There has been a controversy in bowhunting history circles since 1989 when Bill Negley published Archer in Africa. Two questions were central to Negley’s claims in the book, and there was a chapter dedicated to each: Would it Really be the First? What about Howard Hill? and What about Bob Swinehart? respectively. Who was the first to successfully bowhunt the African elephant under fair chase, and who was the first to successfully collect all of Africa’s Big Five? Negley contends he was the first to do both, though convention until that time was that Bob Swinehart was the first to take the Big Five, and Hill the first at the elephant. The stories and historical record are muddied, vague, and complicated by rumor, jealousy, elapsed time, and the perspectives of the day. Howard Hill was missing the rhinoceros in the chase for the Big Five, but nonetheless Howard is embroiled and central in this controversy because of the enormous African elephant that he killed.

Hill’s mission in Africa was quite clear. He was financed to, first and foremost, film a profitable and entertaining major Hollywood motion picture called Tembo. Secondarily, he wanted to kill some of Africa’s big game with his longbow to prove the effectiveness of the bow and arrow, as well as prove to himself he was capable of those accomplishments. The problem was that movie-making technology of the early 1950s made it very difficult to capture with any clarity these bowhunting action sequences on film. The lighting was critical, the equipment heavy and cumbersome, and a film crew of several people were necessary to accompany him on a stalk and shot sequence. This was a very difficult, if not impossible, task when trying to get all the action on film with dangerous game at bowhunting distances. Imagine stalking up on a lion or cantankerous rhino with three camera guys outfitted with tall whirling camera gear, a professional hunter with backup rifle, and a couple trackers.

Hill therefore may have done what he needed to do to get animals on film, and this is where later critics like Bill Negley take exception. It was suggested to Negley by Bob Carpenter, that Hill had his professional hunter knee-cap the elephant to get the close-in bow shooting and action shots on film. This was supposedly proclaimed to Mr. Carpenter by some of Hill’s camera crew and assistant hunter when he was camped a few miles away from Hill’s camp during the filming. The story was that the group traveled daily to Carpenter’s camp after sundown for some cocktails because Hill was a teetotaler (not a drinker) and had a dry camp. Hill’s own written words and collaborating stories since prove that this basic premise was not the case. Mr. Hill enjoyed his drink as much as anyone, and even overindulged at times in his life.

In any event, it was clear that the Tembo elephant was in question as a fair chase kill, and other animals such as the lion and leopard in the film Tembo can clearly be seen to be “restrained” or snared to get the requisite action shots for the feature film. Leopards are nocturnal, and this was likely the only way to get a leopard shot on film in daylight in those days. Unfortunately, these methods to get action shots on film for show business are extrapolated to all of Hill’s game in Africa. What is left out of his detractor’s accounts though, is the fact that Mr. Hill spent many months in Africa, and shot several other animals off camera. He shot two other elephants with the bow, not on film, and he would have had no reason to take liberties with rifle or snare. There has never been any film footage of the other two elephants, and it should be assumed they were not “handicapped” before being arrowed. Remember, Hill was also interested in proving the effectiveness of the bow. In Wild Adventure Hill recounts his unsuccessful shot at a bull elephant. A small branch deflected the arrow and it ended up striking the jaw, embedding in a tooth. The pachyderm ran a few hundred yards, shook off the initial shock of surprise and removed the arrow. Then it ran back to search vengefully for the source of his discomfort. “For a full two minutes, the maddened elephant ran first in one direction, then in the other, trying to locate us. We could have killed him half a dozen times with the heavy rifles, but knowing that he had received a very slight wound from the arrow, we did not want to shoot him with the rifles unless forced to do so in order to save our own hides.” This elephant was clearly not knee-capped before being shot with the arrow.

Hill was never able to get a rhinoceros with his bow. When it came time to hunt the rhino, he had broken his bow hand and was not able to pull his heavy bow. He did not want to risk a shot with a lower weight bow on such a giant animal. Therefore, Hill was not in contention, nor ever claimed to have achieved completion of the Big-Five.

Negley traveled to Africa in 1957 and did kill an elephant with his bow, but it was not until after Hill’s death that he contended that he was the first to successfully do so under fair chase. It seems he carefully avoided speaking to Mr. Hill, or challenging the validity of being the first, until after Hill’s death.

Nine years later, in 1966, Bill Negley heard that Bob Swinehart had announced that he was on a mission to kill the Big-Five with his longbow and was getting a lot of good press. Bill was envious no one was talking about his accomplishments, and he decided to come out of dormancy with the bow and arrow and try to beat Swinehart to the punch. After all, he had already collected the elephant in 1957. The race was on!

Unknown to Negley, Swinehart managed to complete the Big-Five by killing a lion prior to Negley even leaving for his safari in 1966. When Negley returned from the bush after completing what he thought was the winning kill, he learned of Swinehart’s success and conceded publicly that Bob was first.

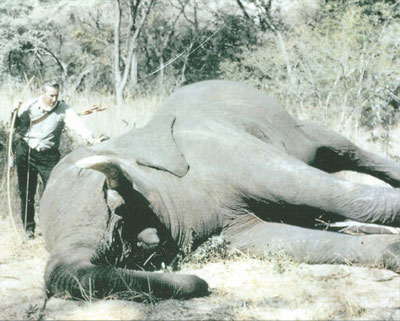

Swinehart’s second Angola elephant.

After Bob’s death in 1989, Negley was meeting with a group while planning another African safari, when one of the men at the meeting, who was an assistant professional hunter in camp on Swinehart’s elephant hunt but not actually witness to the events, told Bill of the gossip around the camp. The word was that Swinehart also first anchored the elephant in the knee with a rifle before shooting it with the bow. Negley contended that is how Bob was able to get so close, get three arrows in the bull, and get some of the pictures of the event published in Sagittarius and In Africa. Negley then published his book Archer in Africa, claiming that he was the first to kill the Big-Five under fair chase, and that he accomplished it largely without rifle backup. All of this was based on second hand hearsay, in contrast to what Bob wrote in his publications, and without Swinehart being able to defend himself from the claims. In addition, Bill fails to recognize that Swinehart also bow-killed a second elephant in Angola. Swinehart recounted that he wanted to prove that one arrow alone could be responsible for the demise of such an enormous beast. This he accomplished on this second bull.

Bob went out of his way to explain that his first rhinoceros was not a valid bow kill because it charged after his arrow struck a fatal shot, and had to be put down by rifle fire. He was published as stating, “Any bullet striking the animal would have destroyed my chance for a bow kill.” He had to travel back to Africa on a subsequent safari to get his rhino. This does not sound like someone who would take liberties with knee-capping an elephant to me.

Despite all these tales and controversies, each man; Hill, Negley, and Swinehart have their place in The Bowhunting Hall of Fame. Hill’s legacy is well documented with a list of accomplishments that will never be rivaled. Negley went on to bowhunt many species and examples of Africa’s dangerous big game largely without rifle backup. Swinehart, whose life was tragically cut short, still managed to follow in his mentor’s footsteps by igniting bowhunting dreams through shooting exhibitions, presenting talks and slideshows at events, and publishing two cherished bowhunting books that are still regarded as must-read classics for those that can acquire them. Each has earned their place in history, interconnected by the mighty African elephant.

This is an old controversy that should be viewed primarily as a matter of historical interest. We addressed it from one perspective recently in the print magazine (Dec./Jan. TBM), but wanted an opportunity to present other viewpoints as Greg Ragan has done. I admit some bias in that I knew Bill Negley personally, but have always emphasized that I only know what he told me, and he was always up front about the fact that he only knew what other people told him.

Hill was clearly a far superior archer, but I think Bill deserves some special credit for declining rifle backup. At this point it’s best if we all admit we’ll never know the truth of the matter. And what difference does it make at the end of the day? Hill, Swinehart, and Negley were all three accomplished, pioneering bowhunters. It really doesn’t matter who did what first.

Don Thomas

Dear Dr. Thomas, you may remember me as the guy who sent you pictures of what I perceived as a possible granddaddy of the take down bow. A shoot through metal riser in which the sight pins were housed. My near 70 year love of doing it our way began as a lad of about 14, when my buddies dad came from the house with a bow and handful of arrows. That day changed my life in so many ways. His name was Earl Wambold and he, his wife and two sons were big into archery. How big I had no idea at the time. I was a tyro. From his back yard began a trip through life that has never lost its affect. Through him, I was fortunate to meet and shoot with some of the big guys. As a lad of 13/14 to meet Sasha Siemel,who either belonged to or often frequented our club, was the a thill like no other. Earls youngest son now resides near Norristown , Pa.. In a phone conversation a few years ago, Terry, the last of his family, informed me thst he and his dad had made many visits to Sasha and Ediths home. He lived jn the small town of Sumneytown, not far from where I grew up. I never had the chance to join them. One evening he came into the Inn, where we held our meetings, bringing films of his hunting jaguars with spear and bow. He handed me a spear and to hold that weapon in my hands elicited a charge that is still locked inside me. When rotating the spear in my hands, I noticed a few deep impressions near the blade end. Sasha implied that he was glad those were not in his arns. On my wall hangs an arrow he gave me he had found while shooting the course when Earl and I were walking up to the practice butts. as he was walking down. Our club was the Perkiomen Valley Bowmen in a conference, which also included the clubs Unami in Emaus, and Popodicken in Boyertown. That same year Earl took me to a tournament at Unami, the club Bob Swinehart started up. I stood by as Earl was greeted by several who were present. One foursome was short a bowman. They invited me to join them. I remember one shooter was left handed and gave me many tips as we went through the course. He was a Bob also although I had no idea of who he was. On the way home Earl told me who he was which did not register until much later due to what I believe, in retrospect, he had not yet accomplished. This would have been in ’53/’54. But I’m 90% sure it was him who was so polite and helpful. I’m lucky to have his book Sagittarius (1st. Ed.) and Sashas book, Tigrero in my collection. The last big timer I had the chance to shake hands with, was at the bowmens festival in Forksville, Pa. while a member of the Great Swamp Bowmen near Quakertown, Pa. Thinking it was ’61. We learned that Howard Hill was a few targets behind us so, when we finished the course, we hung around to wait to see him. I was excited to shake a hand that had seen so much action regarding our way of life. My last club was with the Endless Mountain Archers in Susquehanna County in NE, Pa. having moved there in ’62. After many tournaments, I finally had to slow down. I’m only 82 now and still trying to keep on keeping on. But as we all know, time out lasts joints. The bows are lighter now but still bend. My thanks to you for sharing with us your adventures in the world of archery done our way. I only ever dowbed one deer and that was in ’64 with a borrowed .32 Winchester, the year I went into the Army. But I was hell on pheasants and small game with my bow. I decided I did not like deer meat so I never shot another deer. Earl taught me, with the exception of varments, to never kill what you won’t eat. But he never did tell me to not go into the woods to find out who you really were and where honesty prevailed. You too have kept me in the game by way of your vast experiences in the only way to hunt. My heart felt thanks to all at TBM for the best mag out there. . Bob Way, Factoryvile, Wyoming county, Pa.