Growing up with a 35-cent shotgun and a $35 motorcycle, he came to archery late, inspired by a film!

I remember him as engaging, cordial, mildly surprised, it seemed, by his own celebrity. “I’ve had more than my share of fun,” he admitted with a self-effacing grin. His humility endeared Fred Bear to just about everyone. By the time I met him, his business was hugely successful. He had not only sold a lot of archery tackle, but fundamentally changed the way bows were built. His field exploits had drawn millions of people to “the grey goose wing.”

The Thompson brothers, then Pope and Young and Compton, then Howard Hill and Ben Pearson, had contributed a great deal to the revival of target archery and the nascent sport of bowhunting. Between the Civil War and World War II, a handful of such enthusiasts made their own tackle and used it to extend the accepted limits of arrows on targets and game.

Fred Bear was born smack in the middle of this period. His father worked as a machinist for the Landis Tool Company in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. Aileen was the first of Harry and Florence Bear’s children. In March, 1902, evidently during a late blizzard, Frederick Bernard Bear was delivered at home. Another sister, Elizabeth, would follow. Fred’s paternal grandfather, Abner Bear, lived with his second wife in nearby Mechanicsburg. His sons, Harry and Charles, hadn’t taken to the stepmother, so they spent much of their youth with Abner’s unmarried Mennonite sisters, Sarah and “Lib.” Great-aunts to Fred and his siblings, they adored the children. When Fred was still a toddler, his parents moved from Waynesboro to Plainfield, just a mile from “the Aunts.” Harry worked at the Frog and Switch Manufacturing Company in Carlisle and saved enough money to set himself up in the chicken business. His father-in-law, George Drawbaugh, a carpenter, helped build the necessary structures.

Harry’s new enterprise failed. After three years he sold the chickens and facilities and moved his family to Elliotson. It was near enough to Sarah and Lib’s farm that both Harry and Fred, now nine, helped the Aunts with chores. One of Fred’s jobs was to tend, cut, and market an acre of asparagus. Harvest saw him hard pressed to keep up with the ripening crop. Well before daylight, he loaded fresh asparagus and other produce onto a horse-drawn wagon. After the drive to town, he manned the market stall, which sold out in a couple of hours. By noon Fred had arrived home, again unharnessed the horse, then wolfed lunch and headed for the field. When the Aunts moved to town later, Fred offered this service to a neighbor for 25 cents a day. He earned a bit more peddling dandelion greens from the stall for a nickel a bunch.

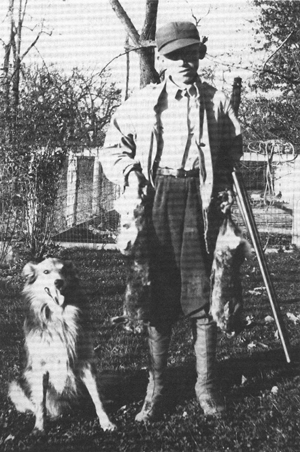

Twelve-year-old Fred Bear and his dog, Scot, after a successful day of rabbit hunting.

But produce was not Fred’s passion. He justified time in the woods by running a trap-line along nearby Conodoquinet Creek and its feeders. In an Old Town canoe, with his dog Scot, an ax, and a single-shot Stevens pistol, he serviced as many as 50 muskrat traps before school. Mink and skunks turned up on occasion and brought much more than the $2 to $3 fetched by rat pelts. Later, Fred took to capturing the skunks. He raised them in a chicken-wire skunk farm. His uncle Charley, who lived in New York, helped Fred market these and other trap-line bounty.

Fred’s education began at the rural, one-room Bear School, just half a mile from the farm. In sixth and seventh grades, he attended the two-room Plainfield School a mile away. But scholarship was hardly a priority. The lure of a life outdoors struck Fred early. By age seven, he was traipsing after his father on hunts for small game. Harry, who competed in offhand matches with a .32-40 target rifle (likely an 1885 Winchester Highwall) gave eight-year-old Fred a Quackenbush .22. The youngster’s wing-shooting career got off to a rocky start with the elder Bear’s muzzle-loading shotgun, bought for 35 cents at a farm auction. Fred slipped it out to kill a sparrow perched on a neighbor’s roof. The blast took a broad patch of slate with the bird. Harry was not pleased. Still, Fred soon got his own shotgun, a 12-bore L.C. Smith double.

At 13, Fred was old enough to join Harry and his deer-hunting group at their fall camp on South Mountain, about five miles from the farm. An old rail shack served as a lodge; they slept in bedrolls over corn stalks layered on the ground. Despite a chestnut blight that swept the area in 1915 and significantly reduced this food source for whitetails, Fred shot his first deer that year, with a Winchester lever-action rifle.

In 1918 the Bears left the farm and moved to Carlisle, selling the family automobile, a Maxwell, for $156. That money helped erase lingering debts from the chicken enterprise. But this new chapter in Fred’s life came with the loss of his sister Aileen, who’d succumbed in the influenza epidemic that year.

At age 16, after he’d abandoned his bicycle for a $35 Indian motorcycle, Fred asked his father for permission to join the Carlisle National Guard unit. Reluctantly Harry consented–on the condition that Fred replace his missing high school years with training in a trade. Fred’s time in the Guard included duty near Pittsburgh during the area’s ugly coalfield strike of 1922. When he returned, he was good to his word and started work in the drafting department at Carlisle Frog and Switch. Later he switched to the pattern shop and then worked, for 17 cents an hour, in the company’s foundry.

Meanwhile, Uncle Charley was tapping his resources to give Fred a boost. He’d given up trying to entice his nephew to join him in New York, where the smart, industrious (and ever single) Charley had prospered. He contacted a friend, Clarence Zahrant, in Detroit. Zahrant sold carpeting to the auto industry and quickly wrangled pattern-making work for Fred at the Packard Motor Company. Then he offered the young man an extra room in his home.

In 1923, the lanky 21-year-old high school drop-out moved to Michigan and threw himself into his new job. He soon completed classes for graduation credit and then took night courses in English, public speaking, and mathematics from the Detroit Institute of Technology. But the outdoors still had a grip. One autumn, he took unscheduled time off to join colleagues in deer camp. Consequently, he lost his job, but in short order he found a new one with Chrysler. Fred had already bought his own automobile, a Ford he named Henry. In a letter to Charley, he reported on its maiden road trip.

“… Burning out the brakes the first day [I installed] new ones at a cost of $1.59…. Expenditures on the car for the trip both ways amounted to $29 or $30 [which included] 62 gals. of gas, 4 qts. of oil, storage three nights….”

In 1926 Fred agreed to work for Clarence Zahrant, who’d started a tire-cover business. Two years later Zahrant sold out to Jansen Manufacturing Company, which also made golf bags. Fred stayed as plant manager, moving to share a house with friend Ray Stannard. In their spare time, the men built a couple of boats. The 15-foot, half-cabin crafts had oak keels and mahogany planking. Stannard equipped his with a 50-horse Johnson; Bear installed an experimental four-cylinder pancake engine. Both were christened and kept on the Fox River. Throttles came open on weekends over Lake St. Clair.

Though he’d made crude bows and arrows as a youngster, Fred became truly intrigued by archery when he and Ray saw a film at Detroit’s Adams Theatre. After that screening of the Alaskan adventures of Art Young, the young pattern-makers ordered lemonwood staves and birch dowels from Stemmler on Long Island. Wood-working came naturally; but bow tillering, matching arrow spine, and fletching shafts properly took weeks of trials on straw bales behind Stannard’s home – and much scrapped material.

Fred’s efforts proved timely. Not long after he and Ray had a few arrows flying straight, his boss, Mr. Jansen, invited him to a Rotary meeting. The guest speaker: Art Young! Fred, with his enthusiasm for archery and disarming manner, impressed Young. They made tackle together in Fred’s basement and shot arrows “roving” the hills on the outskirts of the city. Young passed along tips on bow-building that he’d learned from Will “Chief” Compton and regaled Fred with stories of their time afield with Saxton Pope, who had died in 1926. Art taught Fred how to fashion double-loop strings of Irish linen. Short years later, Young would leave Detroit for Homewood, Illinois, where he would die in 1935. But the seed had been planted.

In 1927 Fred married Ann Marie Thomas, a nurse. Marie would prove herself skilled with a bow in tournaments, and was always comfortable in the outdoors. Alas, differences emerged as Fred built his business. The union would last until 1945, ending in amicable divorce, with no children.

Fred Bear first hunted deer with a bow and arrow in 1929. He and two companions endured wet snow in a cedar swamp without skewering any venison. Fred recalled missing a snowshoe hare with his entire supply of six arrows, ringing the statue-still creature without touching … well, a hair. It would be another six seasons before he would arrow a deer. Meantime, he didn’t give up the rifle. In 1933 he killed his biggest buck, a 285-pound Michigan whitetail.

That year Fred’s life took a sharp turn when fire gobbled Jansen’s tire-cover plant. At the height of the Depression, recovery would not be quick. With Charles Piper (Stanley Jansen’s nephew), Fred scrounged $600 and bought a couple of used sewing machines, plus other tools. Under the shingle of Bear Products Company, in a garage on Tireman Avenue, the men started making advertising banners for Chrysler. Fred found room to build bows in a corner of the building. Two years later, when the business moved to bigger quarters, the bow-building bench followed. By 1939 Fred’s archery shop had become self-supporting, and the enterprises split. Charles Piper stayed at the tiller of Bear Products; Fred launched Bear Archery.

The May, 1941 issue of Ye Sylvan Archer announced the bow-building firm as set up for business at 2611 Philadelphia Avenue, Detroit. The new site was a former Maxwell garage, 6,000 square feet. Fred dedicated half the space to manufacturing, the rest to an indoor archery range. He shoe-horned an office into one side of the building, a retail counter into the other. First products included not only target bows of lemonwood, but leather goods such as shooting gloves and quivers. An Osage orange stave from Fred Kibbe of Coldwater became Fred’s first hunting bow. A longbow in profile, it had shorter, broader limbs.

Cavalry training with a National Guard unit gave Fred saddle time and horse sense that would later prove useful.

Faith in growing demand prompted Fred to hire salesmen to peddle Bear tackle to sport shops. With skilled bowyer Nels Grumley, he began making custom bows, which he sold for as much as $65. A new Detroit Archers Club (of which Fred was elected president) met at the Bear range. It established an outdoor range near Northwestern and Telegraph Roads, where Fred had flung arrows with Art Young. An early Club deer hunt drew 50 archers to St. Helen, near the Ogemaw Game Refuge. They shot one deer!

Another Club destination was Blaney, 30,000 acres of Upper Peninsula woodland. It was there, in 1935, that Fred arrowed his first whitetail, a spike buck. That year he also endured his first serious illness. The culprit, a hemorrhaging kidney, had to be removed. Two years later his remaining kidney would yield the same diagnosis. But in those days, without transplants, excising the organ was no option. A physician recommended drinking unsweetened grape-juice. The trouble went away.

While building bows, Fred Bear became archery’s ambassador. He helped establish bowhunting seasons in Wisconsin and Michigan, in 1934 and 1936. He carried that torch to tournaments too, attending a 1939 NAA event in San Francisco. Fred’s birth state of Pennsylvania soon embraced bowhunting. During this period, sportswriter Jack Van Coevering of the Detroit Free Press ran reports and photos promoting archery. In 1942 he joined Fred at Blaney to film a bowhunt for deer.

In those days, cameras were cumbersome, deer country untrammeled. And Fred Bear hunted from the ground, sneaking along trails rather than sitting in a tree. The first day of Van Coevering’s trip turned into long hours in tough weather. Fred fumbled an arrow to muff the only shot. Wrote Bear: “We had a long hike back to the car – hungry as wolves. We built a fire and toasted the sandwiches…. My hands were so cold I could hardly get my boots and wet socks off.” Then, two days later: success! The hunters spied a buck coming toward them at 30 yards. “In a split second he saw me and raised his head. I was not at full draw, but I had to shoot now or not at all…. The arrow, a large four-blade, struck the left chest …”

Van Coevering’s footage of this event was the first of 25 Fred Bear films that would appear over the next 40 years to introduce millions to bowhunting.

During the early 1940s Fred went farther afield for game, twice failing to claim a moose with an arrow. But the third try, in September, 1945, brought success. With his partner K.K. Knickerbocker, Bear drove to Duluth, crossing to Ontario at International Falls on the 17th. They motored north through heavy rain, and for three days hunted in wet weather. The 21st brought sun but no moose. Four days later, the hunters and their guides spotted a moose across a lake. Paddling furiously, Fred canoed to the far shore well in front of the bull. Splashing ashore, Bear readied his bow and slipped along a trail toward his quarry. “After a few anxious moments I heard him splashing and grunting…. Just that glimpse was worth the trip up here. The sun shining brightly on a set of antlers too big to even wish for…. The [shot alley] was narrow and the action fast as I drew back full length and drove a big four-blade head into the center of his rib section….”

Over the next decades, Fred Bear would travel to many foreign game fields, his natural charm and unabated enthusiasm for archery igniting worldwide interest in the bow. His exploits also generated new business. The company, ripe for expansion, drew capital from pals like Knickerbocker and Charles Piper, who sold Bear Products and invested the proceeds in Bear Archery. In April, 1947 that firm moved from Detroit north to Grayling, gateway to the Lower Peninsula’s northern forests. Fewer than 10 employees made the shift; the rest of the new plant’s staff of 35 hailed from the Grayling area. That year also marked a change in Fred’s personal life when he married Henrietta Thomas, whom he’d met by chance at his Blaney deer camp the previous fall.

As the ‘40s came to a close, Bear Archery would struggle to prosper in its new home. Then Fred would succeed in laminating maple and fiberglass to give bow limbs the power and recovery long sought by bowyers. Arrows from Bear bows would bring down the world’s toughest game.

But those are stories for another time.

For more details on Bear’s life, read Fred Bear’s biography by Charles Kroll, published in 1988. Photos courtesy of the Pope and Young Club and The Archery Hall of Fame.

In 1972 at age 20, I purchased a 55lb Bear Grizzly bow. I practiced for several weeks and headed to Pennsylvania for their archery season ,from Ohio. After missing several deer, I managed to take a spike buck with Bear’s equipment and broadheads. Reading Fred’s books and using his archery equipment has lead to myself, my sons and my grandson all being successful archery deer hunters. I was the first family member to ever hunt this way, and the experiences in the fall woods are truly a part of my entire family’s love of the great outdoors.