I only needed to make another 20 feet before I should be able to see where the goat had gone. I was scrambling to gain my footing on the steep scree when a grapefruit-sized rock slammed into my shoulder, almost knocking me down the slope and over a ledge. He must be heading up the cliff, I thought as I gained my footing and climbed the loose rock with my bow in my left hand and my finger tabs in my right. Rugged rock tore at my fingers as I climbed. When I reached my arrow lying where the billy had been bedded only moments before, I looked to my left and couldn’t believe my eyes. The last three and a half months suddenly felt like a dream.

The results of Montana’s drawing for 2015 moose, sheep, and goat tags were supposed to come out on Monday, June 15th. Early that day, I checked the Montana FWP website, but I must have been a little too early. Two more attempts found the website down. Busy with work Tuesday morning, I had no desire to see the all too familiar “Not Successful” icon on the draw results page. But when I checked later that morning, I saw: Successful, 2015 Goat License! Maybe some of you are used to seeing those simple words, but for me they have been a rarity! Thus began an epic journey to fulfill my lifelong dream to hunt the white dwellers of the high country.

I immediately dug out maps of the area and reviewed work and family schedules. I searched through my collection of Traditional Bowhunter and re-read every mountain goat article I could find. I planned the first scouting trip into the rugged goat country of my unit for the second weekend of July. I did not know it then, but this was to be the only trip I would be able to make into the area before the season began.

Friday July 10th found me leaving work as early as possible, to make the three-hour drive. My good friend and fellow high country addict, Arlis, was along for the fun. As we headed off the pavement and into the mountains, we were greeted with ominous dark clouds that quickly turned into an impressive summer rainstorm. A long muddy drive ended at the trailhead, where we found several other vehicles. Too anxious to get started, we decided not to wait for the rain to subside. We made just over five miles before we realized that we needed to make camp before dark. From the first clearing in the timber that allowed a view of the distant peaks, my first glassing scan located seven goats on a daunting cliff.

The next morning, we woke up early and headed in the remaining six miles to where we had last seen the goats. The entire way I just could not believe the beautiful high country, the copious number of summer wildflowers, and the thought that we should probably have horses, as every lush mountain meadow aroused anticipation of big bull elk. By the time the first scouting trip had ended we had spotted 32 goats, with 22 in a single band, and one big mule deer buck.

The author and his brother Tim on their first extended hunt in years.

A crazy work schedule did not allow for any additional trips before the September opener. My brother would be traveling up from Nevada to spend the week with me, “looking out for his little brother.” We hit the trail the day before the opener and backpacked ten miles into the area I had identified as a good base camp back in July. The combination of exhaustion from the hike and anticipation of actually being able to hunt mountain goats made sleep difficult.

At first light, I headed up the last half mile of mountain to start glassing the basins beyond. It didn’t take long to locate a band of nine goats that looked like billies some five miles distant. Climbing farther into the basin, I soon spotted six more goats in a drainage forming the boundary of my unit. A beautiful high mountain lake with a waterfall at its outlet added to the splendor of our surroundings. By the end of the first day, we had spotted six more goats, which looked to me, the amateur goat hunter, to be nannies, kids, and young billies. Not bad for my first ever day of goat hunting! That night back at camp, I began to feel the exhaustion from the last two days’ effort.

The next morning, we committed to go farther and get closer for a better look at the large band of goats I had spotted earlier. As soon as we topped the first ridgeline we quickly spotted the large group of goats, this time one drainage closer and with even more goats in tow. At first glance it appeared there might be close to 20 of them. We quickly decided to head closer for a better look.

The rock formations and high mountain basins were simply amazing. It was hard not to put a stalk on the large mule deer buck I had spotted at first light. My brother had to remind me to stay focused, and reminded me that, “We don’t want to pack a deer out of here too!” At the rim of the next side drainage my brother pointed out seven more goats in some of the steepest terrain imaginable, but they were closer than the big band. We could see two young billies in the group, but could not figure out a route through the cliffs. The larger of the two seemed to stand as a sentinel on a small ledge with only enough room for a sure-footed goat.

Determined to make it to the top of the mountain dividing two major basins, we set off for the top with a planned route to get closer to the large group of goats. It wasn’t long before we noticed a lone billy tucked up under a large cliff. My immediate thoughts were that he didn’t look like the biggest billy we’d seen, and that there was no way to get through those cliffs for a shot! After examining him from two vantage points, we decided that I should at least get closer and see if I could identify any possible route for a stalk. Throughout the hike we kept thinking we were about to be “cliffed-out” only to find decent goat trails through the slides and chutes. My brother would stay back and attempt to give me hand signals from a distance. We failed miserably in that department. I guess I should have paid more attention to past articles by Marv Clyncke.

This nanny and her two kids provided stalking practice.

As I crossed a creek to the other side of the basin, I stopped midstream when I spotted a goat not 80 yards distant. I could tell it was a large nanny, but thought I’d better take advantage of a perfect route to get closer in case there was a billy with her. Carefully navigating the stream bottom until I was out of sight and then looping around a small patch of timber, I came out just 20 yards from the bedded nanny with two white puffball kids lying beside her. After a quick picture as she began to stand, I was backtracking to get back on the trail of the billy.

My first attempt at an access route put me directly above the billy, looking straight down as he stood to stretch at the base of the cliff. Peering out over the ledge to view the goat and snap a picture sent a chilling sensation through my system that told me I’d gone far enough. This meant that I would have to circle wide beyond the bedded goat in search of a route down through the cliffs and then circle below and back up to the goat.

I still consider myself pretty young and agile, and I’m pretty confident in my mountain climbing abilities. But I have to admit that I don’t remember a time in my life that I have questioned my judgment as much as I did while descending that steep hillside, sliding on my backside through grassy spots, lowering myself and my bow over ledges, praying that the branches I was holding onto wouldn’t give way, and flat out wondering what I was doing there. Not long into the stalk, I knew that I was not going to be able to turn around and go back up the way I came. At one point as I stutter-stepped near one ledge after hopping off another one, I couldn’t help but wonder what it would be like to fall to my death with by brother filming me from a distance.

Finally reaching a spot where I knew I was within striking distance, I was disappointed to find one last crevasse separating me from the sleeping goat. It is amazing how different things look from a distance. A million things went through my mind, as I just didn’t know what move to make next. I didn’t even know if the goat was still there. The only route I could see was to go directly below the goat, through the crevasse and then up the scree, but I knew he would hear me. Finally, I decided I had to try. After all, even though I had no idea what my brother’s attempts at hand signals meant, he was still sitting there watching me.

As rocks rolled, I cringed thinking the goat would burst out of his hiding place at any moment. It was impossible to navigate the steep incline, which was covered with slick bear grass and loose scree, without making some noise. The high winds were my only saving grace. I nocked an arrow as I rounded the final ledge on the slim chance that the goat would still be there. Catching a glimpse of snowy white, I quickly tried to gain some footing in the loose rock and started drawing as the goat came to his feet. Another dreamlike moment unfolded as I came to full draw and watched the animal start to turn away.

The author’s arrow in flight, heading to the conclusion of a lifelong dream to take a mountain goat with his bow.

I thought the arrow was perfect until it made a loud crack against the cliff behind the goat and bounced back into his now vacant bed. Instinctively, a second arrow was on the string. As I was trying to pick a spot, I saw a crimson spot forming on the billy right behind the shoulder. At this point there was no turning back on the second arrow, and I watched it sail inches over the goat, followed by an incredible mountain goat half pipe scramble around the ledge and out of sight.

Standing near the arrow in the abandoned goat bed, a third arrow was hitting my string as I spotted the goat perched on a ledge 20 yards up the cliff from me. This time only the rock face immediately behind the goat prevented a complete pass-through. Time stopped as I experienced the realization that I had fulfilled a lifelong dream, while standing eye to eye with a majestic animal with a consuming feeling of respect and reverence for a life given.

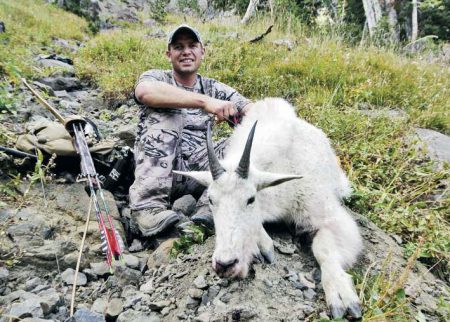

Years of dreaming came to fruition for the author with the taking of this beautiful billy.

Then the billy gave the one last kick that mountain goats are so well known for, which sent him head over heels down the ledges and past me by less than ten steps before coming to rest some 75 yards below. Words cannot describe the feeling of approaching the dead billy. All I could do was say a quick prayer of gratitude, with the inclusion of a plea for help finding a path back to my pack and my brother.

What an amazing experience to share with him. It had been fifteen years since we last spent this much time together in the backcountry. Time in the woods with brothers gets hard to come by with work schedules and growing families. As if it couldn’t become more of an adventure with over five miles back to camp and another ten to the trailhead, the following morning we were greeted by a large grizzly less than 80 yards from camp as we were packing to head home. My brother was just outside camp when I saw the bear. When we regrouped, I was explaining how I had jumped the large downed tree nearby in hopes of catching a picture of the bruin. Then my brother pointed out that I had jumped over the tree where we had left the bear spray, pistol, and rifle, all in hopes of getting a picture with my cell phone. Since moving to Montana nine years earlier, spotting a grizzly in the wild had been another one of my dreams. I must admit that I was hoping it would be from a little more distance.

Equipment Notes: On this hunt, the author carried a 58” 60# Thunderhorn 3-piece takedown by Duane Jessop, Carbon Express Pile Driver 250 shafts with 100-gr. brass inserts, and 125-gr. Magnus two-blade broadheads.

Leave A Comment