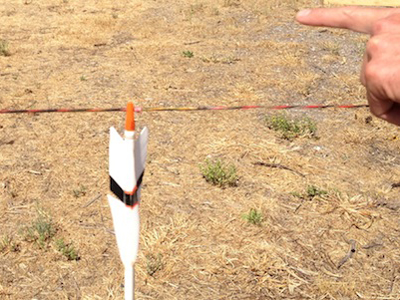

If you ever have a chance to see one of the great collections of vintage broadheads that travel around the country, do it. One might think that putting a point on an arrow shaft to make it more lethal to deer and other game animals might be a simple matter, but the amount of imagination invested in that effort over the years has been staggering. Results vary from the simple to the complex to the frankly ridiculous. We can’t possibly cover them all, but few topics arouse more discussion around bowhunters’ campfires than the choice of broadheads. In this column, we’ll examine just one element of that choice: the number of blades on the broadhead. To keep it simple we’ll stick to non-replaceable heads, since those are what most of us use.

Experienced bowhunters will be unlikely to change their minds as a result of anything written here, since many successful seasons with one style usually lead to fixed opinions. Novices confused about these choices may benefit more, and we hope that even the old-timers in the crowd will have fun with the discussion.

Two-Blade

Over the years I’ve shot them all, from old Bear Razorheads to Snuffers to Zwickey Eskimos with bleeder blades. And guess what? Give one sharp edges and put it in the right place, and any of them will kill anything from turkeys to moose.

That said, it has been years since I’ve hunted big game with anything other than two-blade broadheads (and yes, I’ve had plenty of pleasantly heated discussions with friends and hunting partners who prefer one of the options discussed below). My own track record is part of the reason. When you’ve used anything for decades with good results, you naturally tend to stick with it. However, that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Had I hunted with another style of head and enjoyed the same success, I’d stick with it, too.

Tradition is another consideration. Hunters have used two-blade heads for thousands of years. While three-blade bodkin-style heads proved effective in warfare long ago, their use for hunting purposes was a relatively recent development in the modern bowhunting revival.

But the underlying basis for my choice is a matter of simple physics. No broadhead can cut what it hasn’t penetrated, and all other factors being equal the broadhead that creates the least drag as it passes through tissue will penetrate the farthest. Of course, elements of broadhead design other than the number of blades can influence the profile of the head and the amount of drag it generates, but that just brings us back to the key modifier “all other factors being equal.” Sometimes, they aren’t.

Some fans of three- and four-blade heads claim the produce better blood trails. I can neither prove nor disprove this theory, but so many factors go into the creation of a blood trail that it’s hard for me to imagine that the number of blades on the broadhead consistently makes a difference. Besides, I consider blood trails over-rated. If you’ve killed the animal, you ought to be able to find it.

As always, the choice of broadhead design is ultimately personal, and I won’t criticize hunters who choose differently than I do (unless it’s a replaceable blade head, but that’s another story). Two-blade broadheads have withstood the test of time, and I’ve never seen a reason to change.

Don Thomas

Three-Blade

Three blade broadheads are not a new invention. They’ve been around for centuries. Museum displays show us that they came into being sometime during the Bronze Age for use as armor piercing war heads. Modern bowhunters have used them since the mid-1940s when the Whiffen Archery Company introduced their first Bod-Kin 3-blade head. Since then there have been many designs, makes, models, and variations of 3-blade broadheads marketed. Some of the newer models on the market look good and are available in a wide range of sizes and weights.

I’m kind of old school. I prefer to sharpen my own broadheads. Most of my 3-blade hunting experience has been with solid, one-piece heads. I’ve never been disappointed in them, and over the years I’ve taken a lot of game with them.

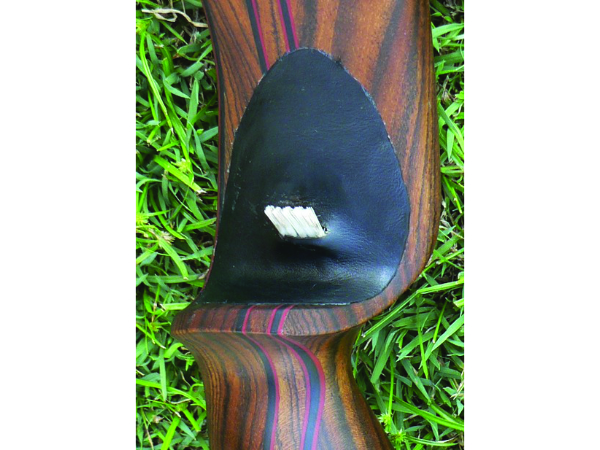

Three-blade broadheads have some advantages. They are easy to sharpen by putting two of the blades down on a flat sharpening surface and pushing the broadhead away from you. Start with a coarse stone and work down to a fine one. By turning the head and doing equal strokes with two blades at a time, you get a consistent angle on all of the blades. To finish the job, the needle tip can be chiseled just a bit to strengthen it if necessary.

I’ve witnessed some profuse blood trails when using 3-blades because they penetrate well and open up a good-sized hole that doesn’t seem to seal back closed. They often give complete penetration on big game animals. Big, old style, 3-blades leave an especially good blood trail on big game. Also, I really like them for turkey hunting. Turkeys are big, tough birds that can run or fly away after the shot unless some big bones are broken. A solid hit with a full-sized 3-blade will usually break a turkey down. Using a big broadhead will usually keep the arrow in the bird, which also impedes its escape.

I’ve witnessed some profuse blood trails when using 3-blades because they penetrate well and open up a good-sized hole that doesn’t seem to seal back closed. They often give complete penetration on big game animals. Big, old style, 3-blades leave an especially good blood trail on big game. Also, I really like them for turkey hunting. Turkeys are big, tough birds that can run or fly away after the shot unless some big bones are broken. A solid hit with a full-sized 3-blade will usually break a turkey down. Using a big broadhead will usually keep the arrow in the bird, which also impedes its escape.

The most important advantage I’ve found with 3-blade broadheads is that they don’t wind-plane in flight. I know you’re not supposed to bare shaft tune with broadheads (so don’t tell anyone about this), but I once shot several different broadheads into a large foam target using a well-tuned bare shaft arrow. I experimented with 2-, 3-, and 4-blade heads. Many of them wind-planed off the mark, and some did quite an impressive loop-the-loop, but the 3-blade flew to the mark perfectly time after time even with no fletching on the arrow. That kind of accuracy does wonders for my confidence when out hunting. Of course, with the addition of fletching they all flew well. It’s still a confidence booster though, just to know that my arrow won’t wind-plane.

Three-blade broadheads may not be perfect, but I suppose no broadhead is perfect for every application. By sharpening two blades at a time, I personally have a hard time getting them “shaving” sharp. However, Gene Wensel once showed me how to do it and he got his Woodsman incredibly sharp. So, maybe it’s just me.

Some people claim that cutouts in the blades will cause a 3-blade broadhead to whistle in flight. I can’t hear them whistle but, according to my wife, my hearing isn’t that good anyway. I wonder if the choice of arrow fletching may have more to do with the sound than the choice of broadhead.

I laugh when I remember when someone years ago asked Roger Rothhaar about the possibility of deer hearing his big 3-blade Snuffer broadhead whistling in flight. Roger just shrugged his shoulders. Then he grinned and said, “That’s the last thing they hear!”

Darryl Quidort

Four-Blade

I prefer a strong, simple two-blade broadhead for almost all of my bowhunting. Penetration is very important to successful bowhunting, and in my experience a two-blade head provides excellent penetration on large game, such as moose, elk, and caribou, and tough game such as wild hogs and most African plains game. However, there are times I prefer to use a multi-blade broadhead.

Several decades ago, when using Easton XX75 shafts, I tried out many of the four-blade heads being promoted in all the bowhunting magazines: Satellite, Savora, Rocky Mountain Razor, et al. Although they seemed like good heads, my experiences left me wanting something better. The major issue I found was that aluminum ferrules tend to bend and break when striking bone or when the inevitable miss occurs. The other issue was the thin razor blades would either break on impact or come out when the ferrule bent. Sharpening the thin razor blades is not easy; it is expected that you replace them after a shot. I like things that are reusable, and in my opinion, these were all throw-away items.

I always loved Bear Razorheads, but most of the time the bleeders either broke or came out when I shot game. The task of trying to find the bleeder in an animal before it found me—nothing worse than slicing your finger while probing a deer wound—was not something I wanted to continue doing, so I switched to a solid, two-blade head.

That being said, there are times when I prefer a four-blade head, or, shall I say, a two-blade head with a bleeder. Certain animals tend not to leave good blood trails. Bears, in my experience, are able to put a lot of distance between the shot and a blood trail due to the thick fur they sport. Hogs and javelina can also leave scant blood trails, so extra cutting edges can increase my odds of finding the trail sooner.

My favorite four-blade head is the Zwickey Delta, which has both a wide cutting design, and rigid bleeders punched out of the steel ferrule. I have shot myriad game animals with this head and have never had a bleeder break. Although not as wide as other styles of bleeder blades, it is stronger, being part of the ferrule, and creates a channel for more blood spoor.

My hunting quiver today always contains one four-blade head when hunting elk and deer, as I often run into bears while in the woods. I also prefer this head when shooting at blue grouse while hunting, as most all small game heads have proven less effective in securing these birds, the largest species of forest grouse.

T. J. Conrads

Thanks