Most folks do not like to carry guns when bowhunting. However, bowhunters can get into situations where more lethal weaponry is desirable, especially when hunting in bear country.

The most common bear in North America is the black bear. While this species does not usually attack people, there are times when even they pose a threat. I found this out when two approached me very, very closely one day in the wilds of Alaska—ears up, noses twitching, casually walking right up to me. It certainly looked to me like they had dinner on their minds, and indeed most black bear attacks come from bears that want to eat people.

You can deploy bear spray in “battery” from a holster.

Nevertheless, most bear attacks on humans in Alaska are by brown bears (to biologists like me brown bear is the correct term for anything in North America that isn’t a black or polar bear, but for the sake of clarity I will refer to them here as the more familiar grizzly), and most of these attacks are defensive in nature, i.e. the bear was defending cubs, food, or personal space. Some bowhunters in Alaska and in the Intermountain West, where the grizzly population is increasing, respond to these threats by carrying handguns for bear protection. But are handguns the best option for defense against a large, charging mammal? Of course, it depends on the skill of the individual and the circumstances, but in most cases, I don’t think so, even if handguns are convenient to carry. In fact, during my bear safety training days, I tried to dissuade students from carrying handguns as a bear deterrent. Here is why:

Most bad bear encounters start when the human and the bear are very close together. This makes sense, as normally bears hightail it the other way when they see a person. Surprising a grizzly bear up close is when things can go gunny-sacks very quickly. Bears are really fast on their feet—faster than Usain Bolt. They can cover 30 yards in as little as two seconds once they get going! This means you only have a few seconds to stop a charging grizzly bear surprised at close quarters. In my experience, the average Joe can’t shoot a handgun accurately enough to do that. So, this is what I used to tell folks who were going into the Alaskan bush to do resource work and were attending my bear safety classes: “If you can run a mile (to amp up your heart rate like it will be during a charge), then, in two seconds pull your handgun out and hit a grapefruit swinging on a string ten yards away (which approximates a fatal shot on a moving bear) on the first shot, you are good enough to depend on a handgun as a bear deterrent. The rest of you, carry a pump shotgun loaded with slugs.” Why the first shot? Because the recoil of a large bore handgun is so violent that you may not be able to recover in time to get a second shot off at a fast moving bear. Consequently, the first shot had better be very, very good.

I have shot several big game animals with handgun calibers that are often carried for bear deterrence (e.g. .44 mag. and .454 Casull). The animals I shot with revolvers did not die quickly enough for me to consider carrying one as a primary bear deterrent. They were cases of “dead, just doesn’t know it, yet.” A fatally wounded grizzly bear can still cause a guy a lot of damage in the seconds before it dies.

If you find yourself among fresh bear sign, it’s best to carry your bear spray in the ready position, and deploy directly into the bear’s face.

Whether to use bear spray or a firearm as bear protection is a controversial subject, partly because bears, humans, and the events surrounding attacks on people are so variable—and rare. In my opinion, the best option is to carry both a shotgun loaded with slugs and bear spray while in bear country. “But shotguns are so heavy and cumbersome, and I don’t want to carry a gun, anyway!”, you say. Fortunately, there is mounting evidence that bear spray alone may be the solution for those who do not want to carry a firearm.

Two articles in the Journal of Wildlife Management, one of the most respected scientific journals on wildlife biology, have direct bearing on this discussion. Both dealt with bear/human interactions in Alaska. In the first, the authors provide evidence that bear spray is effective in deterring aggressive bears (Smith, Tom S., et al. 2008. “Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska.” The Journal of Wildlife Management , volume 72: 640-645.), and, in the second, that bear spray can be a more effective bear deterrent than a firearm (Smith, Tom S. et al. 2012.“Efficacy of Firearms for Bear Deterrence in Alaska.” The Journal of Wildlife Management, volume 76: 1021-1027).

Bear spray has several advantages for the bowhunter. First, a canister of bear spray is a lot lighter to pack around than a hand cannon of sufficient power to effectively stop a bear, lighter even than the newish, scandium revolvers (which, I have found to be even harder to shoot accurately than regular handguns!). Because bear spray is more convenient to carry, I think bowhunters are more likely to carry it consistently in the field. Second, even though you should practice with it before you take bear spray afield, it’s easy for most folks to get “on target,” because you can see the spray and adjust your aim immediately. Lastly, if you stop an aggressive bear with bear spray, the bear still lives, and you go on your merry way with a good story to tell. In contrast, if you shoot an aggressive bear with a firearm, the bad continues if you don’t have a bear tag, or it is not bear season. In Alaska, at least, you have to pack the hide and head out and turn them over to the State, and answer a lot of questions, too. At worst, someone might have to hunt down a brushed up, wounded bear, and that can be a dangerous, frightening affair.

Bear spray is easily obtained in most sporting goods stores. Each can comes with instructions. There is good information on its use on the Internet, too, so I won’t go into the mechanics of deploying it. However, I would like to make several key points about its use.

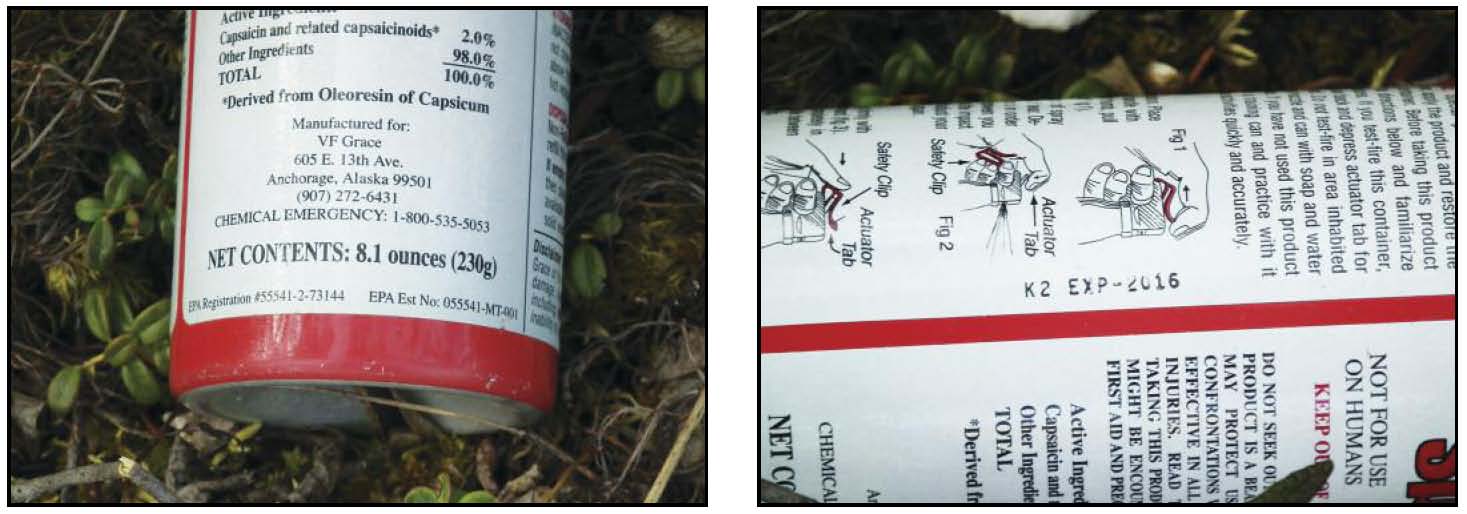

Do not be tempted to use that little can of personal defense spray on your key chain as a bear deterrent. It probably won’t work very well on a 600-pound grizzly barreling down on you. Only carry bear spray that is registered with the EPA as a bear deterrent. Each can that meets their criteria will have an EPA registration number printed on its label. That way you can be sure to have adequate volume, concentration of active ingredients, spray pattern, and reach for use as a bear deterrent.

You have to get the stuff in the bear’s face where it causes involuntary eye closure and severe coughing fits. Concentrate on getting it into their nose and eyes.

Carry bear spray where you can get at it quickly, e.g. on your hip, or on the chest or shoulder straps on your backpack.

Cans of “inert” spray are available. They are identical to real bear spray, but without its active ingredients. Bowhunters who plan on taking bear spray as a deterrent should buy some and practice before going hunting.

Practice. Cans of “inert” spray are available and cheaper than the real McCoy. They are replicas of real cans of bear spray, but without the “stinkum.” Buy some and practice getting the can out of its holster quickly, the safety wedge off, and shooting the stuff so you know how it works. Practice shooting it “in battery” without removing it from the holster so you have that experience just in case events move so fast you can’t extract the can from your holster in time. Remind yourself why you are carrying it—to protect your life. Practice makes perfect.

If you are hunting in cold weather but before bears have gone into hibernation, keep your bear spray warm by carrying it next to your body under your coat. Performance declines when cans are really cold. Carrying bear spray under your coat means you have to practice even more to get it out quickly.

Paradoxically, bear spray residue attracts bears. So, do not practice around camp, and wash off any used cans with soap and water before you put them in your backpack.

Carry two cans, one where it is readily accessible and one inside your pack. That way if you have to deploy your primary can, you have another to use as a deterrent for the rest of the day. Together, they still weigh less than a loaded firearm.

Most cans of bear spray are marked with an expiration date. Buy a new can when yours expires. Why? The cans leak a little pressure all the time. If you keep a can past its expiration date, it will have diminished performance. If you keep it around long enough, your can will have no performance at all. Then, what are you going to do when faced with a charging bear? Again, remember why you are carrying it—to protect your life. Use the old cans for practice.

Make sure you only carry spray cans with an EPA registration number, and replace by the expiration date.

Again, most bad bear incidents occur when someone surprises a grizzly bear that is very close by. So, if you have seen fresh sign (e.g. tracks or scat), you are approaching a food source (e.g. a salmon stream, or the quarters from the elk you killed that morning), it is a noisy place (like near a stream), the vegetation is thick you are walking into the wind, then I suggest you take your bear spray out and carry it in your hand, ready to deploy. When bears can’t see, hear, or smell you, and you blunder onto them up close, things can go south pretty fast. Be ready to get that spray in the bear’s face, pronto.

The length of time bear spray affects bears varies. If you have to deploy it, once the aggressive bear has stopped its behavior, leave the area immediately. Be expeditious and keep an eye on the bear, but do not run. You should never run from a bear.

People worry about deploying bear spray into the wind. The article I referenced above about its efficacy notes wind has not often been an issue in Alaska. However, if you cannot maneuver into an upwind position, here are some suggestions: 1) Get in the habit of taking and holding a deep breath just as you deploy bear spray. I do this even on calm days. The stuff sometimes wafts around in the woods and gets into your lungs. 2) If you are wearing a billed cap, tip your head down to shield your face from the blowback when aiming into the wind, 3) Quickly grab the neck of your shirt and pull it up to protect your face from blowback. In short, do what you can to get the spray into the eyes and lungs of the oncoming bear and not into yours. If all else fails and you do get a face full of bear spray, remember, you can hold your eye(s) open with your other hand and keep track of the bear while you spray it.

If you are sprayed with bear spray the effects are temporary, usually lasting 30-45 min. in humans. I have been sprayed in the face. It was an uncomfortable experience but I recovered in that timeframe. However, I will say they were unusually long minutes!

Carry a little vial of no more tears type shampoo so you can wash up if you do get bear spray in your eyes or on your hands (I once touched my eye with an unwashed hand hours after deploying bear spray and wound up frantically searching for soap and water to wash around my eyes).

When transporting cans of bear spray in a vehicle, carry them in cases designed for this purpose so the operator is not accidentally sprayed while en-route to your hunting area; remember that bear spray will cause involuntary eye closure! Note: the teeth marks on this case occurred when a bear found the author’s case hanging in a tree after he used it to transport bear spray to a remote lake on a fly-in hunt in Alaska.

Do not leave a can of bear spray in your vehicle on a hot day with the windows rolled up! Remember Chemistry 101: as you increase temperature in a closed system (like a can of bear spray), you increase pressure in the system. If enough pressure builds up in a can, it can explode!

Speaking of vehicles, buy a transportation container that has been designed for bear spray for each of your cans. Put them in it, upside down, when you transport the stuff in your vehicle. Remember that it causes involuntary eye closure. An accidental discharge in your vehicle while you are driving down the road is a potential disaster. Why upside down? The pickup tube inside the can runs from the dispensing valve down to the bottom. When you invert the can, the pickup tube is now above the actual level of the bear spray and it cannot be discharged.

In the end, the decision about what deterrent to carry is a personal one, because ultimately you are responsible for your own safety. So, study information on the subject, and make an informed decision about what to carry as protection when bowhunting in bear country. If you decide to use bear spray, maybe you can leave the “hog-leg” at home and still be “loaded for bear” next bow season. Be smart, stay safe.

Flying with Bear Spray

FAA regulations prohibit carrying bear spray on all commercial flights, including in checked baggage. This is the source of some confusion, since small amounts (less than 4 ounces) of pepper spray, as used in some “keychain” personal protection products, are permissible. Amounts large enough to be useful on bears are forbidden. This means you will have to acquire spray at the end of your last commercial flight, which can be a problem in some remote villages. Inquire in advance, and plan on using alternative means of protection (a firearm) if that is not possible.

No bush pilot I know will fly with bear spray inside the aircraft. If you are flying on floats, spray can be carried in a float compartment. If not, it can usually be taped to landing gear. The important point is to work this out well before takeoff to avoid last minute confusion or conflict.

Don Thomas

Leave A Comment