I was slipping out from the drawn-out awards program at the Pope and Young Club’s banquet in Phoenix two years ago when a good friend, Pete McKeen of K&P Outfitting, asked me to stop by his booth.

“Hey, I have a slot open at Skinny Lake in 2016 if you want to come and hunt moose again,” he said. “Your buddy Corky Richardson bought one of the two slots at the auction today for the second hunt next fall, and I want you to come along. I’ll make you a special deal, as, well…you know, we have a long history of friendship and bowhunting, and I did build the logs for your home. I want you to come; this may be my last hunt if the owner jacks up my lease fees.”

I thought about it for a minute. It was a great place to hunt, and I have always enjoyed being in camp with him. “Sure,” I replied. “Why not?”

I first met Pete back in 2000 at the Salt Lake City, Utah P&Y Convention. He was guiding for Cassiar Stone Outfitters for moose, and both Larry Fischer and I booked a hunt for the following year with Pete. Although the events of 9/11 made air travel rather formidable, we managed to get there through a lot of politics, change of flights, and some backcountry finagling by mid-September, 2001. (See “Northern Exposure” TBM Dec/Jan 2003).

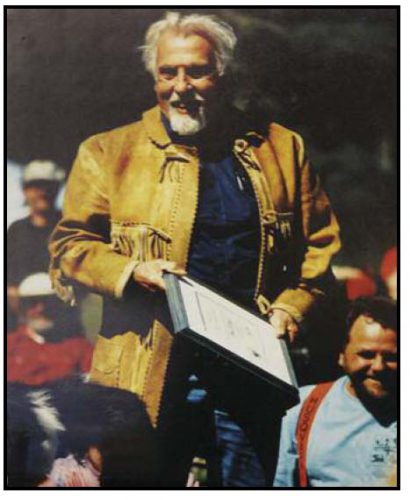

Glenn St. Charles with his smoke-tanned moose hide coat.

My main goal for that trip was to take a decent bull and have a coat made from the tanned moose hide. My late friend Glenn St. Charles had gone on a moose hunt to British Columbia many years earlier with Fred Bear. They had been successful in taking moose, and then had custom smoke-tanned coats made from the hides. I always admired that coat of Glenn’s, as he wore it at many functions we both attended over the years. I was talking to him about the hunt and that coat at a Compton Traditional Bowhunters’ Rendezvous a few years back and he related the fact that, “They stunk to high heaven! The smoke was so bad Margie made me hang it outside for months until it lost much of the smell. It never really lost it, though. Fred wasn’t so lucky; he had his coat hanging for many months and Henrietta had enough of the odor and tossed it out!”

Our hunt went well, and I ended up with a bruiser of a bull. Pete and I both agreed it needed to be shoulder mounted; however, doing so meant there was little hide left for a vest, much less for a coat. I had always planned on returning to B.C. to hunt Canada moose again, and now I had made the decision to go back and try and get a full hide for that coat.

There are myriad reasons that hunting in the far north excites the wandering spirit in bowhunters like me. Besides being able to bowhunt vast, roadless tracts of land not disturbed by man, you also have the opportunity to hunt many species of animals not native to the lower 48…and the fishing is fabulous as well. Add the fact that in almost all cases you must fly in using a bush plane, skimming over miles and miles of raw wilderness, and you have the makings of a memorable trip, dead animals or not.

Logistics are always something to think about when heading north to bowhunt. I flew into Whitehorse, YT, and chartered a ride a few hours away to Atlin, B.C. After settling into my hotel room for the night, I walked around the town taking photos and trying to find something to eat. Not much was open; however, I found, of all things, a food truck serving burgers and fries down a lonely side street. Corky and his son, Russ, arrived later that night. We talked well into the night about our flight to camp the next day.

The view of Skinny Lake from camp. From this location, you can glass a lot of real estate.

(Photo by Russ Richardson)

Early the next morning we hopped aboard a Beaver and Chris, the pilot, flew us the 80+ miles to Skinny Lake. Several moose were wandering around Atlin as we flew out, but I never saw another one until we were coming in to land on Skinny. Right before we slid onto the lake we passed over two moose: a decent bull and a smaller one.

Motoring to the small dock Pete had built out into the lake, I saw two old friends waiting to take our plane back to Atlin. Mike Parsons and Tim Fisk had hunted the ten days before us. After the handshakes and bear hugs, they relayed that the moose were scarce. They had seen very few and just a day earlier, a small bull walked by camp and Tim made a good shot. Things looked bleak, but I still had hopes of finding a bull over the next ten days. Always the optimist, I just felt things would change in our favor.

Moose are the largest of all living deer, all of which fall under the order of Artiodactyla. They are usually solitary animals during the spring and summer. Come fall—with the rut—bulls will compete for one female at a time, but also mate with several cows during the short few weeks females come into estrus. Of the four subspecies native to North America, the largest population is what we call Canada moose, but fall under the more appropriate name Northwestern moose, Alces alces andersoni. The estimated population of Canada moose is 350,000 to 410,000, of which around 175,000 reside in British Columbia. As the days slipped by, I had begun to question that estimate…

The camp is quite comfortable. The cookshack, front, also serves as Pete and Kelly’s sleeping quarters and has a shower. The bunkhouse out back has room for four hunters, a wood stove, and two tables for gear storage.

After stowing our gear in the bunkhouse, Corky and Russ went fishing while I spent time with Pete and Kelly, his girlfriend and co-owner, talking about the hunting conditions.

“It’s been slow this year,” he said. “Tim got a moose, and another hunter I have over at Disella Lake got one. They don’t seem to want to rut, but we also have a lot of grizzly bear and wolf hanging around. The moose are here, but they aren’t talking or coming in to calls.”

The boys came back with seven fat rainbows, which we promptly fried up for dinner along with a Greek salad, squash, and a succulent desert Kelly had whipped up. After dinner, Corky, Russ, and Pete went over to the end of the lake where we saw the two bulls when we flew in. Pete was able to call in a bull, but Corky said he wanted something bigger…something he would come to regret before the trip ended.

The next day we motored down Skinny Lake and hiked back into another lake where bulls had been known to visit. The day was long, as we hunted, sat, and glassed for hours from several observations areas. Pete’s soft cow moans failed to elicit a response, and moose sign was almost nonexistent. As is usually the case, the weather was all over the map: sun, rain, hail, snow, wind, and then sun again. This would be the day-to-day weather for the entire trip.

Wild blueberries are always a special treat when hunting the Far North, and they were everywhere.

The following day was much the same. We took the skiff down to the south end of the lake and hiked about three miles up a creek to another lake where we spent much of the day calling and glassing. Early in the afternoon, we hiked up to a high peak where we could see several lakes, open areas, and great swaths of swamp, willow, and grass…perfect moose habitat. The view was beautiful and the wind cold. After a lunch break aided by several handfuls of wild blueberries, I nodded off for a spell, only waking up to see the others asleep as well. It was another long day with nothing spotted or heard, so we slowly hiked back to the boat and eased our way to camp.

The nights were cold, but the wood stove in the bunkhouse would heat the place up fast; however, with no insulation, and burning soft fir and pine, the fire would burn out and it would drop to near freezing during the night. That night, we ran out of wood and around two o’clock in the morning I slipped out to grab more logs. The night was cold and clear, and when I looked up the sky was awash with waving bands of color shimmering and whipping across the starry sky. I miss not seeing the aurora borealis back home, so I just stood there for several minutes soaking in the show until the cold drove me back into the bunkhouse to get the fire going.

It was the third day and we had not seen a single moose, bear, or wolf since the first evening. A skiff of snow had fallen overnight, and the wind had kicked up. We took the skiff across the lake from camp where the meat poles were and put together a plan to hunt up and around a small hill, eventually bringing us back to the shallow end of the lake where I had seen the two bulls when flying in.

There were some fresh tracks in the thin layer of snow, and more spoor than we had seen anywhere else, but nothing was moving or responding to Pete’s cow calls. The sky cleared and the sun was shining bright when we exited the deep evergreens into the willows around the lake. I looked north and immediately saw a small bull making his way toward the shallow end of the lake.

“Moose,” I whispered. “It’s a bull.”

Russ turned and said, “It’s a cow!”

I put my binoculars on it and could clearly see antlers. “It’s a young bull, and a legal one at that,” I replied.

This was Corky’s third trip north hunting moose in B.C. I had already taken an adult Canada moose many years before, and this was an opportunity for him to try a stalk. “Corky,” I said, “I already have this species. I’m only looking for a 44-L. Why don’t you go after him.”

“A what?” he asked, his eyebrows arched and a quizzical look on his face.

“A 44-L. That’s my coat size. I already have a 200-inch Canada moose. I’m looking for a legal bull for the meat, and the hide, which I plan on having made into a moose-hide coat,” I replied. “You, on the other hand, are on your third hunt for moose. Go ahead…”

He looked at me, then at the bull for several seconds, turned back to me and said, “Naw, I will wait for another one. I want to watch you shoot it!”

I looked at Pete. He grinned and said, “Want to try? What have we got to lose?”

“Hell yes!” I replied. “I may not shoot him, but if we get close, and the shot presents itself…I’ll seal the deal.” Why not, I thought; I had a new bow, good friends with me, and a chance to cleanly take an animal—it was worth the opportunity. I was rather giddy; I had nothing to prove to myself waiting for a bigger bull; I was more interested in a clean kill, meat, and the coveted hide to take home.

Corky and I out fishing for fat rainbows. The hunting may have been slow, but the fish entertained us for hours.

(Photo by Russ Richardson)

The bull slowly made his way to the lake where he stepped in and started drinking and eating grass. Pete gave several cow calls and although the bull looked our way, he paid us no interest. It was time for Plan B, whatever that was.

Corky had brought a Predator cow elk decoy with him that is manufactured by a friend of ours. Designed to be strapped onto a bow, it was very light and compact…and very convincing with its 3-D photo image of an elk. It looked nothing like a cow moose, but it did have long ears, so Pete and I went into action. Pete looked over the decoy, then at me and said, “We might as well try, right? He’s not coming to us!”

Two spruce trees separated us from the bull, as well as several small clumps of willow along the shoreline. We needed to close the distance, so Pete put the decoy in front of him, I pulled up behind him, and we slowly duck walked toward the spruce trees. Every time the bull put his head down, we would grab a few more steps. When we got to the trees, I realized the setup was not going to work as planned; I needed to be closer to the water.

The bull had finally given in to his curiosity and decided to mosey his way down along the bank toward us, stopping every now and then to drink and rip some tasty morsel from the water’s edge. I saw a small clump of willow about fifteen yards closer to the lake and crawled my way there. Pete had followed me with the decoy, and then retreated back to the spruce. Slowly, the bull made his way up the shoreline toward the decoy Pete was bobbing up and down.

The cover was sparse at best. I backed into the willow as far as I could, pulled my beanie down over my face, nocked an arrow, and got as low as possible to the ground. I could hear the bull’s footsteps in the shallow water as he made his way up toward me. It sounded so close as I dug my face deeper down toward the ground. I tried to settle down, taking deep breaths. It was obvious he was going to walk right by me when all of a sudden he stopped; he did not like the blob I had become as he came into view.

A perfect shot, easy recovery, and friends to help in butchering. You can’t ask for much more.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw him broadside to me. As he started to turn I heard the water move and I lifted up my torso while drawing back the shaft, picked a spot, and released in one fluid movement. There was a loud crack as the arrow entered right where I was looking. It buried to the fletching, far back on his right side angling toward the off shoulder. Blood spewed from his side as he ran across the shallows toward the other side. He made it about sixty yards before he tipped over. It was like slow motion. The entire event took less than a minute.

I was trying to process what had just happened, replaying the event in my mind’s eye, when Pete ran up, more excited than I was, and yelled, “Great shot! The arrow is perfect!” as he bear hugged me. I turned back to look at the bull, my arrow glistening in the afternoon sunlight, and gave thanks for such an exhilarating experience, and a clean kill.

I looked up the trail and saw Corky barreling toward me, a grin stretching from ear-to-ear. He grabbed me and squeezed me hard. “That was the most incredible shot I have ever seen with a bow, brother! Russ got it all on film!” It was a memorable experience, shared with good friends, but then the real work started.

Pete walked down the lake to retrieve the boat, while Corky, Russ, and I walked around the shallow inlet. When Pete came back, we had to drag the bull out to deeper water until we could float him back to the meat pole. After several ferry trips to get everyone over to where the bull was, we went to work skinning, quartering, and hanging the meat.

Fresh moose tenderloins were on the menu that night.

A complete side of moose ribs slowly roasted by an open fire.

The rest of trip I stayed in camp working on the hide with Kelly, cooking, fishing, and writing while Corky, Russ, and Pete tried to find a bull for Corky. Each night Kelly and I would have dinner prepared when the boys arrived back in camp. The meals included moose stew, tenderloin steaks, moose burritos, moose tongue sandwiches, and something I have wanted to do ever since I saw a photo of Fred Bear roasting sheep ribs by an open fire: a slowly roasted, complete side of moose ribs, which I tended to for hours. Lathered with a BBQ sauce I whipped up with tomato sauce, vinegar, brown sugar, and several spices at hand, they were delicious, and we ate the entire side at one sitting. It was a dog party; everyone ate like dogs. It was a fantastic, albeit messy, meal.

By the end of the hunt, Corky had only one other opportunity on a bull, but was caught out in the open. The bull knew something wasn’t right, and circled around until he got downwind. That was that. There was a close encounter with a grizzly, too, but that story is for another time.

Pete, the author, and Corky getting ready to dig into moose ribs.

(Photo by Russ Richardson)

Not all hunts end with game on the pole; however, even one moose can supply several people with meat. As we waited for our bush plane to pick us up, I decided to share my good fortune. As a gesture of thanks for all the help everyone had been, and since I already had a deer and elk in the freezer back home, I gave Corky and Russ a front quarter each, Pete and Kelly one of the rear quarters, and I took a rear quarter and backstraps…not to mention enough hide for my 44-L.

T.J. Conrads has an affinity for the Far North, and for creating culinary dishes with wild game he has taken…moose ribs cooked by an open fire is one of his latest.

Equipment Notes: T.J. used a 56# Black Widow takedown longbow, homemade tapered cedar shaft with a 75-grain Woodyweight, and Cliff Zwickey broadhead to take this moose.

Leave A Comment