Perhaps the most enjoyable aspect of my long run as Co-editor of this magazine (and yes, I’m still deeply involved although not in that capacity) was working with our fine contributors, many of whom became friends. Some of them were established writers who consistently submitted well-written material on appropriate topics, making my job easy. Others were new to the process, and their material required either more work on my part or the aspect of the job that all editors hate: a rejection letter. Those were especially hard to write when a new contributor appeared enthusiastic and showed evidence of raw talent that just wasn’t yet ready for prime time.

Capture a unique image that tells a story. Include a description in the text.

I’ve been writing professionally for over 40 years now, and my bibliography includes 20-something books and nearly 2,000 feature articles and columns published in some two-dozen nationally distributed magazines. I’m not blowing my own horn (in fact, some of that writing really isn’t all that good), and I mention these numbers just to establish my credentials for giving the advice that follows.

The myth that successful writers consistently get their material published just because they “know somebody” is just that: a myth. Nothing makes an editor’s day like receiving an unsolicited piece from an unknown party and realizing that you’re looking at something really good and have perhaps discovered a new talent who might soon become one of your reliable contributors. I have enjoyed that experience with a number of folks who are now on TBM’s masthead. Furthermore, how do you suppose established writers got to “know somebody” in the first place? That privilege doesn’t come on a silver platter. It’s the result of hard work, good writing, and the ability to develop strong editorial relationships.

Lots of new writers ask for advice and guidance (as they should), and editors are frequently the recipients of such requests. Some routinely blow them off by sending out a form rejection letter or failing to reply at all. That’s understandable to some degree, since editors are busy people, and nothing requires them to spend time teaching beginners how to write. I can honestly say that I always tried to do better, although only our contributors can tell how successful those efforts were. I tried to respond promptly unless I was somewhere off the grid halfway around the world. When I had to write a rejection letter, I tried to offer at least a brief explanation for why I was writing it. When I saw raw talent coupled with enthusiasm, I made a real effort to be helpful.

One thing I have learned along the way is that a lot of hunters and anglers want to be writers, as demonstrated by the number of self-published books (of highly variable quality) now on the market. You are the people for whom I am writing this essay. I’m going to focus specifically upon the skill set required to publish consistently in magazines like this one. As much as we’d all like to write a great novel, starting on a smaller scale allows quicker feedback and a greater chance of finding a helpful editor. Besides, I don’t know how to write a novel. (I’ve tried.)

I rarely write in bullet-point format, a style that makes me feel like a salesman giving a presentation to a client. I’m breaking that rule here in the interest of expediency. In addition to the actual writing, a lot of what follows will deal with getting what you’ve written into print simply because I’ve been asked about that aspect of the process so frequently.

Don and Nebraska bowhunter Doug Otte review some basic traditional archery information to young Keegan Schultz in Zimbabwe. Teaching others is an honorable reason to write.

• Don’t succumb to lack of confidence. Although medical school was always my ultimate target destination, I received my undergraduate degree in English from a school whose English department was widely regarded as one of the best in the country. That process taught me a lot about Shakespeare (a lifelong source of joy) but next to nothing about writing. I had to learn that mostly on my own, by means we’ll discuss further as we go along. The point is that almost no one has it figured out from the start, so no matter how little you think you know, you’re not behind the pack.

• Write about topics you know and care about. This point may be a given here, since most of you reading this essay are interested in writing about the outdoors. If you want to branch out later, as I have done with nature writing and short fiction, well and good, but it’s best to start out with your feet on the ground in familiar territory.

• Decide who you’re writing for before you start to write. Say I’ve just returned from an interesting moose hunt that I think will make a good story. I’ll write it in very different ways depending on whether I plan to send it to Traditional Bowhunter, Bowhunter, Sports Afield, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Western Hunting Journal, or Alaska. To learn what different approaches work best for which publication, see below. I could always tell when an inexperienced writer had done a piece and sent the exact same text around to a dozen different publications. That’s a sure sign of an amateur and a quick route to a rejection letter.

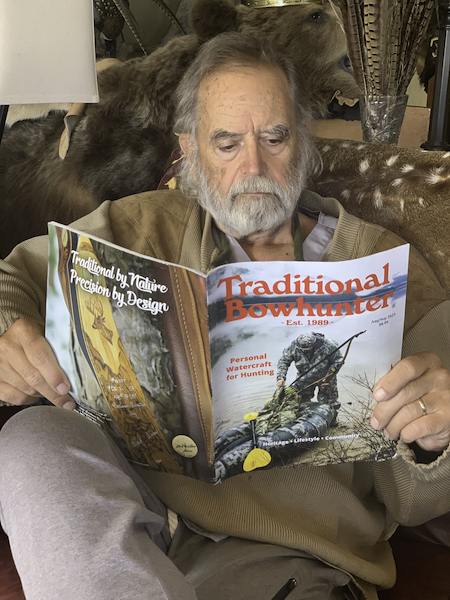

Read the magazine! It’s telling you what the editors are looking for.

• Read the magazine! This rule may seem simple and obvious, but new writers violate it frequently. Why else would anyone send this magazine an article about shooting an elk with a rifle? If you don’t have time to read three or four back issues of the magazine you’re submitting to you’re in the wrong business, and the editor will sniff that out quickly. The magazine is telling you what they’re looking for, in both style and content.

• Read the submission guidelines and follow them! Almost all magazines have a short segment on their website titled Contributor (or Submission) Guidelines. Read it carefully and do what it says. Ignoring these recommendations flagrantly is a good way to get your material to the bottom of the pile. Since ours state that we don’t run pieces longer than 3,000 words, why did I receive texts 6,000 words long? That wastes time on the writer’s part and leaves a bad impression on the editor.

• Define your goals from the start. Different people write for different reasons, and the choice is strictly up to you. However, that choice will influence many important decisions, from the way you write to how to you market it. Some people consider writing as an easy way to make some money. (Hint: It isn’t easy and there isn’t much money, unless you’re writing the next Harry Potter.) Others might be trying to build name recognition and become influencers on social media. (I’m not one of them.) Most of our contributors simply want to teach some of what they have learned, inspire others, help worthy causes, or recreate the atmosphere of storytelling around a campfire. Astute editors can tell the difference easily and generally prefer the latter.

• Don’t take rejection letters personally. Having material rejected is inevitable no matter who you are or how well you write. Magazines never have enough space to publish everything they receive, even when it’s good. Like a lot of writers in the outdoor field, I started out aiming high by submitting material to Gray’s Sporting Journal, which receives such a tremendous amount of good material that it’s the toughest nut in the field to crack. In the early 1980s, I could have papered the walls of my office with the rejection letters I received from them. Now I’m on the masthead and publish there regularly. What happened? Instead of pouting, I took an honest look at my work and realized that it just wasn’t good enough. Lots of careful thought and hard work eventually changed that, but it would have been easy to pretend that I was being treated unfairly (because I didn’t “know somebody”) and walk away. Every rejection letter should be viewed as a teaching moment.

Camaraderie is an important element of many hunting experiences. Don’t forget to write about it.

• Use your imagination. While editors (and readers) love material that is fresh and original, new writers tend to be timid and fall back on familiar formulas. How many ways are there to tell a story about shooting a whitetail with a bow? Not many, but being creative enough to find a new one will get your work to the top of the pile. The first piece I placed with this magazine was a story about having to shoot one of my lion hounds, right out of Old Yeller. Fortunately for me, T.J. saw something in it that he liked, and here we both are 30 years later. The usual cougar story runs along the lines of, “We found a track, the guide turned the dogs loose, we went to the tree, I shot it, and it was a big one.” This one was something else entirely, but it worked.

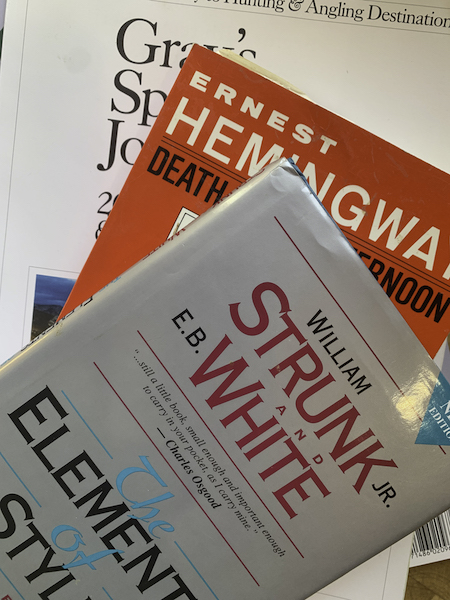

• Read others’ writing and analyze why you think it’s good or bad. We all have favorite writers, and we’ve also had the experience of starting a highly recommended book only to put it down after a couple of chapters and never look at it again. Judgement calls like that are personal and easy to make, but the novice writer should take the time to ask why and how? Why is Hemingway Hemingway and Faulkner Faulkner? How does the three-word opening line of Moby Dick motivate the reader to stick around for another 500 pages? Making yourself answer those questions will make you a better writer.

A photo can capture the mood of an African sunset, but words can too. Conveying the mood of a hunting experience helps the reader feel like part of the action.

Lori with a new fishing partner on an Alaska salmon stream. Describing brief moments of excitement provokes reader interest and adds life to the text.

• Don’t forget your camera. Years ago, when I first began writing for a trio of dog magazines including Retriever Journal (of which I am now Editor-at-Large), Steve Smith, who eventually became one of my favorite editors, gave me some career-saving advice. “Don,” he told me, “you are a terrific writer but your photography is terrible. If you’re going to succeed in this field, you need to learn how to take better pictures.” Competition from online publications has made cash scarce in the outdoor print market, and editors just don’t have the budget to shop around for file photos from other sources. I went to work on my photography and enjoyed it. Now Lori and I work as a team with even better results, according to others. Poor photo support was perhaps the most common reason I had to reject submissions to this magazine, even when the writing was good. Describing ways to improve your photography for publication is a topic for another day, but I can tell you that good technique and hard work are more important than expensive cameras.

Read writers whose work you admire and analyze the reasons you like it. Don’t forget Strunk and White!

• Purchase a copy of Strunk and White and read it until you know it by heart. Can a book about punctuation, English usage, and writing style really be enjoyable to read? In this case, the answer is not just yes but hell yes. First published by English professor William Strunk in 1918 and subsequently revised several times with major contributions from writer E. B. White, Elements of Style (usually referred to as Strunk and White) has become a standard reference that taught me more about writing in 100 pages than I learned in four years of college English.

Some readers will likely gloss over this piece to get to the bowhunting material that forms that heart of our publication. Fair enough—I won’t be offended. But given the number of readers who have asked me for help gaining entrance to the world of writing, I hope it will be useful and inspire some to become the new contributors we always welcome.

Don was fantastic at helping me get published and I’ve been blessed to have roughly 20 articles placed in national publications over the years. The writer with the best pictures wins and eliminate unnecessary words, were two of the great pieces of advice I received from Don.

Thank you Don, for your gracious and patient work with this neophyte writer.

Cheers!