When Kim Young found the envelopes from Colorado Parks and Wildlife in the mailbox, she casually took them inside to open them and endorse the $2,064 refund checks for unsuccessful nonresident moose applications. She and her husband Craig had both applied for the first time, holding virtually no hope of drawing one. But to increase their slim odds they decided to apply for different units to avoid competing with each other. It took a moment for Kim to realize that the item in the envelope was not a check, but instead a blue multi-fold stating “Nonresident antlerless moose.” She began jumping up and down and yelling for Craig. When Craig opened his envelope and discovered that he too had drawn a license, they thought perhaps a mistake had been made, or they were misreading the documents. But it proved true—they’d both drawn coveted Colorado nonresident cow moose tags!

Adding to the improbability was the fact that neither had ever seen a moose before, much less hunted one. They knew nothing of their habits or habitat. They both hunt with hybrid longbows and cedar arrows, so close shots were imperative. The task seemed so daunting that they discussed turning one license in to concentrate on trying to hunt just one of the beasts.

I was introduced to them by our local Wildlife Conservation Officer, who suggested I might offer some tips on where to start. I live high in the mountains on a moose drainage in the heart of Craig’s unit. I’m also a lifelong traditional archer and successful big game hunter with longbows and recurves, and fully understand the challenges presented by their equipment. Despite decades of applying I’ve never drawn a bull moose tag, but have helped several others scout and hunt in my unit. I have been chased by moose several times, had them eat my wife’s flowers by the porch and scratch their necks on our deck railing, and see them nearly every day from spring through fall. My WCO friend thought I’d enjoy some vicarious revenge after recently being charged by a crazed cow moose, chased down a mountain and through a creek, then hunted for nearly a half hour while I hid behind a fallen log, shivering in a snowdrift. Since that event, my affection for cow moose is limited to medium rare, with a side of roasted red potatoes and a glass of cabernet.

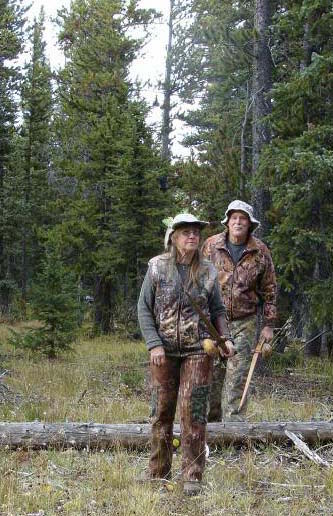

Kim and Craig are not only partners in life, but best hunting buddies as well.

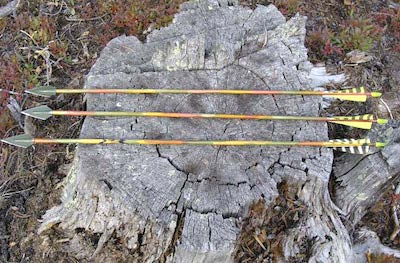

After talking with Craig on the phone for nearly two hours, it was apparent that these folks were serious traditional archers with high ethical standards. Craig had shot traditional bows since the age of nine, and has killed elk, deer, turkeys, and javelina. Kim is a relative newcomer to archery and bowhunting, but has killed deer, javelina, grouse, and quail. She was actually an anti-hunter before Craig pulled her into the sport fifteen years before. She tried some elk given to them by a friend, and flipped 180-degrees. Once hooked, she became an outstanding shot, filling their home with trophies and prizes won in 3-D shoots along with contributing to the freezer. Craig admits that she’s a better shot than he. They craft their own cedar arrows (“I love the smell when they break,” he told me…), fletching his hunting shafts with feathers from turkeys he and friends around the country have killed. Kim decorates her arrows with tiny hoof prints over her own camo design. They live on wild game they hunt and kill themselves, in multiple states each year. By trade they are fantastic stained glass and metal artists, considered among the very best in the U.S.

Before meeting up in Colorado to scout, Craig advised they would consider their hunt a success if they just saw a moose. I assured them they’d see plenty—although I’ve helped others on hunts where the moose simply disappeared when the season started. But that mostly happens later, during the rut, when they take to the high ridges and deep timber. During archery season they are usually around in the same drainages where they summer. On our first scouting trip we saw several cow moose, ranging from big old “elephant cows” to yearlings. I explained that the ones they wanted to shoot were A) medium-sized, B) reasonably close to a road, and C) not standing belly-deep in a swamp. Once they saw a few at close range and grasped their size, they readily agreed with that advice.

Since their tags were for different but adjacent units, we decided to focus first on my home area because of the overall number of moose and variety of habitat. We hoped to get Craig’s cow first, then they could spend the rest of the hunt in a less-accessible section of Kim’s unit.

Kim decorates her arrows with her own camo pattern, punctuated with tiny deer hoof prints.

Moose camp was on a high plateau at roughly 10,000 feet, with broad willow parks threading through dense stands of spruce and lodgepole. The most efficient method of hunting is to drive and glass, covering miles, until a moose is spotted. The challenge then becomes stalking within twenty-five yards of one feeding in an open willow meadow, in shifting wind. Some of these meadows are several hundred yards wide, with only knee-high willow cover. Others have willows over ten feet tall, where moose can literally disappear. An additional obstacle was the unfortunate circumstance of muzzleloader elk, deer, and moose season starting on the same day as archery moose, along with the archery deer, elk, and bear, and rifle bear seasons in progress. Grouse season was also on, and the area is popular with recreational OHV riders too.

Usually archery moose begins a week before muzzleloaders hit the woods, but that year a strange scheduling quirk crammed everybody into a big blender at the same time. Throughout the day before the season and on opening day, a steady parade of orange and camo-clad hunters in trucks, ATVs, and side-by-sides rumbled past camp. It was like an anthill of activity. During the summer the moose tend to vaporize when the weekend warriors hit the woods in their ATVs, reappearing during the week when things quiet-down. With this cacophony of constant mechanical mayhem buzzing in every direction, I reassured them that while we may not see anything for a day or two, the moose would reappear after the masses left. Privately, I was concerned because of the addition of the muzzleloaders to this stew—highly mobile hunters who wouldn’t be going home on Sunday.

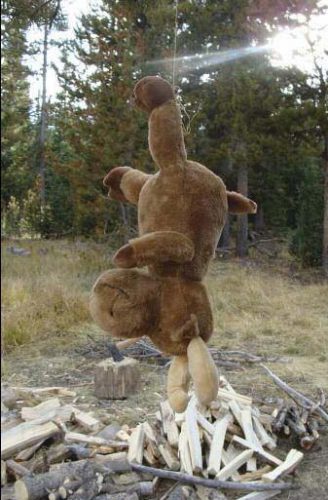

Good luck stuffed moose! Kim brought this stuffed moose to camp as a good luck talisman.

The first day of hunting in several different drainages produced only encounters with one decent bull, hordes of other hunters noisily camped at the edges of the best moose feeding parks, and no cows. On the second morning they took the hunt a few miles away from the ATV maze. Approaching a long, angled willow draw below some steep switchbacks, Kim joked that she bet they’d see a moose there. As they passed the meadow opening, Kim exclaimed, “There’s one!” Craig thought she was still joking. “No really, I just saw a cow back there!”

They drove on, parked around the corner, and Craig took off with his bow, working through a dense wall of timber and deadfall on the downwind side of the park. He carefully sneaked around the edge but couldn’t find her. The cow was gone. Craig started trudging back to the truck and then spotted ears poking above the willows where the cow and a calf were feeding in a low swale. We’d discussed the ethics of shooting a cow with a calf, but the biologist assured them that moose calves are born early, and if orphaned will quickly hook-up with other moose and be just fine.

Craig repositioned with the wind and began his stalk again. Kim watched the stalk unfold, and as he drew closer she instinctively decided to help him out by doing the “tourist thing” of making herself visible to distract the cow. They’re used to people stopping to photograph them and aren’t alarmed unless approached. Sure enough, the cow watched Kim on the county road, which allowed Craig to slip through the timber to within twenty yards. With the moose still looking away, Craig drove the cedar shaft through her on a quartering-away shot, and she collapsed in the meadow after stumbling only fifty yards. His arrow achieved full penetration after breaking a rib on both sides, and only his turkey fletches remained inside the cavity. The moose died within 150 yards of the road, making our packing job more of a joy than an ordeal.

Craig’s cow tipped over in a great place to process and pack out.

That night we dined on a super dinner of Craig’s “industrial lasagna,” retold the story of the stalk several times, and shared a campfire with our camp neighbor from Alaska, Ken Wolter, a traditional bowhunter who had a bull moose tag for the same area. It was a happy camp of bowhunters sitting beside the firelight that night, with shadows flickering off the stuffed game bags cooling on logs behind us. The scene represented everything good about hunters and the hunt.

The next morning Craig and I drove the meat down to Fort Collins to hang in a cooler and check his head in at the Parks and Wildlife office. The cow was wearing a radio collar, and the biologist who’d tagged her happened to be there. He explained how the collar was rigged with a .22 caliber blank, and when the battery on the transmitter began running low it would explode and release the collar for recovery. When it stopped moving for a few days they assumed she’d either been killed or it dropped off, and would search it out. They promised to send Craig a matrix showing where she was collared and her subsequent travels.

The following afternoon Craig and Kim relocated a couple of hours over the mountain to Kim’s unit. I planned to hunt elk for a day or two in a spot where I’d found a good bull before taking my camp over to join them, since my elk tag wasn’t valid in Kim’s moose unit. They’d scouted a likely spot suggested by the biologist earlier in the summer, and again the week before. It was an out-of-the way drainage near the Wyoming border that was overlooked by other moose hunters who concentrated on the more popular and accessible State Park in the heart of the unit.

Arriving there, they met a camp of elk hunters who suggested a finger drainage where they’d seen some moose earlier. The following morning they hiked into the drainage and had to avoid a surly-looking bull moose at sixty yards. Craig fell into a mud hole up to his waist, which held him so securely that Kim had to brace herself to pull him out. After that mishap they started back to the truck, but spotted fresh cow and calf moose tracks on the dirt road. With Craig still soaked and covered in mud, they began slowly following the tracks through the timber until they spotted the cow bedded at sixty yards.

Craig stayed back while Kim stalked the cow, using two tiny lodgepoles as blocking cover and taking forty-five minutes to close the distance to eighteen yards. Craig distracted the animal by raking a tree, and when the cow stood Kim crouched to shoot beneath a branch. The arrow drove through both lungs, and the moose fell over in seconds.

A perfect shot on Kim’s cow led to a quick recovery.

Kim was dumbstruck, since she’d never killed anything bigger than a deer before. She told me privately before that she doubted her ability to close the deal on a moose and wasn’t sure she was a good enough hunter or that her equipment would do the job. I reassured her that her equipment was fine, and I could tell by her genuine dedication and determination that her doubts weren’t warranted. She proved me correct.

The pack to the truck was less than a quarter-mile. While quartering the cow, a terrific windstorm arrived ahead of a cold front, blowing beetle-killed trees over all around them. Craig had to cantilever logs against a leaning tree to keep it from dropping onto the couple as they worked. And when I say “they,” I mean both of them, as little Kim was as involved in the skinning, butchering, and packing as Craig. I was packing up my camp to meet them when I received the excited cell message from Kim that they were finished and headed back to New Mexico with a massive load of tasty moose meat after less than thirty-six hours of hunting and meat packing.

Kim and Craig truly are soul-mates, partners in life, in their art, and in their hunting. That they each got to witness the other’s stalk and kill and then participate in the final processes of the hunt was an added gift for this wonderful couple. They later told me it was the most awesome hunting experience of their lives.

Lightning struck the first time when fate brought these two together thirty-seven years ago. It struck again when their unexpected licenses arrived in the mail. Then to have it all culminate in such a perfect hunt provided a fairy tale ending to an improbable chain of events, the epitome of an ethical, well-executed traditional bowhunt for big game. After getting to know Kim and Craig Young, I know no one deserves it more than them. They earned it. I am lucky to have met them, fortunate to have had the opportunity to help in a small way, and looking forward to future adventures with them.

I have no doubt that good things will continue to happen to these two great hunters and life partners. Their hunting fortunes are just beginning.

Equipment Notes: Craig’s bow is a Thunder Mountain R/D hybrid drawing 55#. His turkey-fletched cedar shafts are tipped with 140-grain Eclipse broadheads, plus a 20-grain added weight for increased FOC. Kim’s Thunder Mountain hybrid is 54# @ 28”, but at her 26.5” draw it’s just under 50#. Her cedar shafts and 125-grain Zwickeys weigh a total of 450 grains. The website for their art work is www.etsy.com/shop/ZuniMountainArtGlass.

Colorado’s Moose Story

Prior to 1978, Shiras moose in Colorado were limited to occasional transients from Utah and Wyoming. Then twenty-four were transplanted to North Park that spring. Additional moose from Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado’s own growing population were introduced to other areas of the state over the years. The moose Kim and Craig hunted originated from a transplant of twelve moose into the Laramie River valley in 1987.

By 2012, the reintroduction program had established a breeding population of more than 2,300 moose in Colorado. Moose hunting is available in 39 game management units (GMUs). There were 16,500 applicants for 219 moose hunting licenses and 185 moose were harvested in 2012. With such a high success rate, all hunters draw from the same pool, and are permitted to change weapons and seasons before each season begins. While the moose population in other states has declined, Colorado’s moose population continues to grow.

Leave A Comment