“Everybody understood one thing in the mountains—that he must keep his life by his own courage and valor, or at the least by his own prudence.”—Joe Meek, Rocky Mountain Trapper, 1829

The lure of remote country is strong. As hunters, we long to explore off the beaten path, in search of a wilderness experience and animals that haven’t been pressured by others. But with every additional mile we put on our boots from the nearest road, we should never forget that our self-responsibility must increase as well. By thinking through the basics that need to be covered in the event of a backcountry emergency, it’s possible to be prepared with a kit that weighs little but will pay for itself many times over in the event it’s ever needed. In this article, we’ll look at what these basic factors are, and how to be prepared for their possibility.

Fire

It’s not enough to just have emergency gear in your pack – be thoroughly familiar with how to use it, before a desperate situation arises. Here, the author practices lighting a fire with a ferrocerium rod, or “firesteel.”

When you are in an emergency situation in the backcountry that requires a fire for warmth, don’t kid yourself—you need a fire right now. It’s great to know how to start a fire with a primitive striker and flint or a bow drill, but when you are already cold and wet with deteriorating manual dexterity and on the downward spiral toward hypothermia, this is no time to mess around with methods that take any more time than necessary.

I like having options when it comes to fire-starting gear, in case one doesn’t work. Inexpensive lighters can be useful, but keep in mind that lighters can fail, especially when wet. I keep mine in a small plastic bag so I know it will be dry when I need it. “Storm matches,” which are made to burn hotter and longer than regular kitchen matches, are another good option, although they must be kept dry as well. A ferrocerium rod, or “fire steel,” will create a shower of white-hot sparks even when wet, but it’s important that you practice with it before you truly need it. Some even carry a road flare in their backcountry emergency kit. This is also an excellent option that will get a fire going in just about any conditions.

I like to carry several tinder options with me, rather than assuming I’ll find dry tinder in a time of need. Cotton balls soaked in petroleum jelly light easily and will burn for several minutes. There are also commercial tinders such as “Wet Fire” that come in sealed packets and work great in wet weather. Jute twine soaked in candle wax also burns well. Pull the fibers apart, fluff it up into a “nest” and apply flame.

Shelter

The author testing out a SOL Emergency Bivy in sub-freezing conditions. It weighs a mere 3.8 ounces and provides better protection from the elements than a space blanket. In a real situation, creating a bed of pine boughs to lay on top of will create an additional insulating layer.

“Shelter” in an emergency situation means anything that will protect you from the elements. Depending on the situation, shelter in its most basic form could simply mean putting on the extra clothing you have with you and finding a place to tuck out of the wind, rain, or snow. Consider extra layers and rain gear as the basic cornerstone of your emergency shelter system, regardless of what other shelter solutions you may carry.

A small nylon tarp (5’x7’ is about the smallest useful size) is another consideration. Modern silnylon is a better choice than coated nylon for this application. The former is much lighter in weight and more packable, and a “solosize” silnylon tarp will take up little room in a daypack.

I carry a SOL Emergency Bivy as part of my kit. It packs up to about the size of a lemon, is waterproof, and provides much more effective coverage and heat retention than a space blanket. The SOL bivy’s bright orange color can also aid others searching for you.

Signaling

Let’s assume for the purposes of this article, that the definition of “backcountry” includes a lack of cell phone reception. There are other high-tech solutions available—a satellite phone, for example, or a “SPOT” device, which sends updates about your location to a pre-determined text or e-mail address. Neither of these options is a bad idea if you are in truly remote country, but wise woodsmen never put all their faith in a single solution, especially one dependent on batteries and other technology.

Low-tech signaling options fall into two categories—auditory and visual. An excellent choice for an inexpensive and lightweight auditory signal is a loud plastic whistle. Its sound can carry a good distance and is far more effective than mere yelling. A good option is the Fox 40 whistle, which doesn’t have a pea inside that can freeze and render a whistle useless in cold temperatures.

Examples of visual signals include a signal mirror, flashlight, headlamp, flares, smoke from a fire, and glow sticks. Even brightly colored fabric should be considered a “signaling” device, and a blaze orange hunting vest or bright flagging tape, which are often carried when hunting anyway, can help someone locate you. I have particularly come to like the military-grade glow sticks available at most surplus stores. They are inexpensive, lightweight, don’t require batteries, still function when wet, and can be seen for a long distance at night. I keep a couple of them stashed in my pack on all backcountry trips.

Water

In an extended emergency situation, water becomes critical. If you have exhausted whatever water supply you were carrying, you will need to find a water source. Try not to wait until you have no water left to start looking for more, if at all possible. Consider having a way to treat backcountry water. Boiling, filtration, and chemical treatment are all options.

Boiling obviously requires a fire or stove of some sort. But what sometimes gets overlooked is that you will also need something to boil water in, and for that you’re going to need an uncoated metal container. While a fire can be time-intensive, if you are in an emergency situation it’s probably not a bad idea to get a fire going anyway.

Water filters have come a long way from the bulky items they used to be. There are some very small and lightweight filters available now, with the Sawyer “Mini” and the “Lifestraw” being good emergency options that are easy to carry along. Both weigh a scant few ounces, are only a few inches long, and can be found for about $20. I own the Sawyer, and it works surprisingly well for such an inexpensive option. Chemical treatment is another effective, lightweight alternative. Iodine or chlorine dioxide are two popular options for water treatment. I personally like the Aquamira (chlorine dioxide) tablets that come in sealed packets. They weigh almost nothing, and do not have the aftertaste of iodine.

Another option is the SteriPen (or several other similar products), which sterilizes by sending UV light through a bottle of water. While they work quite well and don’t leave an aftertaste, they require a battery and weigh more than a packet of treatment tablets or the Sawyer Mini.

Dr. Don Thomas will cover this subject in more detail in a Backcountry column later this year.

Food

I never go into the backcountry without food in my pack. In addition to what I normally plan to eat for the day’s hunt, I bring a little reserve food just in case I’m out longer than planned. While water is much more important than food in emergency situations (the body starts to shut down from dehydration long before starvation), it’s not a bad idea to have an extra energy bar or two stashed in your pack. I also keep a couple of tea bags and a “Cup O Soup” packet in my emergency kit, and sometimes a dehydrated meal as well, just in case.

Other Considerations

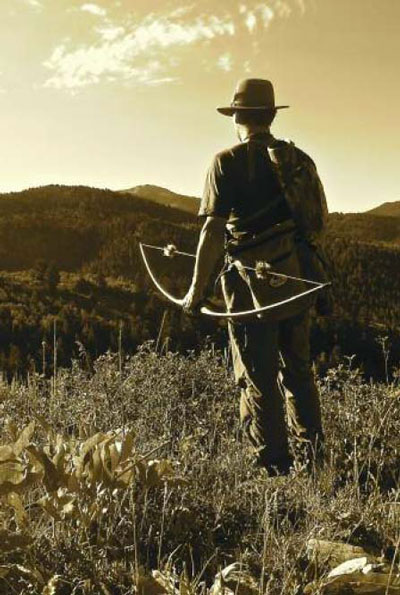

The lure of remote country is strong, but we should never forget that with each step in that direction, our self-sufficiency must increase as well.

First Aid Kit. In addition to my Emergency Kit, I always carry a first aid kit on my backcountry hunts. This is a broad enough topic for a separate article of it own, (and there will be one in this column within the year). Suffice to say this is another essential piece of emergency gear that you shouldn’t be without. Even more importantly, get the training to know how to use what’s in it. Knife. A stout, fixed blade knife is always on my belt in the backcountry. In addition to being essential for breaking down an animal, it is a versatile tool that can split wood, help construct shelter if necessary, and serve a number of other survival tasks.

Your personal emergency kit for the backcountry should never simply be replicated from someone else’s list. Only you can determine what your anticipated circumstances may require, and this article is only meant to provide food for thought. Just as you practice regularly with your bow, don’t simply run out and purchase emergency items, drop them in your pack, and assume you’re “good to go” if something happens. If you choose to carry an emergency blanket for example, wait for a cold rainy day and go spend several hours outside wrapped up in it, and then determine if it serves your needs. If you carry a firemaking implement, build fires with it in cold, wet conditions beforehand. It’s not just important to have gear for emergencies. It’s also essential to know that what you carry is truly going to work, based on firsthand, prior experience. Lastly, don’t forget the single most important piece of emergency gear—that grey matter between your ears. It can serve you well in avoiding many backcountry emergencies in the first place.

Top Photo: The author’s emergency kit includes a bivy sack, several options to make fire and treat water, quick-energy food, options for signaling help, as well as cordage and duct tape. It all fits in the compact titanium container on the left, which can also be used to boil water. Total kit weight: 1.5 lbs.

Our Facebook friend, Gary Britton posted the following to add to Bruce’s article.

Gary T. Britton You have 3 of the 5 essentials covered and what I teach in my MT Hunters Education survival class called Survival with Otzi the Iceman. Found on my youtube channel Big Sky Outdoorsman.

You covered fire very well but recommend that each hunter always carry 3 methods to start fire. A Bic Lighter which will be your go to method as it is the easiest. Remember to remove the child safety of the wheel…try using it with cold fingers and the safety in place. Second is a Ferrocium Rod which can create fire in any element and lastly a forever renewable source of fire…a 5x Magnifying Glass.

Second is shelter/cover…using the rule of 3…you can survive 3 minutes without oxygen and 3 hours before exposure sets in in inclement weather, 3 days without water and of course 3 weeks without food. The important thing to remember here is to get out of wind and rain which is the fastest way to worsen your situation.

Third you covered water and that also falls in our rule of 3’s. To do this it is highly recommended to carry a metal container of stainless steel, titanium, or even aluminum if that is all you can get. The metal is important for the ability to sterilize your water with fire and reducing the risk of sickness. Metal containers are also more durable and reduce the risk of breaking. Being able to drink warm water will also help reduce exposure of hypothermia much quicker.

While your other two areas are important and I am not belittling them…there are two items that are even more important because they are the hardest to create in a survival situation. 1. A full tang Cutting Tool. One that can not only help you clean your game if necessary but can get through to the inner dry wood of standing limbs and small dead trees. That knife can help you get your fire going much easier. A knife can also help you build that shelter a lot quicker and much more effective. 2. Cordage! Carrying para cord or tared bank line is more important then food which you can do without for 2-3 weeks. Cord will help you build your shelter, can be used for first aid, can be used to fix equipment or clothing, can be used for snares and fishing to get that food.

5,300 years ago, Otzi carried these 5 things with him plus his incomplete bow. He carried his small knife and other flint cutting items, he carried two birch bark containers of which one carried his smoldering embers to quickly start a fire but also carried flint and pyrite to spark a new fire (two methods to start a fire), he had cordage for repairing, his bow string and other strips of leather for various other uses, and he had a heavy hat and grass cloak for cover. So if Otzi carried these 5 items 5,300 years ago…why are our hunters of today, not carrying these same 5 items???

Gary T. Britton Sure hope that came across correctly as I did not want to come across as being negative. You actually have your signaling covered with your Bivy (I carry the Double Bivy bag) which is visual. The important thing to look for in your gear is that each item you carry be able to do three different things (again that number 3). So your bivy is a shelter, signaling device and can be used to gather leaves/needles for your bed to prevent convection. If you watch my video, you will see that my list goes beyond the first primary 5 items and the second set of 5 includes more important items while the final 5 includes the whistle you mention in your article.

My point in teaching the way I do is that instead of hunters/outdoors people carrying their phone and a bottle of water, and ending up a statistic to exposure or activating S&R that you can keep yourself safe for 72 hours with just 5 items and knowing how to use them. This keeps the weight minimal and still maintain the ability to keep yourself alive. The average rescue time once activated is 72 hours and if I can keep my students alive that long then the odds are pretty good and I did my job.