In 1955, Roy Hoff, the editor of Archery Magazine, took a trip to the Alaska tundra. It was the kind of expedition every bowhunter dreams of—pursuing big game in Alaska, a place which he describes as “that fabulous wonderland where wildlife is so plentiful that to bag a few nice trophies is as easy as falling off a log.”

Until then, however, a major problem stood in the way of such a trip. The Alaska Game Commission held a dim view of bowhunting, and there were laws that prohibited it anywhere in the territory.

“When Art Young and other world famous expert big game bow and arrow hunters successfully bagged grizzly and Kodiak bear in Alaska,” Hoff explains, “they unknowingly and, of course, unintentionally set the stage for subsequent tragic events. Other hunters, with a limited knowledge of hunting with a bow, and no experience in hunting such ferocious animals, figured that to bag a grizzly or Kodiak would be just a breeze. One party had to learn the hard way. In a scuffle with one of these big brutes, one member of the party lost his life and some other members were mauled so badly they barely escaped with their lives.”

After that bloody maiming melee, the Game Commission declared that there would be no repeat performances, and simply banned the bow. In response to archery’s growing popularity though, in 1954 they relented. While reinstating bowhunting for most game, they still prohibited its use on the big bruins.

With the general ban lifted, archers were quick to respond. Hoff and his bowhunting wife, Frieda, along with a couple of California archery notables, “Wild Bill” Childs and Tim Meigs, made a trip the following year for a piece of the action.

Upon their arrival in Anchorage, they were greeted by a gang of Alaskan bowhunters, who took them to their hotel. The number of saloons along the way impressed Hoff, but the number of cars driving around town with moose on them impressed him even more.

“It was not an uncommon sight,” he reported, “to see a car driving up the street in Anchorage adorned with moose antlers on which were draped bows and arrows, and, after a mad rush to overtake the driver, we became accustomed to greeting the smiling bow hunter blood-stained to the elbows and the car springs sagging under the weight of a thousand pounds of moose meat.”

Early the next morning the party met their guides who packed their duffel on a couple of horses, and the party started the seven-mile trip to camp. When they got there, they found a “camp meat” moose already hanging.

It seems that the week before the visiting bowmen arrived, guides M.M. Moore and Ivan Blood were setting up tents and getting things ready. Even though they weren’t hunting, they had their bows along “just in case” and were not adverse to taking a few minutes off now and then to glass the surrounding hillsides in order to keep an eye on things. Sure enough! They spotted a big bull browsing, did a sneak on it, and loosed their arrows together. Either shot would have proven fatal.

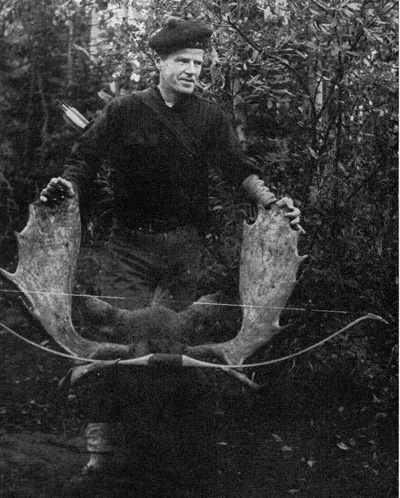

Charlie MacInnes, well-known Alaska bowman, inaugurated the legalizing of big game bow and arrow hunting in Alaska by downing this huge bull moose near Anchorage. One arrow, through both lungs, did the trick in thirty seconds.

But while the easy taking of this animal seemed a harbinger of success, the area proved to be devoid of moose. After rainy weather dampened their hunting three days in a row, the party returned to Anchorage to regroup and dry out. When they got there, they headed over to the Northern Sporting Goods store—headquarters for local moose hunters—and ran into one of the area’s most popular and successful archers, Charlie MacInnes. Charlie was smeared with blood, which prompted Hoff and company to ask simply: “Where is he, Charlie?”

MacInnes had a reputation as something of a character. Intensely proud of his Scottish heritage, he did all of his hunting wearing a kilt. But besides its symbolism, there was another, more practical, explanation for this choice—the short length of the lower garment allowed for much quieter walking and stalking.

One arrow proved to be enough for Charlie’s moose. As he hunted around Goose Lake he’d sighted a big bull headed his way. When it had closed the distance to about forty paces it stopped, evidently having sensed the hunter’s presence. At that point Charlie loosed an arrow, which struck the animal in the boiler room.

“The bull whirled and dashed off down the slope. He disappeared in the brush for a few seconds, but I spotted him when he came out on the flats below. He stopped in the open spot and appeared to attempt to turn his head back in my direction. At that moment I heard the air go out of his lungs in one last breath and saw him collapse. It sounded a lot like letting the air out of a rubber mattress. I’d estimate that from the time the bull was hit until he keeled over dead was about fifteen seconds.”

Hoff and his party stayed in town for another day waiting for their guide to arrive and take them to caribou country, so they made a second trip to Northern Sporting to check on things. Sure enough. “While we were gone,” Hoff recounts, “another moose had been bagged.”

A bowhunter named Don Goodman had scoured the swamps for days without success, but on this particular morning he got lucky. He was traversing some muskeg on his way back to his car when a big bull got up from its bed in some tall grass twenty yards in front of him. Then it stood broadside, apparently unperturbed by the intrusion.

“I loosed a carefully-aimed broadhead and observed the feathers as they disappeared into the rib cage,” Goodman recounted. “I swear that this dumb moose never even so much as batted an eye.”

Another arrow followed, striking the beast not two inches from the first, which drew the same reaction.

The smiling archer is Bob Meyers, president of the Alaska Bowmen. Bob has reason to be happy…he brought down this bull moose with one arrow, shot from a 63# bow. Although antlers are comparatively small, the carcass yielded over 550 pounds of meat.

“The critter just shuffled his feet, stuck out his neck a little closer toward me and just glared. As I nocked the third arrow I looked around to see if there were a convenient tree I could climb or at least hide behind. There was none, so again I blazed away. By this time I was so dog-gone nervous and shaking so badly I hit him in the foot. By the time I loosed the fourth arrow I was a physical wreck and missed that big hulk completely.

“By now I was desperately praying for help – a fellow bowman, shotgun hunter, or maybe somebody with a club. As I fumbled for another arrow I stood transfixed by a sight I couldn’t believe. Just when I thought I was a gonner, over he went deadern’ a mackerel.”

The subsequent autopsy showed that the first two arrows (shot from a 75# bow) had penetrated completely and were sticking in the ground. Goodman concludes “If you can get one broadhead through the lungs of a moose you might just as well discontinue any further shooting and start reaching for your hunting knife. Within one minute—two or three at the most—you can start skinning.”

When the Hoff party’s caribou guide showed up, the group headed north. Since the country proved to be too rugged for horses they made the 50-mile trip by “swamp buggy”—an early all-terrain vehicle cobbled up with an assortment of parts including a Model A Ford engine sparked with a magneto ignition, airplane and earth mover tires, and plenty of heavy-duty steel pipe and plate. Evidently it got the job done, since Hoff writes:

“Many times on this trip up the Nelchina [river] the engine was almost entirely submerged. Actually we went through water holes so deep and over boulders so huge, it didn’t seem possible that a motor-driven vehicle short of an army tank could accomplish such a feat.”

This contrivance got them to their hunting camp in a mere eight and a half hours, but only after a bone-jarring trip. Without the benefit of any kind of suspension, Hoff likened the journey along the riverbank to “riding a Brahma bull bareback.”

As Hoff awoke at daybreak the following morning, the thought struck him that this camp might simply be another of those “dry holes.” Unlike moose, caribou are constantly on the move, so any area can be feast or famine. To add to his concern, on the trip into camp the previous day the hunters spotted only one animal.

These fears proved unfounded, though. Before the sun even poked up over the horizon the impatient Tim Meigs snuck up a cut bank only a few paces from camp. There he spotted eight caribou bulls within fifty yards.

“Every hunter,” Hoff writes, “immediately assumed the attitude of having just sat on a hot stove. Everybody grabbed his bow and quiver and scattered in every direction in the hope we could surround the herd and provide someone with an opportunity for a shot. Bill and Tim both were lucky. They both singled out a bull and in the cover of river-bottom willows, managed to stalk him within easy shooting range.”

Just as the two archers began to draw, though, they startled a near-by flock of ptarmigan, which took to the air. Because of the commotion, the caribou realized that something was up and spooked.

Hoff and Mert (another hunter who had joined the caribou party) were hanging back, and now decided to head in the opposite direction in case the animals circled. They traveled only about fifty yards when Hoff glanced toward camp and saw his wife frantically waving her arms and pointing up the river. The two hunters then headed in that direction, crested another hill and spotted eleven animals—mostly huge-antlered bulls—drinking out of a stream.

After a hasty conference the group decided that the best strategy would be the old “squeeze play” where the hunters would split up and make their approach in a pincer movement. That way if the animals spooked from one, they might blunder into the other. Unfortunately, before either of the archers could get into position the caribou spotted one (or both) of them and departed in a serene and orderly manner single file up the opposite hill.

The hunters stalked several more groups of caribou over the next few days, but each time the animals were one step ahead of Hoff and his friends. In frustration, a few of the archers turned their attention to ptarmigan, collecting enough for a banquet their last night in camp.

With three days left to hunt, a mass of cold air from the arctic descended on the camp. The temperature plunged to near zero and the river began to freeze up. The guides were concerned that the swamp buggies might have problems with snow and ice, and opted to get out while they could.

Although the hunters bagged no caribou during their stay, Hoff called the trip some of the “most fascinating hunting I have ever attempted”—no small accolade coming from a man who just finished a moose hunt in Alaska and stalked elk in Idaho, antelope in Wyoming, and deer over most of the rest of the “lower 48.”

Leave A Comment