doe I felt his hand on my arm. I stopped and he was pointing to a doe and fawn about 25 yards away that were watching our approach. We did not see any elk on that evening hunt but did hear some bugling in the distance and managed to flush a couple of ruffed grouse. I also pointed out one of our treestands, explained its use, and showed Jiliang a couple of elk wallows. As the sun was setting and we made our way back to camp Jiliang appeared to be having a good time.

Hub and I maintain a pretty versatile bowhunting camp that normally includes a few flyfishing excursions and some bird hunting. So, the next morning we planned to take Jiliang bird hunting. If all went well, this was going to be his first exposure to game actually being taken. And things did go well. We were after sage grouse and travelled to a high mountain sagebrush-covered bench about a forty minute drive from our camp. Within a half hour or so of hunting we had seen 50 or more sage grouse. Unfortunately my young pointer was more interested in chasing jackrabbits and flushing grouse than hunting and pointing birds. So, I had to explain to my friend from Beijing that yes, I could have shot a bird out of the first few groups of grouse, but there was no point to it. Hunting was much more than just killing something. As Jiliang gazed out over the upper Snake River Plain from our high perch, he seemed to understand. We moved on in search of smaller flocks and singles that might hold a bit better for the dog. Soon we were rewarded. My pup made a beautiful point and I managed to make a decent shot, despite having an audience. After the retrieve I showed Jiliang how to field dress the bird and we spent some time praising the dog, taking photos, and admiring the grouse. By this time we were a long way from a road and an even longer way from the truck. It was time to head back because we were planning to bowhunt later in the afternoon. After linking up with Hub at the truck we watered the dogs, again admired our morning’s bag, and headed back to camp for lunch and the afternoon hunt. On the way back Jiliang seemed animated by our morning efforts. He had never been hunting before and the only thing he knew about hunting was what he had read in text books. He was now getting a hands-on education. In a sense, we were teaching the teacher.

Hub and I maintain a pretty versatile bowhunting camp that normally includes a few flyfishing excursions and some bird hunting. So, the next morning we planned to take Jiliang bird hunting. If all went well, this was going to be his first exposure to game actually being taken. And things did go well. We were after sage grouse and travelled to a high mountain sagebrush-covered bench about a forty minute drive from our camp. Within a half hour or so of hunting we had seen 50 or more sage grouse. Unfortunately my young pointer was more interested in chasing jackrabbits and flushing grouse than hunting and pointing birds. So, I had to explain to my friend from Beijing that yes, I could have shot a bird out of the first few groups of grouse, but there was no point to it. Hunting was much more than just killing something. As Jiliang gazed out over the upper Snake River Plain from our high perch, he seemed to understand. We moved on in search of smaller flocks and singles that might hold a bit better for the dog. Soon we were rewarded. My pup made a beautiful point and I managed to make a decent shot, despite having an audience. After the retrieve I showed Jiliang how to field dress the bird and we spent some time praising the dog, taking photos, and admiring the grouse. By this time we were a long way from a road and an even longer way from the truck. It was time to head back because we were planning to bowhunt later in the afternoon. After linking up with Hub at the truck we watered the dogs, again admired our morning’s bag, and headed back to camp for lunch and the afternoon hunt. On the way back Jiliang seemed animated by our morning efforts. He had never been hunting before and the only thing he knew about hunting was what he had read in text books. He was now getting a hands-on education. In a sense, we were teaching the teacher.

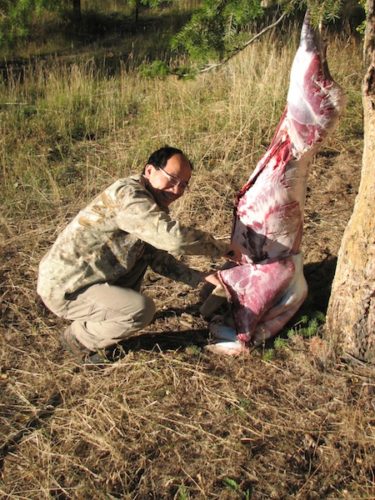

Late that afternoon we decided to send Jiliang with Hub to listen to elk bugling and retrieve a treestand. Hub had already arrowed a nice six-point bull, so he volunteered to take Jiliang up the mountain. I headed off in a different direction to an area where I had been seeing a number of deer. Deer were plentiful and I thought with a little good fortune I might be able to shoot one while Jiliang was in camp. I had not walked more than 20 minutes from camp when luck was with me and I spied a doe bedded down on the other side of a small quaking aspen patch. I eased toward the deer, found a hole through the quakies, and made the shot. The deer bolted but my shot felt good. I waited a bit then walked over to where it had been bedded. A brief search showed a large splash of blood, so I sat down to wait. After a half hour passed I began to follow the blood trail and 10 minutes later was standing over the doe.

It took me about an hour to get the deer back to camp. As I reached camp I could hear Jiliang and Hub talking as they returned from their little jaunt. This was it. What would my friend from Beijing think of the deer I was hanging in camp? My friend who had never been exposed to hunting and lived a very urban life had seemed to really enjoy the bird hunting early in the day. But a deer might be a different matter and I was still a bit nervous about offending my new friend or putting him in an uncomfortable spot.

It took me about an hour to get the deer back to camp. As I reached camp I could hear Jiliang and Hub talking as they returned from their little jaunt. This was it. What would my friend from Beijing think of the deer I was hanging in camp? My friend who had never been exposed to hunting and lived a very urban life had seemed to really enjoy the bird hunting early in the day. But a deer might be a different matter and I was still a bit nervous about offending my new friend or putting him in an uncomfortable spot.

The two came into camp excited from the bugling they had just experienced and exhilarated by a hike up the mountain. Both men stopped when they saw the deer and I noticed Jiliang’s eyes widen. Then a big smile creased his face and my worries were over. A successful hunt and Jiliang was just as thrilled with the outcome as I was. Jiliang’s enthusiasm was genuine and he even pitched in to skin the deer. During this one day, Jiliang had seen about fifty sage grouse, several herds of pronghorn antelope, a few jackrabbits, two golden eagles, a moose, and a coyote, listened to elk bugling, and helped skin a deer. Not your routine day in downtown Beijing! He enjoyed a bounty of new outdoor experiences associated with traditional bowhunting and his smile did not fade all evening. I was surprised that someone from a big city half way around the world could develop such an apparent deep appreciation for bowhunting in a short period of time. Then again, given the mountains, forests with their golden quaking aspens, haunting bugle of an elk, and the fine lines of a stick bow…yeah, ok, I shouldn’t have been surprised! More than that, bowhunting and the use of wildlife resources represent a past that is shared by virtually all cultures throughout the world, though many are generations removed from this activity. Jiliang’s response may simply indicate how close to the surface these ancient activities still are. Perhaps it only takes a small experience to reawaken interest in hunting and rekindle the bow hunting flame, regardless of one’s cultural or ethnic background. Jiliang has returned to his work and family in Beijing but I hear from him often. I won’t be surprised at all if we share a bow hunting camp again.

Author’s biography: Jack Connelly is a biologist for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, specializing in game bird research. He lives in Blackfoot, Idaho with his wife Cheryl and their four bird dogs.

Equipment note: On this hunt the author used a 54″, 55# Fox recurve, Traditional Only shafts, and 2-blade Magnus broadheads.

Leave A Comment