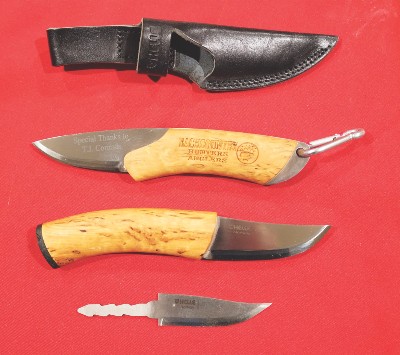

A full tang blade Helle knife top, and partial tang below. Helle sells complete knives as well as tangs and parts to make your own.

I remember my first knife. My father gave it to me when I was quite young. It was made by Schrade with two folding blades made of carbon steel. Along with the knife, I also received a stern lesson on how to use it and, more to the point, how not to. Those lessons remain quite vivid in my mind to this day.

Dad was a sportsman of sorts, traveling every year from our home in southern California to Colorado to hunt mule deer. He was quite good at gun hunting, averaging three mule deer a year, a couple of blacktails from northern California and southern Oregon, and a bear once in a while. What he was terrible at was cooking game and fishing, but those are stories for another time.

Speaking of Schrade, I still own several and use them all the time. They are inexpensive, easy to sharpen and keep sharp, and have stood the test of time in both full tang and folding knives. I have also lost a few of my favorites and found several as well while in the woods or along a good trout stream. Over the years I have found four or five Schrade Sharp Fingers—sold under the trade name Old Timer—while hunting, but never in a sheath. The sheath Schrade made for this model never held the knife securely. I still have two that I found, one while bowhunting with Jerry Gowins back in 1992 in an Oregon forest while chasing blacktail deer, the other out in the vast Idaho desert while crawling around stalking antelope. I have lost several good knives from bad sheaths as well. Make sure that the knife you do buy has a high-quality sheath that holds the knife securely, which many do not.

I have always carried a knife. For many years it was a pocketknife, then a Buck 110 folder, which was sheathed on my belt for many years and still sits in the door pocket of my hunting rig. Today, though, I prefer a folder that clips onto my front pocket where it is available at a moment’s notice. This is my everyday carry knife, and I always have one except when flying—a lesson I learned the hard way. I have no idea how many of my pocketknives are hidden under sinks in airport bathrooms after forgetting to pack them in my checked luggage, but it is more than half a dozen. One of them is hidden at Charles De Gaul airport in Paris, which I plan on retrieving as soon as I can go back once this virus issue settles out. I managed to retrieve two over the years, but now I am not sure which airports the others are at!

There are literally thousands of brands of knives the world over, from mass produced to a booming custom knife industry. It seems that every time I turn around there is another custom knife maker in business, and I own several dozen custom knives that I have picked up over the years from speaking engagements, gifts, silent auctions, and personal investments. Many of them have never been used, but still hold a special place in my heart. But one thing for certain is that what I like in a knife may or may not be what you like, which may be why there are new custom knifemakers coming out of the proverbial wood pile every year.

For my general hunting, I like a full tang, drop point knife as my go-to blade. My current one is made by knifemaker Mike Okamura—a drop point with spalted maple and antler handles. I had Mike make the leather sheath so that it rides horizontally on my belt line in front for quick and easy access, as opposed to riding vertically on my side. I also carry another custom knife by well-known bowhunter and knifemaker Wayne Depperschmitt from Colorado. It, too, is a full tang knife, but has a sharp point and thick blade for piercing skin and separating joints in big game. In addition, I always have a quality steel in my hunting pack to keep the edge sharp.

I am not a huge fan of stainless steel knives. Most stainless is very hard, which makes putting on a good edge time consuming. Applying a steel often when working with one will keep the edge sharp, but once it gets dull it may need to be put to a stone again. Some of the hardest steel I have found is used by Case and Buck. My father showed me how to sharpen such knives, and I can still see him sharpening my mother’s kitchen cutlery and using his Case knife as a steel, as it was much harder than the actual steel we had in the knife block. I own a complete set of Case kitchen cutlery that my father gave to my mother back in the 1960s.

High carbon steel makes for a knife that is easy to keep sharp with a steel. Many years ago while bowhunting in the Northwest Territories, the guides used 10” to 12” high carbon Old Hickory knives. Skinning and boning caribou all day takes a toll on knives, but a few strokes on the steel and they were brought back to shaving sharpness in no time. My favorite kitchen knives are all high carbon Japanese Shirogami White #1 steel knives, which I consider superior to any other knife I own. I am still on the hunt to find a source of hunting knives of such quality, like the Fred Bear in the leaterh sheaf in the photo on page 61 with stone and file.

High carbon steel is made by adding carbon to steel made from iron ore. It rusts and stains easily; however, the edge it holds is superior to any other knife I own. Stainless steel is created much the same way, however chrome is added, which prevents the steel from rusting. This is why almost all kitchen cutlery today is made of stainless steel, as are most hunting knives.

The latest craze I see is the single bevel knife. I have several Japanese kitchen knives with a single bevel edge. I don’t care for single bevel knives, as the bevel side creates pressure (read friction and resistance) that forces the knife to move toward the flat edge while cutting, which makes for uneven thicknesses. I have resorted to grinding them into double bevel edges of, which allow easier, and exacting, cutting of meat and vegetables in a more uniform thickness, as the blade travels straight rather than angling toward the flat edge to create uneven slices. However, I do have a few high quality French Sabatier 4-star Elephant and Japanese high carbon knives that have a slight back grind to the single bevel blades that work extremely well due to the blades being much thinner than my other Japanese kitchen cutlery.

One last mention is a caping knife. Many years ago we had CRKT make us a two-knife set that came in a single leather sheath. They were skeleton knives, very light weight. One was a general purpose knife that was designed to gut, skin, and break down big game. The other was a smaller caping knife. They weighed next to nothing, and were big hits; however, CRKT discontinued them, so we were unable to restock them. Today, though, several manufacturers make scalpel-like caping knives with replaceable blades. They work great, but from my experience they dull rather fast when working on big game such as elk. The other negative is that many hunters simply toss the old blades onto the ground instead of hauling them out of the woods. I have a handful that I have found in my elk hunting area, as well as beer cans and other trash that I end up putting in my hunting pack to dispose of properly.

The knife may be one of man’s greatest achievements in tools. We know that paleo man used many primitive tools as a knife, and Native Americans learned to make excellent blades from chert, obsidian, and other natural materials. Today, the knife is a necessary and utile tool that is, perhaps, the most widely used tool in the world.

There are literally thousands of types of knives, both custom and mass produced, available to the outdoorsman. Finding the ones that fit your needs may seem daunting, but the journey is part of the mystique of the history and lore of the ubiquitous knife.

T.J. Conrads

A sample of neck knives from Asbell Wool.

How many knives do you own? If you are like me, you own more knives than bows. Knives are definitely a part of my life and have been as far back as I can remember. As a kid I was completely wrapped up in cowboys and Indians, and with my Dad’s always razor-sharp Case pocket knife I made play knives, tomahawks, and guns out of every piece of wood I could lay my hands on. As soon as I was old enough, and every day since, there has been a pocket knife in my right hip pocket.

Knives haven’t changed a whole lot over the last century. Different and better steels have come along, but basically they haven’t changed like most other things in the outdoor world, and that probably means they’ve been doing the job they were intended to do right from the start. I consider a knife one of man’s best inventions, and there’s rarely a day that I don’t pull mine out and use it for something.

As a bowhunter, the right knife ranks up there with choosing the right broadhead, and like broadheads you’ll probably go through several before you decide which one works best for your needs. I’m mostly concerned with processing animals. I have distinct opinions, most of them formed through usage. I’m not big on specialty knives like thin skinning blades with rounded points, saw teeth, gut hooks, spring blades for instant deployment, etc. They are like specialty broadheads. Most of them are intended to address a problem someone once had, and this is their idea of a solution.

The blade shape is the first thing I look at. I like a straight, sharp point with maybe a little drop, or a longer spey blade, and I want the knife in general to fit my hand and be simple and convenient once I’m inside an animal. Big knives are impressive and are fine for some things, but there’s not a lot of room in there and big wide blades are usually clumsy and unwieldy, getting hung up too easily. Of course, with the larger animals—moose, caribou, big bears—something larger may be the way to go.

Folding Blade or Fixed?

Like a lot of things in this outdoor world, it’s mostly a matter of personal taste based on some level of experience. The first bowhunters I knew all carried big folding knives in a sheath on their belt hanging down in their rear pocket, and so I do now as well. Case and Schrade were popular, some with a single blade, some with two. They were inexpensive, worked well on small to medium sized animals, held a good edge, and were available in any sporting goods store. They’re still a good choice. For several years, I carried a Schrade that I bought from Herter’s.

A folder is convenient, easy to carry and can be big enough to handle most tasks you ask of it. My problem with a folding knife is the inconvenience of getting to it and bringing it into play when you need it in a hurry. A regular pocket knife carried in your pants pocket is the same problem multiplied.

Has that been a problem I’ve encountered myself? Not specifically, but I think about hanging on the side of a tree in the middle of a tree stand problem and needing to get to the knife in my pocket. Part of being a woodsman is being able to avoid or extricate yourself from those kinds of situations. If I’m in a tree stand, there’s always a sheath knife on my belt. I also carry a bigger sheath knife any time I think I might need it for personal safety or survival. Overly romantic? Perhaps. Safety conscious? Yes. And for me, therein lies the determining factor in preferring a folding knife or a fixed blade knife.

Having a knife and not being able to get to it is the same as not having a knife. I’m reminded of an early hunting buddy who always carried his custom folding knife in his pack. Mostly he used mine when we hunted together because his was expensive and it was too much trouble to get to it.

Also, there’s usually a neck-knife hanging around my neck within fingertip access when I’m in the woods. Even though they’re typically smaller, a neck knife is a good outdoor knife setup, for hunting, camping or just being out there. I’m rarely without it anytime I’m out. I think the American Indians or maybe the mountain men get credit for its existence. Necessity, they say, is the mother of invention, and the neck-knife fits right there.

I prefer carbon steel over stainless. Good carbon is tougher, sharpens easier, and holds an edge better than stainless, and I think it’s more traditional. But no matter the material or the design, your knife must be kept sharp, and that’s where stainless is less appealing to me. It’s considerably harder for the average person to sharpen a stainless blade. A dull knife is not much better than no knife. Know how to sharpen any knife you carry and have the tools at hand when you need them.

Having said all of this, there is never a moment when I don’t have a pocket knife in my right hip pocket, regardless whether I’m wearing wool hunting pants or a suit. I’ve carried a red Swiss Army knife (DEP) with a main blade, a flat-head and a Phillips head screwdriver (instead of a corkscrew) for a long time. There’s also an awl, can opener, bottle opener, toothpick, tweezers and it’s a lock-back. It’s good steel, takes a good edge, and there’s an eyelet for a deerskin thong that makes it easy to grab and pull out of your pocket. I haven’t tried to build a house with it, but it’d be good to have handy if you were in the process. When I’m bowhunting, there’s a fixed blade on my belt, a neck knife hanging around my neck, and a pocket knife right there in my right rear pocket, and I don’t feel over-equipped.

G. Fred Asbell

Recently, Don Thomas outlined four types of hunters. While I can identify with all four, the “Process Hunter” certainly describes me to a great degree. I absolutely love objects crafted from wood, leather, and steel, especially when they are made by hand.

Edged tools come in many shapes, sizes, and forms. All have their own unique characteristics that cater to certain chores more than others. With all of the different looking blades and flashy marketing, selecting the proper knife can be confusing, but it definitely warrants some thought, and perhaps some research into the proper design for its intended use.

A good representation of the types of knives that Luke discussed, starting from middle-left: TOPS Knives “Camp Creek” (Nessmuk), Greg Moffat Knives Kaniksu 8″ Skinner (trailing point), vintage Othello Skinner (trailing point), TOPS Knives OnPoint Tactical (clip point), Cold Steel Mackinac Hunter (clip point), Cold Steel Pendleton Mini Hunter (drop point), Cold Steel Pendleton Hunter (drop point). Far Left: Fiskars Normark filet (trailing point). Far Right: The Backcountry Roll from Tyto Knives, which includes a Tyto 1.1 (replaceable blade) and Fannin 3.0 fixed (straight back: not discussed). Bottom L-R: Greg Moffatt Knives GL- 1 (drop point variation), Wenger Blades EDK (drop point variation).

When you think of a “hunting” knife, likely the classic lines of Dad’s old “skinner,” Grandad’s Buck 110, or Case Stockman folders come to mind. Nowadays, while people tend to be more absorbed in their outdoor passions, we also have easy access to a wide variety of high-quality gear. There’s no shame in having more than one tool on hand for any job when it comes to thriving out in the bush and taking care of our hard-earned game.

Let’s consider blade designs. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll only look at the designs most commonly used in outdoor applications. When considering knives, there are four shapes that I’ve found to be the most useful (in no particular order): drop point, clip point, trailing point, and Nessmuk. You’ll find these designs available from essentially every knifemaker, in some variance or another. Likely the most versatile and widely used of these blade profiles would be the drop point.

The drop point is great for just about every task. It’s a simple yet versatile design that allows great flexibility in different applications. The spine tends to be extra thick, which adds strength to the blade. This is crucial when carrying out more demanding chores like chopping through smaller sections of wood for fire prep. The point is usually fine enough for detail work, yet strong enough for drilling holes or prying around the joints of an animal when breaking down the carcass. You’ll find this blade shape very common in EDC (Every Day Carry) designs, often with a 50/50 plain and serrated edge combination. Having the back half of the edge serrated is great for cutting cord and webbing or making shavings for fire starter material. My favorite example of a drop point folding knife would be the Griptilian from Benchmade. I count this as my first “real knife” purchase, made while in my early twenties in preparation for a backpacking trip. Other examples of my favorite drop point fixed blades include the Pendleton Hunter and Pendleton Mini Hunter, both made by Cold Steel. I actually have these two knives mounted side-by-side in a custom kydex sheath, made for me by Robert Humelbaugh, at Survival Sheath Systems. I should also mention the 6” Greg Moffatt GL-1 that lives on my belt horizontally as an EDC.

The clip point is another well-known and versatile profile. Likely the most recognizable knife based off of the clip point would be the Bowie knife. This profile has long been in use and has a rich history. A very long cutting surface with a belly that juts out straight and trailing upward into a tight point make for a knife capable of most cutting, slicing, and chopping tasks. A classic example of a folding clip point would be the Buck 110 mentioned earlier. Another of my favorite fixed blades of this style, is the on Point Tactical, by TOPS Knives. I have two of these knives, both with fire steel mounted to the sheaths.

The trailing point is the classic “skinner” profile, with a large amount of cutting surface due to its upswept belly. This feature helps provide a lot of slicing power in a shorter overall length. My father’s German-made Othello skinner lived on his pistol belt for as long as I can remember. Its stag horn handle and curvy lines always come to mind whenever a “hunting knife” is mentioned. This design excels when it comes to field dressing game, as well as processing meat for the freezer. Last year on a whim, I broke out my dad’s old Othello skinner, a new Greg Moffat Kaniksu skinner, and along with a few other knife designs, I proceeded to dress out the buck I had just killed. It was a great experiment, and I took note how both knives utilizing the trailing point profile excelled.

The Nessmuk is the lesser known of the above-mentioned profiles, but dates back to the 1880s and originates with conservationist and sportswriter, George Washington Sears, who’s pen name was “Nessmuk.” It’s a variation of the trailing point but has a much wider tip and a deep belly that adds weight and slicing power. This blade profile excels at bushcraft chores, food prep, and skinning, and has become one of my favorites. The larger overall size compared to that of a standard trailing point skinner may be an advantage when it comes to field dressing extra-large game like elk and moose. Awhile back, I was visiting the TOPS Knives booth at a trade show and spotted their Camp Creek model. I coughed up the $200 for the knife and haven’t looked back.

I originally scoffed at replaceable blade knives, assuming they were just part of the mass production “convenience” trend that steadily pulls away from skill and tradition. But then four years ago while on a family elk hunt, my best friend and I assumed the honor of field dressing the bull that his uncle killed. I broke out a knife that I had somehow neglected to re-sharpen after its last skinning task, and my friend unleashed his replaceable blade Havalon, which seemed more scalpel than “hunting knife.” Before long, I was noticing the effects of my dulling edge and was wondering if I had either a field sharpener, or a fresh knife nearby. Meanwhile, my friend was merrily working through his half of the task as I watched him pause to snap off a dull blade, replace it, and motor on. It was a little humbling, and it made me realize that I had been considering the matter from a narrow point of view. Since then, I have found Tyto Knives and have added one of their Backcountry Rolls to my kill kit. At least that includes a lightweight, fixed blade knife included, which assuages my guilt just a little while rounding out the kit’s capabilities. Between field dressing, caping, food prep, and camp chores, the BC Roll is a great investment that takes up very little room in your day pack.

Luke Johnson

Leave A Comment