The sea breeze was noisily rustling the palm fronds when I heard a slight splash from the freshwater slough just to my south. The water was hidden by thick palmetto ground cover. A trail ran parallel to the slough between prehistoric sand dunes covered by thick palmettos that grew head high in places. Scattered live oaks, palm trees, and a few giant slash pine rose above. Abundant live oak acorns, mostly cracked shells from feeding hogs, littered the trail under the oaks. The area was called Jungle Road on the topo map, and aptly named. If a pterodactyl had flown by I would not have been surprised. Every time I am here I think of Will and Maurice Thompson. They would have approved.

There! I heard it again, accompanied by a low grunt. Suddenly it sounded as if a herd of buffalo hit the slough and was headed my way. My heart was pounding as the hogs began crashing into the palmettos on the low ridge twenty-five yards in front of me. Then all was quiet.

I noticed my legs were shaking, but my bow arm was steady and the string loaded as I felt for the slight breeze. The wind was holding steady from the south. Nothing moved, and I was beginning to believe the hogs had turned into the ghosts they could be and had slipped off somehow after sensing my presence. Then there was a tremendous blood-curdling squeal, and a hog sailed over the top of some waist high palmettos and landed on his side with a thump in the middle of the trail. The boar quickly gained his feet and dashed back into the thicket. He was at least 125 pounds, and I was considering what tossed him like that when a sow exited the palmettos and trotted down the trail toward me followed by a lot more hogs.

The Jungle Road double.

I was seven yards off the trail, and now I only focused on the sow’s front leg knuckle. In a few seconds she covered the distance and by some miracle didn’t pick up my scent as my heavy arrow drove through low on the shoulder. The sow whirled, scattering hogs everywhere, and they all made a quick dash back to where she started. I saw the arrow location and knew she was dead on her feet.

Without conscious thought, I instantly had another arrow on the string, never having taken my eyes off the melee. Just as the sow disappeared one of the other hogs, a throwback of white and black spots, caught my eye as it hesitated behind a palmetto frond on the edge of the thicket at twenty-three paces. A few seconds after the first arrow, my second arrow was on the way, piercing a palmetto frond and pig, which disappeared toward the slough squealing. I slowly eased up to the thicket. Blood covered the palmettos, and I could see the nice sow lying just inside.

My wife Krista heard all the commotion and slipped up silently. She quickly located the second hog, a boar. I never saw what must have been the brute that hurled the boar onto the trail. They get big being cautious.

We were hog hunting and, for today anyway, hog shooting. Too often hunters only get the hog shooting part and miss the thrill of real hog hunting. If you have only shot hogs over bait from a stand, or followed a trail of corn down a sendero, you never have given a hog a chance to prove it’s worth. Few things can match the fun and challenge of ground hunting hogs with a bow in a river swamp or palmetto and live oak country.

There is a reason wild hogs are depicted on cave art in Europe and were held in esteem by royalty. They can be tough customers, and under the right situation dangerous. Too many are killed today that were in a pen a week ago and have been habituated to bait. Actually getting out and finding free ranging sounders is similar to patterning deer. In some ways it is easier, and in some ways more difficult. Finding an old, mature, solitary large boar and getting an arrow in him can be just a matter of rare luck unless several are fighting over a sow. Their roars and squeals can lead you to the battle if you don’t lose your nerve. Few sounds are more intimidating than what you hear as you ease into a thicket with a group of large boars battling for breeding rights over a ready sow.

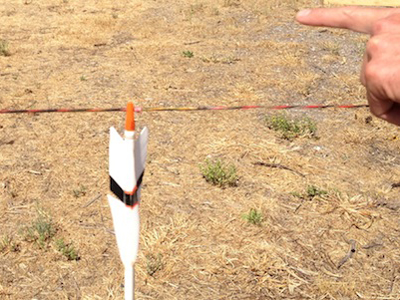

A perfect shot, low in the shoulder, with a Grizzly broadhead.

I have walked out of the swamp plenty of nights listening to low growling grunts of big boars close by, knowing I was there and displaying no fear in the dark. I have mostly hunted hogs for delicious meat, so I have tried to avoid the larger boars once I had sampled a few. All boars have a distinct, not very pleasant smell that can permeate the meat. Smaller boars under 100 pounds are milder. A big, fat sow that is barren is best but hard to find, as the females have up to three litters a year. A heavily pregnant sow or one nursing piglets makes poor eating, so pick your target carefully.

Their proliferation and rapid spread in the last twenty-five years after 500 years in North America has caused a mindless panic among wildlife managers, and on the federal level, millions of dollars have been spent on hopeless attempts at eradication. Hunters have been blamed for this spread by transporting trapped hogs into new areas. I am sure this has happened, but I believe it due more to dog hunters than archers. Regardless, instead of using hunters to control the hogs many states have closed hogs to hunting while resource managers shoot them at night and from helicopters. They don’t want them listed as game species, just exotic vermin. Obviously few of them have eaten one.

Hogs in the South originally arrived with the Spanish explorers De Vaca in 1528 and Desoto in the mid 1540s. The Choctaw named Suganoochee Creek, or Hog Creek, in southwest Alabama long before the first European settlers came into the area. Later settlers lost free ranging hogs that mixed with the Spanish stock. A few European “Russians” were turned loose or escaped from hunt clubs, adding diversity.

Krista with a fat boar taken on St. Vincent NWR in Florida.

Downriver from Suganoochee in southwest Alabama, state properties provided the nest egg for restocking the eastern wild turkey in the United States. It was also the last refuge for whitetail deer in Alabama during the early 1900s. Somehow, in the 500 years since, they all seemed to coexist together making a hunter’s paradise, so to me the frantic fury to eradicate hogs is a little overblown. It is a moot point, for hogs are smart and prolific and the country too thick to ever eradicate them now. I have heard a lot of wild schemes concerning viruses and sterilization—just the type of experiment I surely don’t want conducted in the wild with the potential to wreak more havoc than the pigs themselves.

While populations are down in many areas, there is still good hunting to be found along the southern rivers. A more immediate concern to hunters is finding an area that is not a pine plantation so that actual stalking is possible. An ideal river bottom today will have at least a strip of hardwood timber in the bottom, probably with a pine plantation for bedding areas on the higher ground back from the river. The winter months can bring flooding, so that is a factor to consider.

The Mobile Delta management areas in southwest Alabama have good populations of hogs, and if you can reach the area when it isn’t flooded, parts are accessible by road on the east side. All of the rivers in north Florida have hogs, but you may have a hard time finding any hardwood timber left. Check out the Ochlocknee River and the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge south of Tallahassee. The St. Vincent Island NWR where Jungle Road is located can be good, but may alternate with lean periods following heavy management trapping efforts. My first hog came from along a South Georgia stream over forty years ago, and I’m sure that with a little research you can find huntable river bottoms there. I have also heard of good populations and hunting opportunities in central and western Mississippi.

It is necessary to study the hunting regulations. In some areas hogs may be hunted as small game after deer season closes in late winter, but illogically broadheads aren’t allowed. In spite of their desire to reduce hog numbers, few if any upper level state managers have gone out of their way to encourage hunting them. Local biologists are your best bet to help find good hunting.

The shield on a boar.

When a general area with hogs is located, spend a lot of time traveling by foot, boat, or truck depending on terrain, checking for fresh rooting or heavy trails. Once fresh sign is found start scouting on foot, trying to determine if hogs were just passing through or using the area. Hogs will return to the same food source, generally acorns, if undisturbed for a couple of days, but then may move miles. Just finding rooting or even lots of droppings and crumbled up acorns won’t guarantee a shot.

Hogs many times, especially on public land, won’t feed far from their bedding area during daylight. In other areas, they usually travel some distance on trails before spreading out to feed. I locate the trails with fresh feeding sign and quietly still-hunt into the wind, hopefully intercepting them. If not, I look for a potential bedding area of briars or thick grass where I can stand quietly and listen. Hogs are vocal, and I have actually slipped up on snoring bedded hogs in thick grass several times.

Sometimes when the wind is right, you can smell them before they smell you. There is never any use moving along a trail downwind. Find another area. Scent is everything. I never scout downwind. Hogs have superior noses and about as much curiosity about man as a wild turkey. One whiff and they are gone. Your scent will pool up and spread out close to the ground in humid swamps, and hogs can smell you even upwind. Their noses are inches from the ground when traveling, so it is important not to wander around scenting up the area. I don’t expect to see a hog over ground I have walked that day.

Once a sounder of small pigs that I am sure had never encountered man before was trotting up a riverbank. I had crossed their trail in rubber boots forty-five minutes earlier. Upon reaching that spot, they instantly bolted with a squeal and ran out of sight. You can’t fool a pig’s nose. Move cautiously, set up quietly near a trail leading from a thicket where you expect hogs, and stay until the end of legal hunting light. Often you will hear them come out behind you in the dark during the hike out, as if they were just waiting for you to leave. Expect to encounter them any time of day, and always be watchful and ready. If you do put them to bed, ease in before daylight and move very slowly, watching carefully for hogs out feeding until mid-morning. Sometimes they make a racket, and sometimes they are quiet as ghosts.

Unlike many game animals, the spine of a hog makes a sharp downturn before attaching to the skull. Aim low for best results.

After hundreds of blood trails and necropsies over the years, I learned why hogs have such a reputation for being hard to kill. They aren’t deer. Most of the hog’s vitals are forward between the front shoulders, and the backbone is much lower than expected out of the back of a flat skull and short neck. The spine is even with the jaw line, dipping down almost to mid-body at the shoulders. Hogs also stand closer to the ground than deer, and in cover you may only be seeing the top half. I never consider shooting behind the front shoulder unless it is an angling forward shot. I shoot for the front leg just above the leg knuckle and never shoot a hog facing forward or angling forward except in self-defense.

A single wounded hog may stop in the first thicket it reaches, but if running with others it will die on its feet. A double lung shot hog will go down more quickly than a whitetail, in my opinion, but get just one lung and it will disappear after a long blood trail. Shoot to get both lungs. The heart and lungs are beneath that shoulder, and not much is behind it. Hogs have big livers, and a liver shot will kill one quickly, but don’t depend on that shot placement. Shoot through the front leg with a heavy arrow.

That can be difficult, since they are seldom still and many can be darting all around. Don’t expect standing still shots. They trot along at a brisk clip and are very active while feeding. Forget about the infamous shield, which is only a problem for lightweight modern arrows and broadheads. You may not get an arrow to exit as the shield will slow it down, but the arrow should be buried in the off shoulder anyway. Shot through both shoulders, a hog is not going anywhere.

Remove the glands, like this one from the rear hindquarters.

Now for the good part! I wear rubber gloves while skinning them, although the only disease they carry that affects man is trichinosis. Cook the meat well. I keep a pot handy while skinning and trim the fat from the body and hide to cook down later for wonderful cooking and multi-purpose oil. Hogs have big glands on the forward edge of the back quarters in the loose skin leading down from the flank and in the center of the back of the hind legs in the crease of muscle above the leg joint. There is also a round gland on the inside of the front shoulders. The necks also contain glands. Cut out the glands to improve the quality of the meat.

My wife Krista also removes the “mountain oysters” from the boars and slices, soaks, and sautés them in the fat, but I try to be gone when she cooks them. The meat is a fine pinkish color, and meat from a fat, young hog will be quite tender. Leaner hogs can be tougher. Cooked very slowly over a pecan wood fire, an acorn-fattened ham is the finest meat on earth. I can’t think of any animal I would rather hunt.

Leave A Comment